The share of the prime-age population engaged in the U.S. labor market is on the rise, led by a sharp rebound in the labor force participation (LFP) rate by prime-age female workers (those ages 25–54). This point was highlighted in a recent Wall Street Journal article.

Since 2015 the LFP rate for prime-age women has increased by about 1.8 percentage points, reversing an almost 16-year slide. Using the data underlying the Atlanta Fed’s new Labor Force Participation Dynamics tool, some of the factors behind this increase become apparent. Of particular note is that Hispanics (people of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin regardless of race) account for a bit less than one-fifth of the prime-age female population, but they accounted for almost two-thirds of the increase in female LFP during the last three years. This increase was the result of both a rising share of the population that is Hispanic and the rising LFP rate among Hispanic women. The share of the prime-age, Latina population increased by 1 percentage point between 2015 and 2018, and the LFP rate for this group increased 3 percentage points. (The reason why rising Hispanic LFP didn’t result in the overall female LFP rate increasing by more than 1.8 percentage points is because Hispanic women are still 8 percentage points less likely to be in the labor force than non-Hispanic women. But this participation gap is closing rapidly.)

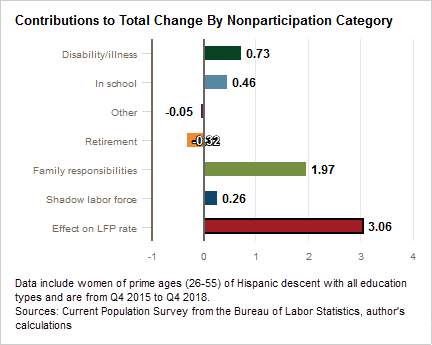

The Atlanta Fed’s web tool also allows us to further explore what is behind the 3 percentage point LFP rate increase for prime-age Latinas in the last three years. (My Atlanta Fed colleague Ellyn Terry provides a longer-term view on Hispanic female labor force dynamics in this related macroblog post.) It’s particularly noteworthy that almost two-thirds of the recent increase is the result of a decline in family or household responsibilities keeping people out of the labor force (see the chart).

This shift away from household duties is attributable to a combination of the shifting demographics of the Hispanic population (such as being more likely to have a college degree and thus obtaining a higher-wage job and being better able to afford child care) and a lower propensity to not participate for family reasons within Hispanic age and education groups.

The rebound in female LFP in the last three years is good news, with rising wages, particularly at the low end, and higher demand in traditionally female-dominated occupations contributing to the increase. But making the labor market a truly viable option for women still poses a number of challenges. The LFP rate of U.S. women has fallen behind that of many other countries, many of which have enacted family-friendly policies to help support women in the workplace.

By

By