With some fine tuning, a 43-year-old banking statute could play a key part in addressing economic disparities that have plagued America for centuries.

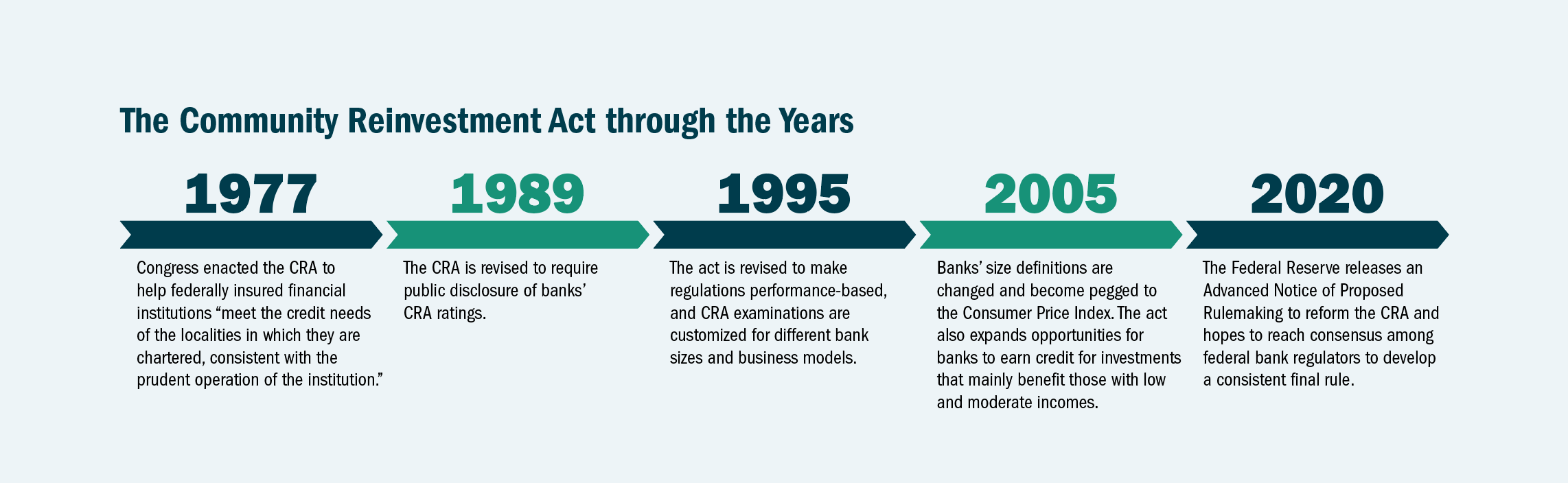

Ensuring equal access to credit is important in confronting inequities that the pandemic recession is worsening, including gaps in home ownership, household wealth, and employment and incomes. One of the major statutory means of making bank loans accessible, the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) was passed by Congress in 1977 to ensure that financial institutions served all the communities where they operate, particularly low- and moderate-income (LMI) and minority neighborhoods that have faced a history of disinvestment as well as discrimination in lending.

In September, the Federal Reserve Board of Governors approved an “Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking” aimed at establishing a framework for updating the CRA for the first time in years (see the timeline). The Fed proposal is built on ideas advanced by diverse stakeholders including mainstream banks, community development financial institutions, nonprofits, and the other federal banking regulatory agencies.

“The CRA remains as important today as ever, but to ensure its continued effectiveness, CRA regulations must evolve,” said Raphael Bostic, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. “In the 25 years since CRA was last reformed, the banking landscape has changed significantly, so it is important that we do it now, do it right, and ensure that we have broad support.”

The Board of Governors, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) have broad authority and responsibility for implementing the CRA. The three agencies examine institutions they regulate for compliance with the act.

The agencies are pursuing CRA reform because, as Bostic noted, banking conditions have shifted in significant ways. Notably, neither the 1970s-era CRA nor the mid-1990s update anticipated the rise of online banking and the related decline of physical branches. Also, community development has grown more complex. For example, when the act was last updated in 1995, disinvestment from urban areas was still a major concern. Today, by contrast, regulators are exploring the mixed effects of gentrification and trying to determine whether the CRA might be encouraging displacement of longtime residents of redeveloping LMI neighborhoods.

Additionally, the Fed aims to give financial institutions greater clarity and certainty on regulators’ CRA performance expectations. In its proposal, the Fed intends to tailor the regulations based on bank size and business strategy and minimize additional burdens on the banks.

