Raphael Bostic

Raphael Bostic

President and Chief Executive Officer

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

September 3, 2025

Key Points

- In his new quarterly message, Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic explains that amid extraordinary complexity in the economy, he focuses on fundamentals to frame his thinking.

- Bostic emphasizes that, while the federal funds rate the Fed controls directly influences short-term rates, it is not a dominant force that dictates all interest rates across the US economy.

- Bostic notes that the economy is in a transition period. Unlike most of the past several years, when risks to the inflation mandate were clearly the greater risk, risks to the employment mandate have increased such that the relative risks are more balanced.

- In formulating a monetary policy stance, Bostic explains that it is his duty to determine whether the risk of not reaching our inflation goal is greater than, smaller than, or the same as the risk of not hitting the maximum employment goal.

- He notes that the Fed has a dual mandate to pursue both price stability and maximum employment. If the Fed was like most central banks and pursued only price stability, then the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) would be unconcerned with employment and lowering the federal funds rate in this environment would be out of the question.

- Bostic also says the FOMC's revised strategic framework emphasizes the Committee's commitment to "act forcefully to ensure that longer-term inflation expectations remain well anchored, to the benefit of both sides of our dual mandate." This is a component of the strategy that he says is particularly salient.

Understanding a $30 trillion economy, a chore at any time, is especially complicated as we proceed further into 2025.

Uncertainty abounds. The full implications of trade policy remain unclear. It's not known how proposed federal deregulation and tax changes will manifest, nor the extent to which those shifts offset one another or tariff-related cost increases. Geopolitical uncertainties remain relevant.

Complexity confronts not just policy makers like me. At nearly every stop in my travels across the Southeast, I poll audiences on who feels confident in their business forecast for the next six months. In recent weeks, nary a hand has gone up.

For me, the job is calibrating monetary policy, which requires a clear read on the state of the US economy. Amid deep and wide complexity, I find that focusing on fundamentals helps to frame my thinking. So, before I detail my current economic and policy outlook, I will outline questions and tenets that underpin my policymaking process. These first principles, if you will, keep me locked in on the core mission.

First, how is the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) faring relative to the goals Congress has assigned us—achieving price stability and sustained maximum employment? How do I think the economy will evolve with respect to the two core objectives?

Committee participants must digest and analyze layer upon layer of data, anecdotal and survey feedback, research, the products of predictive models, and other material. Ultimately, though, the decision comes down to which is the greater risk: rising inflation or a deteriorating labor market. Of course, it's often not clear cut; the relative risks fall on a spectrum. Therefore, along with 18 other FOMC participants, I must determine where I think we are on that spectrum of risk.

Services prices still high, goods prices rising

To reach that judgment, I size up economic conditions.

Start with inflation. The Committee's preferred gauge, the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index, has run above our 2 percent target for four years. After substantial declines in the inflation rate starting in late 2022, progress essentially stalled in the fall of last year.

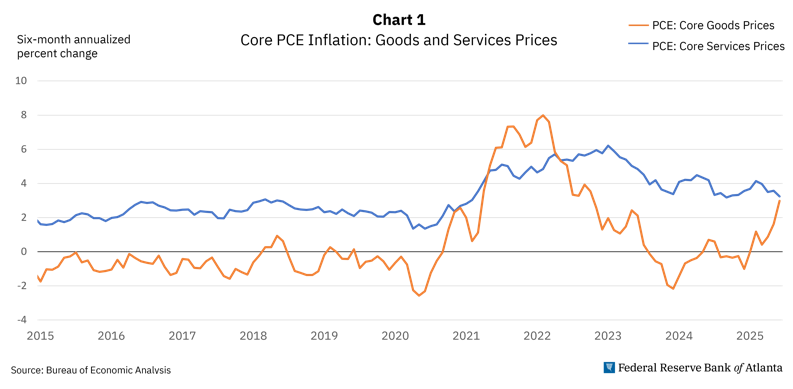

An important culprit: prices of core services—those other than energy services. As chart 1 shows, core services prices have lingered above prepandemic averages, preventing a fulsome return to the Committee's overall inflation target. To add to this, goods prices are also now increasing, a risk related in part to tariffs. For context, tariff rates across all US imports now average about 15 to 18 percent, compared to roughly 2 percent at the end of 2024.

The puzzle I'm grappling with is whether those inflationary effects of tariffs will quickly pass or prove more persistent. Even among FOMC participants, opinions on that question vary. I continue to believe that the effects of tariffs on consumer prices won't fade fast, and in fact will not fully materialize for some months. My view is based on input from business leaders and extensive research.

For example, a team of Atlanta Fed economists dug into results from our battery of surveys of business leaders and found that on net, their expectations of their own future prices have increased meaningfully since the end of 2024. It's not just firms directly affected by tariffs, either. Yes, the imposition of tariffs appears to be an important catalyst for the spike in price growth expectations. But the spillover onto firms that are not exposed to tariffs "raises the risk of a broad-based increase in inflation," the economists write.

