The Federal Highway Act of 1956 connected Americas cities like never before, but the system of roads also divided and isolated existing city neighborhoods. As a result, people lost neighbors and local businesses and found themselves cut off from other parts of the city. Moreover, exposure to air and noise pollution increased, and some residents simply left the city altogether.

The recently passed Inflation Reduction Act included $3 billion in neighborhood access and equity grants, expanding on $1 billion in funding for the Reconnecting Communities Pilot

grants (part of the 2021 infrastructure bill

). These funds are intended to remediate some of the ill effects of urban freeways, and the grants could fund freeway removal or other mitigation strategies. The most ambitious projects, however, are likely to put "lids" composed of parks and surface streets over sections of existing freeways. Atlanta currently has three proposed lidding projects that are likely to compete for this funding: a park over Highway 400

in Buckhead, a park over the connector

(I-75/I-85) in Midtown between North Avenue and 10th Street, and a separate proposal

over the connector between downtown and Midtown around Peachtree Street.

Capping a freeway with a park and surface streets could play a significant part in ameliorating the unpleasantness of an urban freeway. However, these lidding projects are expensive to construct and maintain and don't completely eliminate air and noise pollution from freeways. Whether such projects are fiscally sustainable largely depends on their ability to attract new investment and residents to the city.

One of the more celebrated recent lidding projects is Klyde Warren Park, a five-acre park spanning three city blocks of freeway in downtown Dallas. The park was partly funded with an assessment on proximate land and, at least anecdotally, attracted considerable investment

to that area of Dallas. Like Atlanta, Dallas is a growing, low-density, largely auto-dependent Sunbelt city. If a freeway lid could attract new investment and residents to the city core, then such projects might have broader impact.

One challenge to evaluating any place-based project or subsidy is identifying the appropriate treatment area. Although a new park might attract investment or raise property values for immediately adjacent land, do such parks benefit the city as a whole? Or do they just redirect normal, market-driven development to a different location?

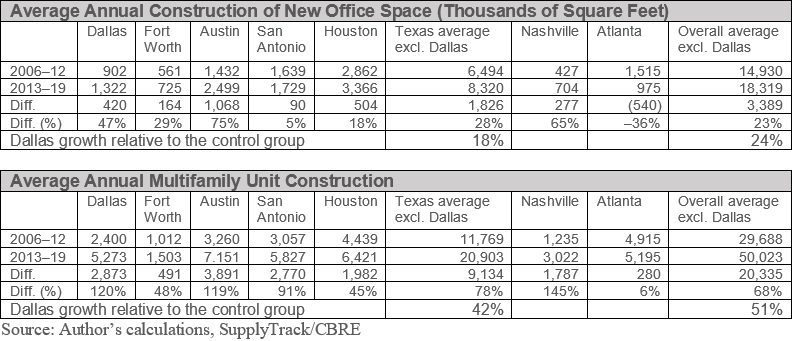

To look at whether the construction around Klyde Warren Park represented development beyond what might otherwise have happened, I looked at SupplyTrack data on new construction for six years before and after construction on the park began, both in Dallas and in a control group of six cities. I selected large southern cities not directly on the coast: Fort Worth, San Antonio, Austin, Houston, Nashville, and Atlanta. Looking before and after completion of the Dallas freeway lid and across cities, we can ask if the pace of new construction in Dallas increased relative to the control group. This is, effectively, a simple difference-in-difference estimate of the treatment effect of the freeway lid on Dallas. The table below summarizes the evidence on new construction.

Relative to its peers, Dallas experienced faster office and multifamily construction growth after lid construction began in 2012. Dallas added 1.3 million square feet of office space, a rate that is 50 percent faster than what occurred in the six prior years. Multifamily housing (apartments and condominiums in buildings with 5 or more units) grew even faster. Dallas added nearly 5,300 individual multifamily units after starting the lid, more than twice as many units as the six years before. I should note, though, that this period spans the housing market collapse of 2008. However, most large southern cities were doing well after 2012 as their economies slowly recovered from the Great Recession and developers took advantage of low interest rates. Still, compared to the control group cities, Dallas appeared to outperform. If we subtract the percentage growth in office and multifamily space from that of other large southern cities—either just in Texas or pooling all seven cities together—the growth in Dallas still looks exceptional. Compared to other Texas cities, Dallas office space grew 18 percent faster and multifamily grew 42 percent faster. In percentage growth terms Dallas's performance looks even better when we include Atlanta and Nashville in the control group, suggesting that whatever immediate growth that happened around the park did not simply divert growth from elsewhere in the city.

I also looked at the annual growth relative to 2012 for each city's hotels and retail space. Hotel room growth was weaker in Dallas than in peer cities, suggesting that new hotels built near the park might have come at the expense of other locations in the city and did not represent a net addition to supply. Perhaps parks are simply a more attractive amenity to residents than tourists, or maybe—given the relatively brief exposure—tourists were more indifferent to freeway noise and pollution ex ante. Retail growth never recovered after the Great Recession, but it didn't look particularly worse in Dallas than for the control group of cities.

Of course, none of this evidence is definitive. Cities are complex, and numerous idiosyncratic factors affect a cities labor demand, attractiveness to workers or their capacity to supply new houses and offices. Still, when looking at investment activity, Dallas's growth in multifamily and housing and office construction is at least consistent with the idea that building the Klyde Warren Park lid over the freeway in downtown Dallas made the city a more attractive place to live and work.