Photo courtesy of Amazon

Photo courtesy of Amazon

During six weeks of the holiday season, Geodis Contract Logistics of Brentwood, Tennessee, fulfilled about a million electronic commerce orders a day.

From its 130-plus warehouses, the firm aims to ship every ecommerce order as quickly as possible, said Scott McWilliams, Geodis's executive vice president of strategic development and a former member of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta's Nashville Branch board of directors.

Geodis manages distribution centers for customers including Samsung, DSW, H&M, and Duluth Trading. Across the economy, efficiently receiving, storing, delivering, and taking returns of millions of products a day, ranging from big-screen televisions to earrings, is a complex logistical puzzle. And with the rise of ecommerce, more and more products are delivered not to retail stores but to consumers' homes, introducing yet more variables into an intricate equation, McWilliams explained.

Ecommerce is indeed growing fast. Though still less than a tenth of overall retail sales, in the third quarter of 2017, retail ecommerce revenue climbed at four times the pace of total retail sales, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Executives of one big traditional retailer, Walmart, have said they expect ecommerce sales to continue to grow at around a rate of 50 percent year over year, the company reported in the August–October period.

As online sales expand, so do the size and number of distribution hubs that must stock vast selections of goods to be delivered directly to shoppers. At the same time, available industrial real estate—such as warehouse space—is relatively scarce following years of limited construction.

Building a huge, state-of-the-art warehouse is complicated. Operating one is probably even harder.

For starters, finding the right terrain is difficult—it has to be large enough, level enough, and near interstate highways or population centers. Then builders have to construct a laser-leveled floor so that forklifts or products on 36-foot-high racks aren't rattled or damaged. What's more, the floors must be thick enough to bear enormous weight—including fleets of five-ton forklifts—without cracking.

Managing once-humble warehouse now a science

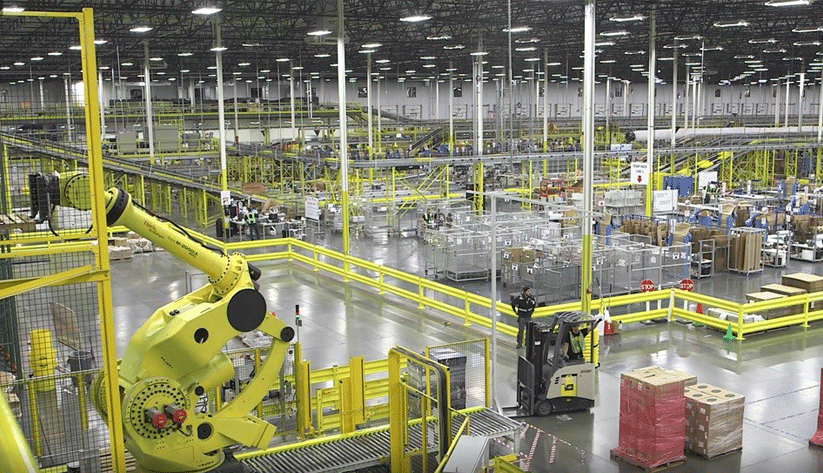

Advances in technology and knowledge have made warehouse management practically a branch of science unto itself. According to the book Warehouse & Distribution Science, by John Bartholdi and Steven Hackman, supply chain professors at Georgia Tech, the science boils down to meticulously managing the use of space and time. Time means worker pay. Space means cost—for heat, sprinkler systems, equipment, rent, power, and so on.

To save time, Bartholdi and Hackman recommend minimizing "total travel" of workers within a warehouse. So the traditional warehouse operating mode of "man to goods," or workers moving to products stored in more or less fixed locations, is shifting to a "goods to man" philosophy, explained Scott McWilliams, executive vice president of Geodis Contract Logistics and a former member of the board of directors of the Atlanta Fed's Nashville Branch. Technology such as robots, automated forklifts, and even mobile shelves allows workers to move more quickly between tasks.

Many times more data available

Partly because of an information explosion, there are now far more ways to refine the use of space and time. Supply chains today have 50 times more data available to them than just five years ago, according to the research firm International Data Corporation—information that contains plenty of unrealized potential, as less than 25 percent of the data are analyzed in near real time.

Using data to track exactly what's in stock, and its location, is critical. "Inventory accuracy is probably the most important facet of being able to handle these goods efficiently," McWilliams said.

One objective of tracking inventory is minimizing the number of boxes shipped. The idea is to maximize the number of items packed into each box while minimizing packing material and avoiding damaging items during shipment. The same principle applies to trucks—a warehouse manager aims to keep trailers packed.

Forecasting demand is key to inventory management. Retailers, especially in ecommerce, offer price promotions to smooth customer demand. A steady flow of merchandise is easier to manage than sales spikes and dips.

Beyond promotions, even more advanced methods of anticipating demand may be on the horizon. An April 2017 report from the consulting firm McKinsey & Company foresees "predictive shipping." Under this scenario, based on sophisticated algorithms, companies would ship a product before an order comes in, and then match the order when it came with a shipment already in progress. The shipment would then be rerouted to the customer's location.

