Stuart Andreason

March 28, 2018

2018-03

https://doi.org/10.29338/wc2018-03

Primary issue

Young workers are one of the most populous and diverse generations in some time and they have already become the dominant group in the workforce. A recent Pew study shows millennials make up 34 percent of the workforce.

Although there is optimism with new workers entering the workforce and millennials advancing in their careers, a significant group of young adults—often referred to as "opportunity youth"—are disconnected from the workforce or disadvantaged in the labor market. Opportunity youth often face major barriers to work, including limited transportation options, childcare challenges, health or mental health issues, detachment from the educational system, and criminal backgrounds, among other barriers.1 The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act places special emphasis on serving opportunity youth who have life experiences that have created barriers to work.

Integrating young workers into the workforce, especially opportunity youth, takes a deliberate approach. Considering the needs and perspectives of young workers is critical to integrating them into the workforce. Involving young adults and opportunity youth in the design and development of programs and curricula that prepare them for work will help ensure that the programs address challenges young workers face in the labor market. Creating opportunities for early work experience also plays an important role.

Existing research

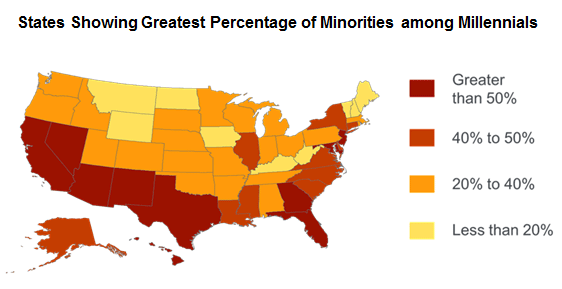

Young populations show greater levels of racial and ethnic diversity than ever before. Estimates suggest that by 2045, the United States will be a "majority minority" or a "minority white" country, the change driven by diversity among younger generations. In fact, among millennials, people of color already make up the majority of the population in California, Texas, Florida, Maryland, and Georgia, among a number of other states (see the map).

Source: 2015 U.S. Census population estimates, analysis by William H. Frey, "The Millennial Generation: A Demographic Bridge to America’s Diverse Future," Brookings Institution

This diversity brings new dynamism to the country—and increasingly complex demographics. Between 2018 and 2060, multiracial populations are projected to be the fastest-growing racial or ethnic group at 175 percent. Following closely behind will be Asians with 93 percent projected growth and Hispanics with 85 percent projected growth. The diversity is increasingly concentrated in urban and suburban areas for millennials; rural areas remain primarily white in this age group.

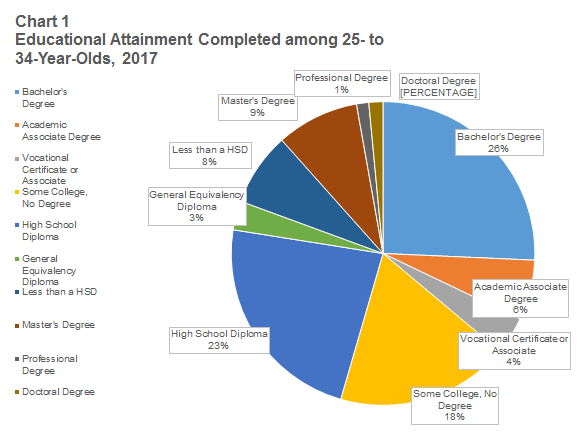

Not only are millennials driving racial and ethnic diversity, but also they are driving increasingly high levels of educational attainment. But while the generation has higher levels of educational attainment beyond college, the majority of millennials aged 25 to 34 do not have a college degree. Nearly two out of three people in the age group hold less than a bachelor's degree (see chart 1).

Source: Author's analysis of U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey, 2017 Annual Social and Economic Supplement

Finding educational opportunities that support young adults' career goals is critical. Despite recent policy attention on building additional opportunities for technical or vocationally focused educational credentials, a smaller proportion of 25- to 34-year-olds hold a vocational associate's degree or certificate than older age groups. A far lower proportion of the population among young adults hold a high school degree or less than workers over 55 years old, but it remains roughly one in three 25- to 34-year-olds.2 With advances in technology and increasing demand for skill in the labor market, this is a concerning trend.

The Center for Workforce and Economic Opportunity's Opportunity Occupations Monitor shows very few states where one in three jobs requires a high school diploma or less. Similarly, the tool shows even fewer of these positions pay over the regionally adjusted median wage. The National Skills Coalition finds similar trends in its analysis of middle-skills jobs: an oversupply of low-skill workers for the number of low-skill jobs available.

| Educational Attainment | 25- to 34-Years-Old | 35- to 54-Years-Old | 55 Years and Older |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 37.3 | 36.8 | 30.3 |

| Vocational associate’s or certificate | 4.0 | 4.7 | 4.3 |

| Academic associate’s or some college | 24.8 | 21.8 | 21.6 |

| High school diploma, GED, or less | 33.9 | 37.1 | 44.1 |

Note: Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding.

