Reports about the economic fallout from the coronavirus pandemic and efforts to slow its spread make for grim reading. One especially grim statistic is the number of layoffs. Since early March, just over 28 million persons have filed new claims for unemployment insurance benefits (roughly 30 million if you seasonally adjust).

Some analysts anticipate that as a result, the unemployment rate for April will be above 20 percent. By way of comparison, the unemployment rate peaked at 10 percent in October 2009 in the midst of the Great Recession and 24.9 percent (by one measure) during the Great Depression.

The extraordinary scale of recent job losses commands attention, and rightly so. But there's more to the story of recent labor market developments: quite a few firms are also hiring new workers in response to pandemic-induced demand increases. In fact, the latest Survey of Business Uncertainty (SBU) says that, for the U.S. economy overall, the COVID-19 shock caused three new hires for every 10 layoffs.

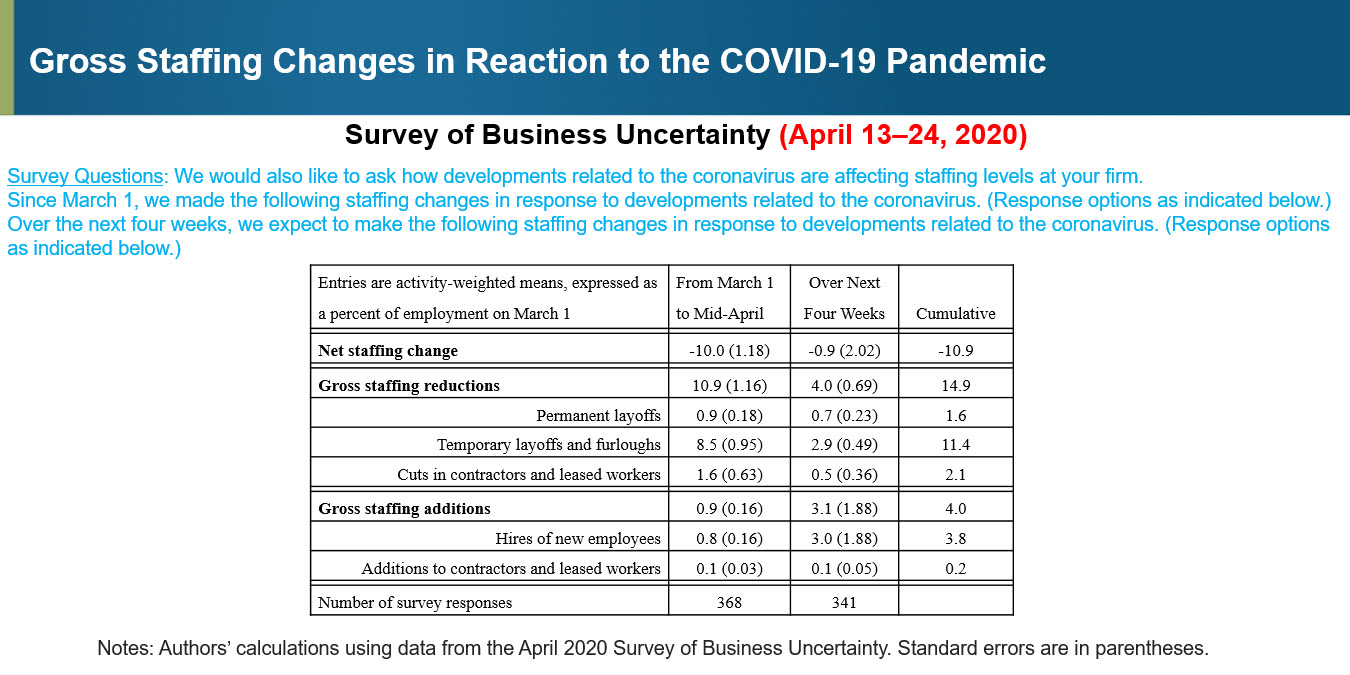

In the latest wave of the SBU (fielded from April 13–24), we posed two special questions about staffing changes. The first question asks how developments related to the coronavirus caused firms to alter their staffing levels since March 1 across five categories: permanent layoffs, temporary layoffs and furloughs, new hires, cuts to the number of contractors and leased workers, and additions to the number of contractors and leased workers. A follow-up question asks panelists what staffing changes they plan to make over the ensuing four weeks in response to coronavirus-related developments.

The chart below examines all of the changes firms can make in staffing levels (layoffs, hiring, changes in contractors, etc.) and isolates the percentage changes associated with each type of action. These changes include total (or gross) reductions, gross additions, and the net impact on staffing levels (that is, gross additions minus gross reductions). The results presented in the chart are striking. Between March 1 and mid-April, firms implemented gross staffing reductions equal to 10.9 percent of employment. During the ensuing four weeks, they plan additional cuts equal to 4 percent of employment. The sum of these two figures yields gross staffing reductions over two and a half months equal to 14.9 percent of March 1 employment—a staggering job loss rate, to be sure.

But there's another aspect to the story. In the same span of two and a half months, coronavirus-related developments caused firms to increase gross staffing levels by an amount that equals 4 percent of March 1 employment. In other words, the COVID-19 shock led to roughly three new hires for every 10 layoffs. The exact ratio is a bit less than 3 to 10, especially if we include contractors and leased workers. This result aligns with news reports of large-scale hiring at firms like Amazon, Walmart, CVS Healthcare, Domino's Pizza, and other companies that saw increased demand in reaction to the pandemic and partial shutdown.

There are good reasons to think that our survey results actually understate the true extent of gross staffing gains and losses in reaction to the pandemic. First, the SBU undersamples younger firms. (We know from other research that young firms have higher gross staffing gain and loss rates on average.) Second, highly stressed firms are less likely to respond to surveys, which means that our results probably understate gross staffing reductions. Third, our survey does not capture hiring by new firms. U.S. Census Bureau statistics (derived from administrative sources) say that business formations continue even in the wake of the pandemic. Since the latter part of March, applications for new businesses that the Census Bureau regards as having a "high propensity" to hire workers in the near future are running at about two-thirds of the 2019 pace.

The chart also sheds light on the nature of staffing reductions from the employer perspective: More than three quarters of these reductions are temporary layoffs and furloughs, implying that most workers will return to their old jobs, which can happen more quickly than hiring new employees (or those individuals finding a new job). However, this expectation warrants some skepticism. As we reported last month, SBU panel members express record-high levels of uncertainty in the outlooks for their firms, a reading that sounds right to us. No one yet knows how rapidly the pandemic will recede, or how much permanent economic damage it will cause.

By

By  Jose Maria Barrero, assistant professor of finance at Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México Business School,

Jose Maria Barrero, assistant professor of finance at Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México Business School, Nick Bloom, the William D. Eberle Professor of Economics at Stanford University,

Nick Bloom, the William D. Eberle Professor of Economics at Stanford University, Steven J. Davis, the William H. Abbott Professor of International Business and Economics at the Chicago Booth School of Business and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution,

Steven J. Davis, the William H. Abbott Professor of International Business and Economics at the Chicago Booth School of Business and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution,

Nick Parker, the Atlanta Fed's director of surveys

Nick Parker, the Atlanta Fed's director of surveys