I should add as a caveat that those results are probably sensitive to trade policy changes and therefore are best viewed as a risk to the inflation outlook should effective tariff rates remain largely unchanged from the first half of 2025. These findings are consistent with other research, including additional work from our team, the Yale Budget Lab, and economists connected to Harvard's Pricing Lab.

Our intelligence gathering team and I have heard similar messages from contacts in recent weeks. One, tariffs are indeed increasing costs. Two, most firms are absorbing those additional costs rather than boosting prices—so far. But three, most contacts may not have the capacity to eat higher costs much longer.

One nuance that has changed is that a majority of firms no longer expect to pass through to prices all the tariff cost increases. So, the ultimate impact on consumers might be more muted than it appeared a few months ago.

Lastly, on inflation, I'm concerned about the psyche of business leaders and households. If either or both begin to believe elevated price levels will stick for many months, then that belief can influence behavior in ways that lead to persistent inflation. As I noted, our surveys show business leaders have, in fact, raised their price expectations. Consumer inflation expectations, in contrast, have not risen too worryingly. But they do tend to be above the long-run target, clustered around 3 percent for one, three, and five years ahead, per the New York Fed.

Taken in total, these numbers give me pause. I will not be complacent and simply assume expectations will remain anchored and another inflation outbreak won't happen. My team and I will be monitoring developments regarding expectations quite closely.

One point that I don't think has been sufficiently emphasized is that, while the federal funds rate the Fed controls directly influences short-term rates, it's not a tectonic force that dictates all interest rates across the economy.

Just last year, for example, the Committee lowered the funds rate by a full percentage point—from a range of 5.25 to 5.5 percent to 4.25 to 4.5 percent over three meetings in September, November, and December. Over the same period, the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate actually increased. This is because yields on longer-duration assets, like 10-year Treasury securities and 30-year fixed-rate mortgages, are influenced by many factors other than monetary policy, such as investors' views of fiscal policy, national debt, and economic growth, among other factors.

My central point is that extraordinarily complex economic forces are at play. And it is important that policy makers, households, and businesses appreciate the depth and breadth of this complexity in making financial and economic decisions.

Labor market cooling, not collapsing

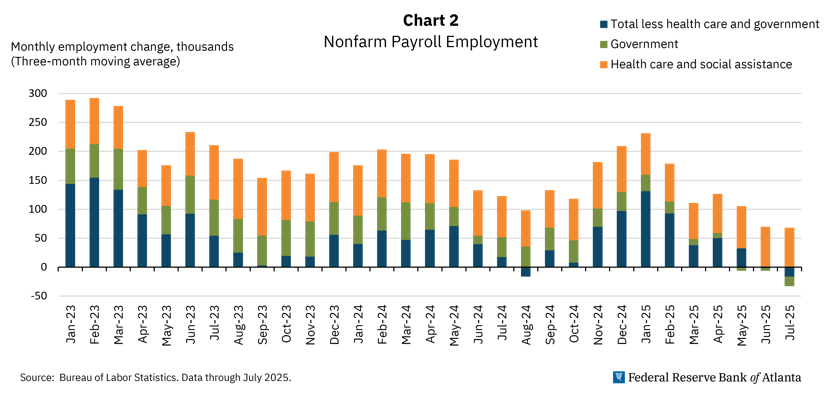

Turning to the other side of the dual mandate, the labor market has cooled sufficiently that the risks to the two mandated goals are likely coming closer to balanced. Monthly employment growth slowed significantly in the spring and summer, and it has for some time been overly concentrated in just a couple of sectors—notably health care (see chart 2). It is taking job seekers longer to find employment.

