The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has had a shockingly large and swift impact on the U.S. economy since mid-March. And the initial coordinated federal response to the virus was, perhaps, equally swift, as Congress passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act by the end of March. Further evidence of the speed of this reaction is that one of its main programs—the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP)—began taking applications by the first week of April, and it took only 13 days to deplete the initial funding amount.

Some analysts have suggested that emergency financial assistance to firms may have had a hand in May's surprisingly strong employment report, although not all the feedback on the PPP has been uniformly positive.

To shed further light on firms' experiences seeking and obtaining financial assistance during the pandemic, we posed a battery of special questions to our Business Inflation Expectations (BIE) panel in June (the survey was fielded from June 8 to June 12).

We first posed two questions regarding whether firms have requested and received financial assistance since March 2020, and we actually borrowed these questions from the U.S. Census Bureau's Small Business Pulse Survey. We followed those questions up with two more questions asking what share of the financial assistance requested they eventually received and, of that, what share of the amount received did they expect to be forgiven.

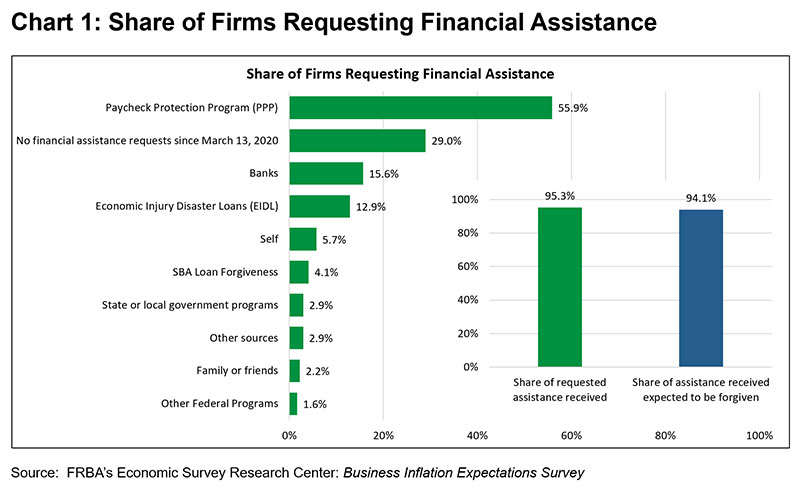

As chart 1 shows, about 70 percent of firms in our BIE panel requested financial assistance of any form (ranging from borrowing through an emergency facility, from a bank, and even from family and friends) since March 13, 2020. A majority of the panel sought financial assistance from the PPP. Digging into these responses, we find that very few firms sought multiple sources of assistance. Of the firms seeking financial assistance, three quarters of them sought assistance from only one source, and another fifth or so made requests from two sources.

Many applicant firms appear to have been successful in obtaining funding. The inset in chart 1 shows that, on average, firms received nearly all (95 percent) of the funding they sought. Perhaps more interesting is that, for the most part, firms expect most of these loans to be forgiven.

We should note that it's important to keep in mind that our sample includes only firms with employees, and our panel modestly overweights larger firms (the average firm size category in our sample is 50–99 employees). Given the varied experience that some businesses (and especially nonemployer firms, or very small businesses without employees, of which there are more than 25 million), our results cannot necessarily be generalized to the larger universe that includes nonemployer businesses.

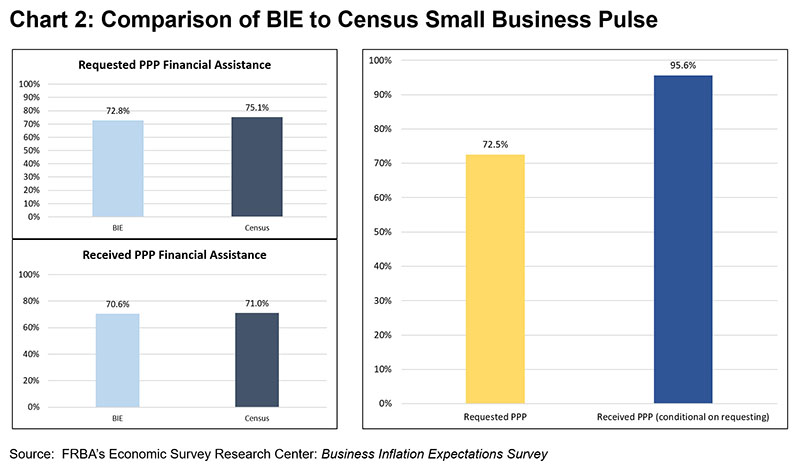

Given that an overwhelming majority of requests for and acquisitions of emergency funding came from the PPP, we focus our attention in chart 2 on small firms (those with 500 employees or fewer) and compare our results to the nationally representative sample of small firms from the Census Bureau's Pulse Survey. (The June survey from the National Federation of Independent Business found similar results.) Both the BIE and Census Bureau surveys found that roughly three quarters of small firms have requested financial assistance from the PPP since March 13 and that a little over 70 percent of small firms have received funding from the PPP (implying that a very low share of applications were denied). Although the Census survey stops there, our special questions ask about the amount of funding these firms received relative to their request. Small firms in the BIE panel received an average of 96 percent of the requested funding.

Nearly every survey respondent who received a PPP loan indicated that they expect it to be forgiven, which is interesting for two reasons. One of the stipulations for PPP loan forgiveness is the recipient firm's retaining or rehiring employees. Our results offer an early suggestion that most firms expect to be able to keep their headcount up. Second, it suggests that, as these firms begin to open up and recover from the pandemic, they won't bear the burden of loan repayment.

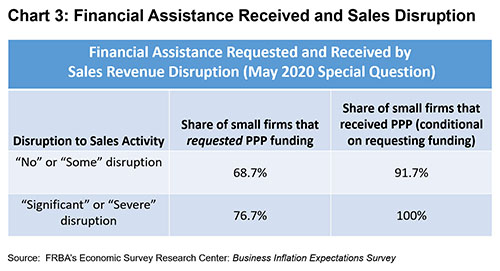

Analysts and the press often ask if PPP money is going to where it might be most effective (that is, to the firms that need the lifeline merely to survive). Although it's still too early to render anything resembling a verdict, we do have some tentative results that speak to this issue.

Last month, we asked firms in our panel about the level of pandemic-related sales disruption they have experienced, ranging from "no negative disruption" to "severe negative disruption." Of small firms that experienced little to no sales disruption in May, 69 percent applied for PPP funding. More than 90 percent of those applicants received assistance from the PPP (see chart 3). For the group that experienced more severe disruption to sales activity, 77 percent of these small firms applied for funding (and all applicants received funding). That still leaves nearly a quarter of small firms with significant disruption to sales activity that did not request PPP funding. (Our results do not indicate why a small firm under duress wouldn't seek assistance from the PPP.)

Overall, our results suggest (alongside data from the Census Bureau and others) that the majority of employer firms have requested some form of financial assistance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Firms report that most of those requests are being fulfilled and that they've received amounts close to what they requested. And—although these results are tentative as we are comparing results to firms' previous responses during a period of dramatic changes—it appears financial assistance is going to a greater share of firms that have experienced more significant disruption to their sales activity.

Nick Parker, the Atlanta Fed's director of surveys, and

Nick Parker, the Atlanta Fed's director of surveys, and Brian Prescott, economic research analyst, all in the Atlanta Fed's Research Department

Brian Prescott, economic research analyst, all in the Atlanta Fed's Research Department