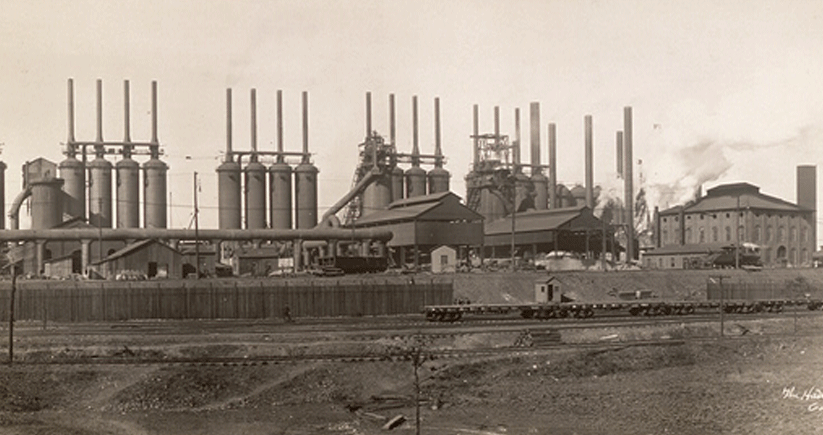

The Ensley Works operated between 1888 and 1976 and became part of U.S. Steel in 1907. For years, it was the largest steel producer in the Southeast. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress Photographic Archives

The Ensley Works operated between 1888 and 1976 and became part of U.S. Steel in 1907. For years, it was the largest steel producer in the Southeast. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress Photographic ArchivesEditor's note: This is the first story in a series exploring the economic histories of the largest metropolitan areas in the Southeast.

Alabama's largest city is enjoying something of a renaissance. A couple blocks from Birmingham's Railroad Park, a seven-year-old downtown jewel, sleek condominiums rise alongside the new home of the Birmingham Barons minor league baseball team. Scattered throughout town, trendy restaurants and galleries have earned plaudits from the likes of the New York Times and Garden & Gun magazine.

But like most American cities, Birmingham's economic energy flows only so far. West of downtown lie sagging old mill villages. Most striking is the abandoned Ensley works: century-old brick buildings and a half-dozen smokestacks stand above the woods that in 33 years have all but swallowed a factory that once employed thousands.

Big urban-suburban differences

Birmingham is prosperous in many ways. It's home to the touted University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) medical research complex and a clutch of regional banks. It boasts some of the South's wealthiest suburbs. Mountain Brook's median household income, $126,500, is the highest of any city in the Southeast with more than 10,000 people, according to U.S. Census Bureau statistics.

At the same time, Birmingham encompasses block after block of commercial and residential areas as desolate as the abandoned Ensley works. Although it might be an imperfect comparison, an economic gulf separates a couple of suburbs and the city of Birmingham. The city's median household income, for example, is a quarter of Mountain Brook's and roughly a third that of Vestavia Hills. Among city residents under 65, 18.5 percent lack health insurance—50 percent more than the ratio statewide, and greater than nine times the ratio in Mountain Brook and four times the rate in Vestavia Hills, according to census data.

Because of its rapid growth in the early 20th century, Birmingham became known as "the Magic City." Courtesy of the Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark

Because of its rapid growth in the early 20th century, Birmingham became known as "the Magic City." Courtesy of the Sloss Furnaces National Historic LandmarkPopulous, affluent suburbs are hardly unique to Birmingham, of course. Most metros—especially those in the Sun Belt that have grown dramatically in recent decades—have heavily suburban populations. The city of Atlanta, in fact, accounts for a smaller share of its (albeit far larger) metro population than does the city of Birmingham. However, the city of Atlanta's population is growing—by over 10 percent between 2010 and 2015, compared to 0.1 percent for the city of Birmingham. City populations in New Orleans, Jacksonville, Nashville, and Memphis have all grown more than Birmingham's in that five-year period.

Birmingham in many ways is typical in a country of widening economic disparities. In other ways, the town whose rapid growth earned it the nickname Magic City has an economic and cultural heritage that distinguishes it from other urban areas. Even though it's a youngster—Mobile and New Orleans were over 150 years old when Birmingham was founded in 1871—Birmingham and its economy nonetheless have been molded by an eventful, and sometimes tragic, past.

