Without question, the U.S. labor market has tightened a lot over the last few years. But a shifting trend in labor force participation—and especially a rise in the propensity to seek employment by those in their prime working years—seems to be relieving some labor market pressure.

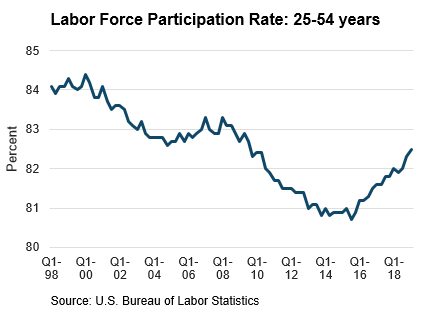

From the first quarter of 2015 to the first quarter of 2019, the labor force participation (LFP) rate among prime-age workers (those between 25 and 54 years old) increased by about 1.5 percentage points (see the chart below), adding about 2 million workers more than if the participation rate had not increased.

Changes in the distribution of the prime-age population in terms of age, education, and race/ethnicity toward groups with higher participation rates and away from groups with lower rates accounts for about a third of the rise in the overall prime-age LFP rate. The other two thirds can be pinned on an increase in LFP rates within demographic groups—what we call "behavioral" effects.

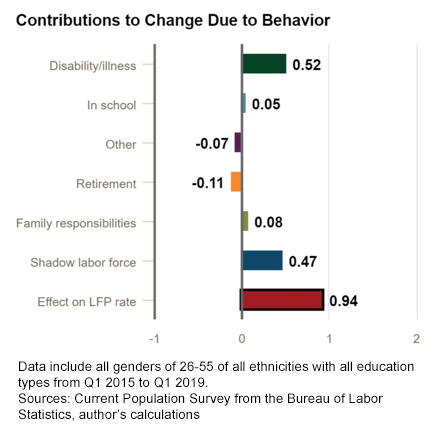

Of the increased participation behavior within demographic groups, there has been a decline in the share of the prime-age population that say they want a job but are not actively looking for work at the moment. We refer to these individuals as the "shadow labor force" because even though they are not in the labor force this month, they have a relatively high propensity to have a job next month. Second, there's been a decline in the share of the prime-age population that are not participating because they are too sick or disabled to work. The contribution of the change in behavior in these two categories (as well as several others from the first quarter of 2015 to the first quarter of 2019) are shown in the following chart, which is taken from the Atlanta Fed's Labor Force Participation Dynamics tool.

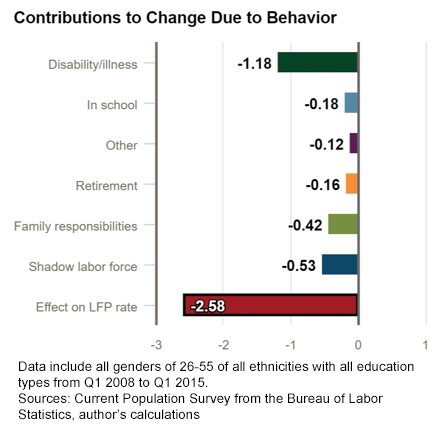

In contrast, consider the period from the first quarter of 2008 through the first quarter of 2015, a time when the rate of prime-age LFP declined by almost 2 percentage points. During that period, even though slow-moving demographic changes were putting modest upward pressure on the prime-age participation rate, that support was more than swamped by negative changes in participation rates within demographic groups. The following chart shows the relative contributions of these behavioral changes.

Within demographic groups, the increased incidence of being too sick or disabled to work stands out as the largest contributor to the decline in prime-age labor force participation between 2008 and 2014.

Since 2014, prime-age LFP has benefited from the movement of both demographics and participation behavior. But so far, less than half of the overall behavioral decline between 2008 and 2014 has been reversed.

Though demographic trends are likely to remain positive, how much more participation behavior—especially as it is related to disability and illness—can shift as the labor market tightens remains unclear. The share of the prime-age population too sick or disabled to work had been on a rising trend for the decade prior to the last recession, suggesting that there may be some deeper and structural health-related issues that could keep the disability/illness rate elevated despite an increasingly tight labor market.

By

By