Recent inflation reports have been disappointing, with core year-over-year inflation remaining well above the Federal Open Market Committee's long-run target. A major driver of the increase in recent months has been the rising price of shelter

(effectively the rental cost of housing), which has continued to accelerate. At the same time, data

highlighted by Jose Barrero, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven Davis, show that 31 percent of workdays are now spent remote, suggesting that much of the work-from-home patterns that developed during COVID may persist. In this context, it is interesting to ask whether underutilized office space could be repurposed as housing, thereby increasing the supply of housing units and slowing rent inflation. Certainly, many anecdotes in the press (such as here

and here

) discuss this possibility.

After a stunning surge in housing prices and rents, US cities are straining to produce enough units to meet the demand for new housing space. Meanwhile, economists have determined that the residential market needs significantly more density (read: verticality)—especially in the largest cities, where the tallest office buildings are located. However, building new multifamily housing is difficult. Zoning, building codes, height limits, parking requirements, and other regulations restrict the unit count of new multifamily housing and increase the cost of new construction, if they allow it at all. Incumbent residents often oppose new construction and block projects of sufficient scale. The barriers to new multifamily construction include factors such as:

- Economic constraints: Redevelopment is often more expensive than the status quo because it requires demolition or land assembly or both to combine parcels, which several experts have shown to add significant costs (see here

and here

).

-

Legal and social constraints: Building height limits

, neighborhood opposition, zoning, and other regulations and veto points can all stand in the way of changing the use and density of a property in a large metropolitan area.

- Structural constraints: New construction technology, compliance with new building codes, and new financing may all raise the cost of replacement above the marginal benefit of the new use of space.

Could existing office buildings, already built and now underutilized, be converted to housing?

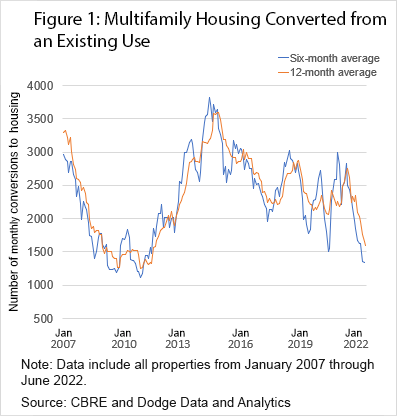

If owners of office buildings are undertaking conversions, their plans for change should show up in the SupplyTrack database, a joint product of CBRE and Dodge Data and Analytics that tracks as many commercial development projects as possible across the United States (see figure 1). Unlike the US Census Bureau's building permits database, SupplyTrack doesn't just tally new development. It also reveals redevelopment, like office-to-housing conversions.

SupplyTrack attempts to identify projects well before the permitting stage. On average, we can observe a multifamily project 16 months before it breaks ground and potentially well before the publicly available permit data. (I should note that some projects discovered by SupplyTrack never break ground. In this blog post, I impose an ad hoc cutoff of eight years and drop projects that were not started within eight years. Different cutoff dates do not materially affect the figures below.) An announced or discovered development project is one of the earliest indicators of the future of the construction cycle. Conversions to multifamily are typically identified even earlier—on average, 18 months before they start. One explanation for this is that conversion projects, unlike a vacant lot, are still producing a stream of revenue, so threshold return required to move forward might actually be higher.

Don't see a spike in planned conversions of office buildings after the COVID-19 pandemic hit? Neither do we.

From 2007 to 2019, SupplyTrack found that an average of 2,300 multifamily units were created monthly out of formerly office, warehouse, or industrial use. Historically, adaptation of existing structures is about 10 percent of newly supplied multifamily housing (in buildings with five or more units) or 3 percent of all housing units. Thus, conversions would need to ramp up massively to have an appreciable effect on rents. However, average conversions declined to just 2,053 a month from April 2000 through June 2020 and don't appear to be trending up. Importantly, these numbers aren't affected by any lengthening of construction time due to supply chain shortages because they represent starts rather than completions, and conversions to multifamily housing don't appear to be trending up.

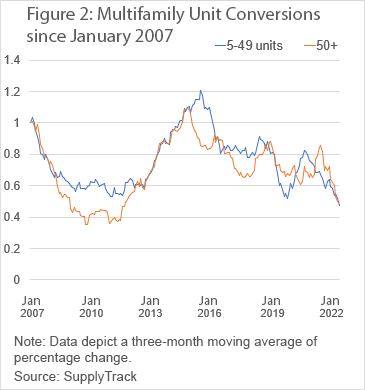

Of course, not all buildings are equally threatened by the work-from-home revolution. Perhaps larger office buildings in abandoned central business districts are better suited to conversion than the often-smaller office complexes distributed around the suburbs. To compare these categories on an equal footing, we indexed the annual conversion activity to 100 in 2007, indicating the relative percent change each year (see figure 2). Again, we see little evidence of a pandemic surge in conversions.

Large office buildings, which can be converted into 50 or more units, might seem especially attractive candidates for conversion—consider office towers in empty central business districts—but this category isn't unusually active. If anything, both large and small conversion projects appear to be declining.

Perhaps developers are confronting a daunting, even existential, question: is the office building really dead? Despite all the benefits of the work-from-home (WFH) model, economists have documented many ways that workers are more productive in person (see here, here

, and here

). Certainly, pausing can be an optimal response when uncertainty is high. One problem is likely, that most of the WFH hours are coming from hybrid work, not pure WFH. Hybrid work may raise productivity or increase the surplus to employees, but it may not actually free up much conventional office space. Whether firms will continue to lease space that is only used three days a week remains to be seen, but at the moment, the hybrid model appears to be keeping widespread conversion of offices to rental on hold. In any case, it seems unlikely that office conversions will blunt rental increases anytime soon.