Birmingham sits astride a rare mineral bounty

Start at the city's beginnings. Birmingham sits in the Jones Valley, one of few places in the world harboring all three ingredients needed to make iron and steel: coal, limestone, and iron ore.

Birmingham began life as "workshop town" devoted to extracting and refining minerals. The town's first building, according to an early chronicler, Ethel Armes, was a blacksmith shop. It was born as essentially a colony of mine and mill owners, their workers, and workers' families. The companies built villages, with houses, schools, mail service, hospitals and town baseball teams. Pioneering entrepreneurs with names including DeBardeleben, Sloss, Ensley, and Powell made early 20th century Birmingham the South's foremost industrial hub.

Early promoters predicted it would rise to the top rank of the world's factory towns. In the 1880s and '90s, speculators bid up land prices from $10 an acre to $500 to $1,000 an acre, according to Armes's 1910 book, The Story of Coal and Iron in Alabama.

The area indeed flourished. Sharecroppers from the countryside and European immigrants flocked to the area to mine coal and do dangerous and taxing work in the furnaces. In the early decades of the 20th century, the Birmingham area's population grew much faster than those of other southern cities (see the chart). The city's population expanded from 3,000 in 1880 to 260,000 by 1930, which is larger than the city's—though not the metro area's—current population. In 1930, Birmingham's metropolitan area population nearly equaled that of Atlanta, its rival 145 miles to the east.

Yet labor relations were notoriously difficult. Industrialists suppressed organizing efforts, at times violently, throughout the early to mid-20th century. Widespread crime and several well-documented episodes of violence contributed to a Wild West reputation.

The iron and steel companies gave birth to Birmingham, creating tens of thousands of jobs and an aristocracy of owners and managers. But the power brokers behind the iron and steel firms largely kept Birmingham a one-industry town.

Dependence on the city's founding industry left the city vulnerable to economic swings. (As recently as the 1960s, U.S. Steel alone employed more than 40,000 people in the Birmingham area.) Indeed, the Hoover administration labeled Birmingham the nation's hardest-hit city during the Great Depression.

Amid the darkest hours, more positive forces gathered

The foundries and mills sparked back to life during World War II's military buildup. After the war, Birmingham's fortunes skidded anew as the steel industry slumped in the 1950s. At the same time, the darkest chapter in the city's history began to unfold. Even before the tragic church bombing that killed four girls in 1963, "Birmingham's race relations were widely considered the worst in the nation," Stanford economic historian Gavin Wright writes in his 2013 book, Sharing the Prize, The Economics of the Civil Rights Revolution in the American South.

Through the 1950s and '60s, a tug-of-war over racial policies played out between two camps of business elites. On one side were the industrialists, and on the other were more moderate factions of retailers, real estate developers, leaders of the burgeoning medical complex, and other professionals. This splintering of business interests would weaken industry recruitment efforts and warp the business community's response to civil rights upheaval, history shows.

Yet Birmingham became an international symbol of resistance to civil rights in part because boycotts and protests did not damage the city's iron and steel interests.

Birmingham's Civil Rights Institute and the new Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument commemorate the bloody struggles in the city led mainly by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. (statue pictured) and the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth. Photo by Kendrick Disch

Birmingham's Civil Rights Institute and the new Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument commemorate the bloody struggles in the city led mainly by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. (statue pictured) and the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth. Photo by Kendrick DischBecause the iron and steel interests—directed not just by locals but also by more distant executives and investors in northern cities—were mostly unconcerned about attracting new industry to Birmingham, they had little reason to fear the negative publicity that would subsequently scare away investment, concluded scholars such as Joseph Luders of Yeshiva University and Numan Bartley, an emeritus professor of history at the University of Georgia. However, downtown merchants were quite concerned. Protests and police repression of protestors, Luders writes, cost downtown Birmingham retailers estimated weekly losses equivalent to $6 million in today's money.

Yet even as Birmingham's grimmest chapter unfolded in the early 1960s, a more positive economic force was gathering strength. UAB was established in the 1940s as a medical school for the University of Alabama's main campus in Tuscaloosa. The Birmingham campus struggled for funding from the start and ultimately relied heavily on federal dollars. During the 1970s, no other medical school in the country received a larger portion of its funding from federal sources.