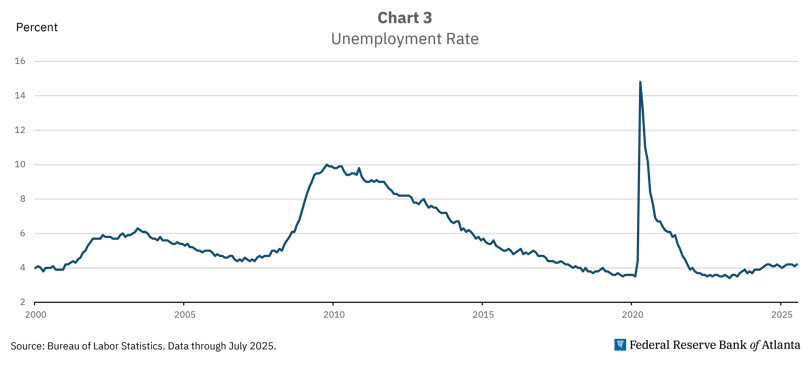

Nevertheless, for several reasons, I do not think it is unambiguously clear that the labor market is weakening materially relative to our mandated objectives. For one, we are not hearing alarming signals from business contacts. By and large, they are maintaining a "not-hiring-but-not firing" approach to payrolls. Second, labor supply has declined markedly, and so the unemployment rate has remained steady at just over 4 percent through the spring and summer (see chart 3). The US civilian labor force in July included 400,000 fewer people than it did in January, due to declines in net immigration and falling labor force participation. This sharp reduction in labor supply means that the number of jobs the economy needs to produce to break even—to keep the unemployment rate from rising—is much lower than we've seen in recent years. For context, estimates from our staff suggest that the breakeven level has declined from 125,000 to 150,000 new jobs a month to around 75,000 to 100,000 a month for 2025, and could continue to fall to a number below 50,000 per month in the next two years as the labor force is expected to grow at a slower pace.

For me, the takeaway on the labor market is this: If labor demand and labor supply are both slowing such that the unemployment rate is stable, then the labor market has not meaningfully weakened and, in fact, remains near full employment. In other words, we are still close to the Committee's maximum employment objective.

That said, I am not completely sanguine about employment. Signs of cooling bear scrutiny, as history tells us that the labor market can turn quickly and decisively. Former Fed economist Claudia Sahm developed a formula that has proven reliable—when the three-month moving average of the unemployment rate rises by 0.5 percentage points over the rate's 12-month low, then it keeps rising. Through July, the three-month moving average was just 0.2 percentage points above the 12-month low. So, again, that is not a shrieking alarm bell. But this bears watching.

Basic rules of formulating policy

In formulating a policy stance, it is my duty to determine whether the risk of not reaching our inflation goal is greater than, smaller than, or the same as the risk of not hitting the maximum employment goal. That formulation has become trickier in recent months, as the labor market slows even as inflation remains above target. Our economy is in a transition period. Unlike the majority of the past several years, when the risks to the inflation mandate were clearly greater than the risks to the employment mandate, risks to the employment mandate have increased such that the relative risks are more balanced.

Ultimately, my policy calculation comes down to the following: If the risk of not achieving price stability outweighs the risk of not achieving maximum employment, then the Committee probably wants restrictive policy that will curb inflation. On the other hand, if the greater risk is to the health of the labor market, then we may want policy to ease, or be mildly stimulative to support employment. If I conclude that the risks to both sides of the dual mandate are in fact equal, then we might want the federal funds rate to be at or near neutral, or a stance that is neither restrictive nor stimulative.

Today, I judge policy to be marginally restrictive. I believe that, while price stability remains the primary concern, the labor market is slowing enough that some easing in policy—probably on the order of 25 basis points—will be appropriate over the remainder of this year. That could change, depending on the trajectory of inflation and the evolution of employment markets in the coming months. I am and remain, after all, data dependent.

The value of the dual mandate

In this essay, I have attempted to be completely transparent in summarizing the policymaking approach of this FOMC participant. It is a delicate blend of science and art. That is especially the case because the Fed's dual mandate is unusual among major central banks around the world. If the Fed was like most central banks and pursued only price stability, then the Committee would be unconcerned with the employment implications of monetary policy. Lowering the federal funds rate in this environment would be out of the question.

The dual mandate, however, demands that we weigh difficult trade-offs. As I detailed in a recent speech, I believe the dual mandate serves the American public well. If you spend time following the Fed, you have undoubtedly heard Fed Chair Jerome Powell declare that price stability is necessary to achieve long-term labor market expansions that benefit all of our citizens. I agree, and I think that formulation succinctly captures the mutually reinforcing nature of the dual mandate.

I also believe that pursuing the two core objectives makes me a more well-rounded central banker. Cultivating conditions favorable to price stability and maximum employment requires a deep and nuanced appreciation for how economic activity actually happens—how products are produced and services delivered, how firms set prices, how and why hiring and investment occurs or does not, the mechanics of supply chains, financing, trends, strategies, and so on.

The FOMC has a statutory obligation to pursue two goals, and it's not always easy. But that's the mandate. And a mandate serves to focus one's energy even in times of great uncertainty, like the present.

A few reflections on our updated framework

In closing, I'll offer a couple of thoughts on the strategic framework review of our long-run policy strategy that the Committee just wrapped up. As Chair Powell described in an August speech, the revised framework emphasizes our commitment to "act forcefully to ensure that longer-term inflation expectations remain well anchored, to the benefit of both sides of our dual mandate." This is a component of the strategy that I feel is particularly salient, as I detailed in my aforementioned July speech.

The updated strategic framework also makes explicit the approach I described above that is guiding us today as we contemplate the stance and trajectory of policy. We consider the extent that each mandate dimension has departed from its stated goal as well as the potentially different time horizons it will take to achieve each goal.

I encourage you to read Chair Powell's August Jackson Hole speech for more on the revised strategic framework. Thank you for reading this message, and rest assured that the Committee will continue doing all we can to bring about both price stability and sustained maximum employment for the benefit of all Americans.