Source: Author's analysis of U.S. Census Bureau's Current Population Survey, 2017 Annual Social and Economic Supplement

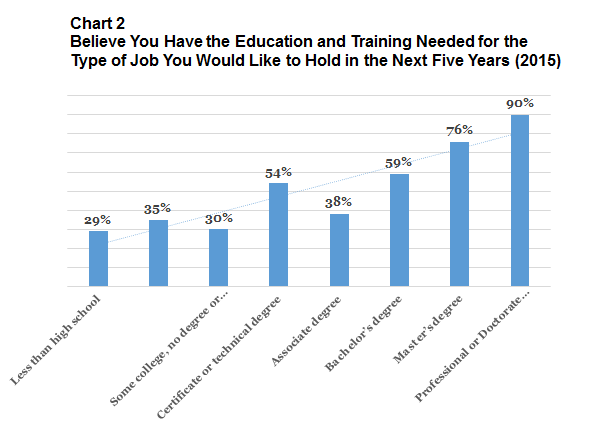

These educational differences play out in the perspectives that young workers have on the economy. The Federal Reserve Board of Governor's Survey of Young Workers shows respondents with higher levels of education were more likely to be optimistic about their future job prospects. Only 47 percent of young workers with a high school diploma or less reported optimism in 2015; meanwhile, 69 percent of young workers with a bachelor's degree reported optimism, and the number rose to 84 percent for those with a professional degree or doctorate. Among respondents who held a certificate or technical degree, 54 percent reported believing they had the education for the job they would hold in the next five years compared to only 38 percent of those with an associate's degree. Minority young adults also reported lower rates of receiving information on careers from parents or friends than their white counterparts.

Additional disparities in the labor market are evident between young adult populations. In July 2017, the youth unemployment rate was 9.6 percent—much higher than the national rate of 4.3 percent. It may be understandable the youth unemployment rate is higher since many young workers lack job experience or transition between jobs more rapidly. The unemployment rate for young white workers stood at 8.0 percent, while the rate for young black workers was 16.4 percent. There are few compelling explanations for the differences in unemployment rates between races. The February 2018 Workforce Currents, "Racial Disparities in the Labor Market," explored these issues in more detail. An increasingly diverse young generation suggests that finding ways to solve and eliminate these disparities could have a significant effect on economic opportunity in the future.

Policy implications

Engaging young workers is a central component to the future of the workforce, but increasing diversity means that programs need to meet these workers' unique needs. That likely means engaging youth much more actively in policy discussions, program development, and agenda setting in youth focused workforce development programs. Collaboration—or even co-creation of these policies and programs with youth—provides opportunities to incorporate the diverse experiences and perspectives of young adults.

Additionally, there are several broad policies that help young workers succeed as well as benefit society. Early exposure to work experience is also an important way to increase opportunity among young adults. Despite the importance of getting exposure to work, only 7 percent of young workers in the Fed survey reported receiving information on careers from a business they worked at while in high school. Thirteen percent reported getting information on jobs and careers at a business where they were employed in college.

Although few young workers report exposure to career information, youth summer employment programs show significant promise for young adults. Experimental evaluations of the Boston Summer Youth Employment Program showed statistically significant reductions in crime among participants, who also reported the program improved their job readiness, academic aspirations, and attitudes relative to control groups in the study. The largest gains were for minority youth. Other analysis suggests that career exposure through career and technical education programs improve traditional postsecondary academic performance and labor market outcomes for young adults. Expanding work experience opportunities to opportunity youth, in particular, could yield high returns to both the individuals and society.

Expanding youth employment opportunities and work experiences is necessary to reach more young workers. Currently, only 14 states have policies to support youth focused apprenticeships or pre-apprenticeships, and 11 states have other secondary student focused work-based learning programs. Since many states still have the opportunity to develop programs and policies on youth focused work-based learning, leadership in those states could incorporate youth in the development and formation of these programs.

Broadening opportunities for nondegree technical training is also an important part of preparing young workers for the labor market. Young workers have the lowest attainment rate of vocational focused associate's degrees or certificates, but the young workers who hold these credentials report similar optimism levels to those who hold bachelor's degrees. Given the need for more workers in middle-skill, technical focused positions, expanding access and incentives for young adults to pursue preparation and credentials for these positions could help increase opportunities for young workers (see chart 2).

Source: Heidi Kaplan, "Selected Findings from the Survey of Young Workers" presented at Creating a More Inclusive Economy summit in Atlanta, Georgia, on March 6, 2018

Finally, as young workers enter the workforce, many gain valuable work experience through alternative work arrangements rather than in full-time, steady employment. Young workers report less availability of benefits or training when working in such alternative jobs. Supporting young workers in these types of jobs by offering training and programs that help make incomes more stable and predictable could help them persist and earn experience, allowing them to move up.

Young workers, or millennials, are now the largest portion of the workforce. They are also the most diverse—and many of them face barriers to full integration into the workforce. Policies and programs, like early work experience, youth focused career and technical focused training and education, and work supports for nontraditional workers are just some of the ways to further integrate young adults into the workforce. Given the growing diversity of young workers, it is critical to consult and collaborate with them to incorporate their ideas and needs as communities look to support the development of a young workforce.

Many of these ideas were discussed at a recent convening, Creating a More Inclusive Economy: Igniting Systems That Produce Results for Youth Employment. The Atlanta Fed's Center for Workforce and Economic Opportunity, the Center for Law and Social Policy, MDC Inc., Opportunity Youth United, and Cities United cohosted the event. See the events page for additional resources.

Stuart Andreason is the director of the Center for Workforce and Economic Opportunity. The views expressed here are the author's and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta or the Federal Reserve System.

_______________________________________

1 For policies developed by the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) in the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act regarding young workers, see the WIOA Youth Program Fact Sheet. The term used by the DOL is "out-of-school youth," and many organizations have shifted to describing this population as "opportunity youth."

2 Young adults or workers are typically defined as workers from 18- to 34-years-old. The data above only report on educational attainment for those 25 to 34, so it is used here as the best approximation.