It paid off. By 1992, according to historian Charles Scribner and his 2002 book Renewing Birmingham: Federal Funding and the Power of Change 1929-1979, UAB was responsible, directly or indirectly, for every seventh job in the Birmingham metro area. The medical complex's influence, he writes, was "powerful testament to the transformative power of the health sciences complex—largely shaped by federal aid—and the ascendancy of the postindustrial service economy in the erstwhile iron and steel town."

History Matters. A Lot.

The Federal Reserve concerns itself mainly with the current and future state of the economy. Yet no clear understanding of the present is possible without an appreciation of the past.

With that principle in mind, William Roberds, a research economist and senior adviser at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, is organizing the Atlanta Fed's May 15–17 workshop on monetary and financial history.

The workshop will feature a keynote address by 2011 Nobel Prize winner Thomas J. Sargent. An economics professor at New York University, Sargent is scheduled to discuss the history of U.S. fiscal policy and how this relates to today's fiscal policy challenges.

A century of transition

In the Southeast and beyond, a vital function of historical knowledge is to place present circumstances into broader perspective. "The number one thing you learn from looking at economic history," Roberds says, "is how much better off we are today than 99 percent of people were in the distant past."

Will Roberds

Indeed, the history of the southeastern economy centers on an inexorable transformation to higher standards of living, Roberds says. Since the Atlanta Fed's founding in 1914, the overarching story concerns the regional economy's gradual evolution from an agrarian system based on a single commodity—cotton—to a more prosperous, diverse economy.

Historically, the Southeast was woefully poor compared with the rest of the nation. In 1930, only three states in the Atlanta Fed's district recorded per capita personal income of even half the national level, according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. (The Sixth Federal Reserve District includes all or parts of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee.) Regional incomes have since improved dramatically (see the chart).

Likewise, the region is far healthier. From the early 1800s until the mid-20th century, diseases such as hookworm, malaria, pellagra, and yellow fever plagued the South. In fact, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was established in Atlanta because the South, with its warm climate, was the area of the country with the most malaria transmission. Today all four of these diseases are all but eradicated in the United States.

Today's Birmingham a different place

Birmingham today is a different place from the national pariah of the 1960s. Much of the civil rights battleground is a 36-acre national monument established by President Barack Obama in January 2017. The Civil Rights Institute, near the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, is among the nation's foremost attractions devoted to African Americans' struggle for equality. Stanford's Wright also points out that in recent years Birmingham has generated more middle-class and professional employment among African Americans than Charlotte, relative to city size.

The Birmingham-Hoover metro area's employment base today boasts a bigger concentration of jobs in financial activities than New York, Charlotte, or Atlanta, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Birmingham's 43,000 financial jobs pay more than the national average. A downtown incubator affiliated with UAB houses 102 startup companies employing nearly 900 people.

Opened in 2010, the 19-acre Railroad Park includes a lake, restaurant, and other amenities and has become a major downtown destination. Photo by Kendrick Disch

Opened in 2010, the 19-acre Railroad Park includes a lake, restaurant, and other amenities and has become a major downtown destination. Photo by Kendrick DischUAB and its renowned medical complex, of course, are the economy's linchpin, employing 23,000 people and attracting the 10th highest research funding among public universities from the National Institutes of Health in 2015. Nearly twice as many jobs are in education and health services as manufacturing.

In fact, Birmingham's metro area employment is less concentrated in manufacturing than Alabama's or the nation's. Manufacturing is not dead, to be sure. Birmingham sits between automotive assembly plants in Talladega (Honda) and Tuscaloosa (Mercedes) counties. Neither plant is in the Birmingham metro area, but many of the plants' several thousand workers live in the Birmingham area. And parts suppliers in the Birmingham metro area employ some 3,000 people, according to BLS data. Metal makers also still employ more than 6,000 in Jefferson County.

For all its progress, Birmingham has never rivaled the spectacular economic growth of the Sun Belt's supernovas (see the chart). While it is impossible to apportion blame to Birmingham's history, the unsavory chapters of the city's past clearly have played a role.

An old motto laments that "hard times come to Birmingham first and stay longest." Many of Birmingham's founding families have also stayed. Lesley McClure, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta's Birmingham-based regional executive, says she frequently interacts with descendants of the city's founding business leaders. In fact, many of those descendants have contributed to bettering their hometown's economy and culture.

Today's Birmingham appears to have largely, yet perhaps not completely, escaped its historical shadow.