These developments have combined to fuel a warehouse-building binge. Construction spending on general commercial warehouses reached a record $24.2 billion in 2017, according to Haver Analytics data gathered from the U.S. Census Bureau. On average, in inflation-adjusted 2017 dollars, warehouse construction spending increased 29 percent annually over the past five years, compared to 1 percent per year during the previous 19 years (see the chart).

Atlanta Fed interested in lending, prices

Why would the Atlanta Fed take an interest in warehouse construction? One important reason is that financial regulators take note of surges in commercial real estate (CRE). Increased activity could signal a similar surge in bank lending and thus raise concerns of too much financial risk concentrated in one industry sector. Second, technology that is fueling ecommerce warehouse development and wringing costs from supply chains could be suppressing inflation.

Start with the regulatory side. A hot streak in any CRE category inevitably creates conditions for potential overinvestment, which can lead to concerns for lenders, pointed out Brian Bailey, a CRE expert in the Atlanta Fed's Supervision and Regulation Division.

For now, banks do not appear overexposed to industrial real estate, Bailey said. Much financing for large warehouse construction is originating outside banks: from real estate investment trusts, private equity investors, foreign financiers, and building owners and operators such as retailers and logistics firms, Bailey said.

Industrial real estate appears to be on solid footing

To be sure, even for regulators, CRE data are not cut-and-dried. Under the CRE heading in the reports that financial institutions file with regulators, banks are required to separately categorize only lending used to finance multifamily residential projects. Other CRE lending is essentially classified as "other." Therefore, Bailey pointed out, it is difficult to gauge precisely bank lending to finance specific CRE categories such as industrial, office, and retail space.

It is reasonably clear, though, that the bigger the warehouse, the higher the cost, and the more difficult it becomes for smaller banks to make such loans, he said.

Heading into 2018, the fundamentals in industrial real estate appear healthy. Rents are steady, and vacancy rates remain at historically low levels: around 5 percent. In the Southeast, about 70 percent of the space in the largest warehouses—those 500,000 square feet and up—is leased immediately upon completion of the buildings, Bailey said. That "absorption rate," as it's known in the real estate industry, is an unusually robust one.

The quickening pace of warehouse construction allows the industry to remedy a shortage of space, experts said. In the past four years, spending on general warehouse construction was nearly triple that of the previous four years.

Industrial real estate is on a "once-in-a-generation" roll that should continue mainly because of soaring ecommerce, Dan Patillo, president of Atlanta industrial developer Rooker Real Estate, said during a December 2017 forum at the Atlanta Fed. And though the outlook is bright, Bailey noted that bank regulators will nevertheless remain vigilant. As 2017 ended, the appetite for industrial space was luring developers from other, less active real estate sectors, raising the specter of overbuilding by developers less experienced in the industrial market, Patillo said.

Bailey warned that the boom cycle could end. Late-arriving investors risk getting burned as the market weakens and borrowers face a tougher time filling their buildings and thus repaying debt, he explained.

"This trend of everything delivered to the home could pull back a little. Or the big ecommerce players could get so efficient they drive a lot of people out of business, and so the overall market needs less square footage," Bailey said. "A downturn in industrial real estate is not going to happen tomorrow, and probably not next year. But we have to think about it."

Efficient supply chains among many factors slowing inflation

What about the impact on inflation? Advances in technology that have reduced the costs of producing, storing, and delivering goods may indeed be helping to keep inflation below the Fed's objective of 2 percent, Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic said in a recent speech. But it is unclear exactly how much technology-induced reductions in production and distribution costs are responsible, in Bostic's view. (Technology has also allowed consumers to comparison shop online, which many economists believe also has dampened inflation.)

Advances in technology should, in fact, press costs lower, Bostic said. At the same time, though, smarter machines should spark productivity growth, and that growth has been unusually weak during the economic recovery, Bostic pointed out. No doubt, he acknowledged, it could be hard to measure productivity amid such rapid technological change throughout the economy.

"However, it is not yet clear to me that the measurement issue is large enough to resolve the inflation puzzle of the last five years or so," the Atlanta Fed president said in September.

Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic. Photo by David Fine

Warehouses getting bigger and bigger

Online shoppers' growing demands have made large, technologically advanced warehouses particularly popular. One Geodis customer stocks about 10 times the inventory of a typical retail superstore in a single warehouse. Customers like this have fueled the need to build ever-larger and taller warehouses. Standard ceiling heights have risen to 36 to 40 feet from 24 feet.

"The size of distribution centers has grown enormously," McWilliams said.

In metropolitan Atlanta, for example, the average industrial building completed in 2017 was more than four times bigger than the average one finished in 2000, according to data from the real estate research firm CoStar Group Inc.

Online merchants stock more product than traditional distribution centers because consumers expect to get what they want almost immediately. In the past several years, the ecommerce giant Amazon has opened about a dozen fulfillment centers in Florida, Georgia, and Tennessee, according to media reports and news releases from Amazon and economic development agencies.

Many Amazon warehouses sprawl over at least a million square feet, and some other firms' distribution centers are even bigger. Sports apparel maker Nike in 2015 opened one of the nation's largest warehouses in Memphis, Tennessee, with 2.8 million square feet (64 acres) and 33 miles of conveyor belts under one roof.

So although regulators will keep a watchful eye on this aspect of CRE, the growth and increased sophistication of warehouses are striking manifestations of the rapidly evolving habits of U.S. shoppers.