“I think it’s important that we establish a baseline: that we believe policy and institutions should support opportunity and encourage financial institutions to treat people and businesses with similar financial and business profiles equally,” said Bostic, an economist who has extensively researched the CRA. “We must think carefully about how we create incentives to encourage the flow of capital to places where it adds the most value.”

Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic. Photo by David Fine

“Does that mean,” Bostic, continued, “an extra dollar where $1 million has been invested? Or is it an extra dollar where $1,000 has been invested?”

In that vein, the CRA might be strengthened by encouraging lenders to invest in largely overlooked places, as opposed to communities that are already improving in measures such as median household income, said Jessica Farr, a CRA subject matter expert in the Atlanta Fed’s Supervision, Regulation, and Credit Division. Places that are “moving up” have generally attracted more financing that helps meet CRA requirements than have places that are languishing, research by Bostic and others suggests.

“We need to think carefully about how to encourage revitalization in the communities where it’s needed and also focus on preventing displacement, and that’s very tricky,” Farr said.

Despite a surge in urban redevelopment, many LMI communities in rural areas are starved for investment. That contrast points up an inherent complexity in devising CRA rules that balance competing priorities.

This conundrum—how to encourage investments in LMI communities that do not ultimately push out the very people the CRA was conceived to benefit—is an example of where research and public comments can help refine the Fed’s proposed reform, said Farr, who worked closely with Fed Board of Governors staff on the proposal.

Encouraging investment in rural areas

The Fed document includes ideas aimed specifically at encouraging investment in rural areas. That too is a subject where feedback can help, Farr said. The CRA might be sharpened to better serve nonmetro areas by expanding the list of activities for which banks can get credit toward meeting their obligations. For instance, the refreshed CRA could broaden the type of organizations that banks can earn CRA credit for supporting in rural communities.

In addition, the Fed seeks to clarify the geographic areas where banks can receive consideration for CRA activities. Some financial institutions fund organizations that work across an entire state. But under the present CRA, a bank might have just two “assessment areas,” and banks often focus their activities in those two targeted zones to fulfill their CRA obligations. Farr said a refined CRA might reward banks for supporting community development work that benefits a broader region outside the prescribed assessment areas.

The Atlanta Fed’s Sixth District includes a great many small towns that attract scant capital, especially in impoverished regions like the Mississippi Delta and Appalachia. “I hope that by trying to clarify and broaden the geographic areas where banks can get CRA credit, we can encourage more investment in those areas,” Farr said.

A prominent challenge a renewed CRA could help confront is a nationwide dearth of affordable housing.

Indeed, a worsening nationwide affordable housing shortage highlights the importance of the CRA. The regulation encourages banks to finance critical community needs, such as building and preserving affordable housing. “With the demand for affordable units significantly exceeding supply, it is essential to strengthen the incentives for these loans and investments as part of CRA modernization,” Federal Reserve governor Lael Brainard said in an October 20 speech.

In particular, a more precise definition of affordable housing in the act might benefit LMI communities and financial institutions, Farr added. There is housing that needs preserving, such as “naturally occurring” affordable housing that is not subsidized, but banks may not be certain the regulators will give them CRA credit for financing such projects, Farr said.

Strengthening the CRA’s affordable housing provisions could help address severe gaps in home ownership. The ownership rate for Black Americans in 2019 was 42.1 percent, compared to 73.3 percent for white households, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey of March 2020. That gap has widened by 3.1 percentage points from a decade earlier.

Agencies still seeking consensus

Most financial institutions subject to CRA have gotten good marks. In 2019 and 2020 combined, more than 95 percent of institutions were rated “satisfactory” or outstanding, and a tiny handful were judged “needs to improve” or in “substantial noncompliance,” according to the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, a federal body that prescribes standards for financial regulatory agencies.

Like most federal financial regulations, Congress enacted the CRA statute, and then regulatory agencies crafted detailed rules to enforce it. The agencies update those rules and issue “guidance” as they deem appropriate.

Since the CRA’s inception, the three agencies have applied the same rules in their exams and prefer a unified approach to reforming the act, Farr explained—a goal that they have so far not achieved. The OCC adopted updated CRA rules in May that would take effect in 2023. However, the Fed and the FDIC did not adopt the OCC’s new rule. Nevertheless, the agencies aim to continue working toward consensus, Farr said.

By reflecting stakeholder views and providing an appropriately long period for public comment—through February 16, 2021—the Fed’s proposal helps build a foundation for a consistent approach to CRA modernization that has the broad support of both the banking industry and community organizations.

Find more information and submit comments here.