Special Report on Workforce Development

Despite a generally robust economy, skills training is critical amid long-term and cyclical labor force challenges

For years, Goodwill of North Georgia ran a successful program training unemployed and underemployed people in highway construction. That made sense: during the 1980s and '90s, metropolitan Atlanta added about 1,000 lane-miles of freeways.

When highway construction slowed, Goodwill shifted its training efforts toward general construction trades such as carpentry and electrical work. Again, that suited a market need until the number of housing units built in the metro area plummeted from about 75,000 a year to fewer than 7,500 amid the Great Recession. So, heeding advice from its business advisory council, Goodwill again adjusted, funneling clients into learning air-conditioning maintenance and other skills needed at apartment complexes, which after the recession increased as a share of the total number of housing units being built.

"By focusing on what was going on in the market, we were able to pivot," explained Jenny Taylor, vice president of career services at Goodwill of North Georgia. "Employers told us what was happening."

The experience of Goodwill underscores the rapidly changing demand for skills in the U.S. labor market and the related pressure those changing demands put on a fragmented network meant to prepare people for jobs.

This special report, part two of a four-part examination of issues surrounding economic mobility, focuses on workforce development: why it concerns the Federal Reserve and why it's important for everyone. This article explores the challenges involved in building an effective, cohesive system that improves economic opportunity, particularly for those who face the greatest difficulties in the labor market.

For an introduction to the series, see the Atlanta Fed's 2018 annual report, One Region. Many Economies.

Atlanta Fed's workforce work

The Atlanta Fed devotes considerable research and outreach to workforce development. Its Center for Workforce and Economic Opportunity focuses on labor market issues that affect low- and moderate-income individuals. The center serves as a hub for workforce information produced by the entire Federal Reserve System and regularly convenes experts and advises training practitioners. (See the accompanying video for stories of people who have benefited from workforce development, and for more on why the Fed cares about the subject.)

In some ways, it has rarely been easier to land a job in the United States. And yet it has perhaps never been more important to better prepare those seeking so-called middle-skill jobs. Middle-skill jobs are those that typically don't require a college degree but pay enough to support a family, roughly in the $35,000- to $60,000-a-year range. About 60 percent of all jobs in today's economy require some training or education beyond high school, compared to less than half that share in the middle 1970s, according to the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.

Skills shortages and a slow-growing labor force are big challenges

Two related features of the labor market pose increasing concerns for employers and job seekers.

First, fewer unemployed people means fewer job seekers chasing open positions (see chart 1). Since 2014, southeastern executives have reported trouble finding skilled workers in certain occupations, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta's Beige Book reports of economic conditions. In some fields, worker shortages could intensify. Between 2018 and 2028, 2.4 million manufacturing jobs could go unfilled, predicts a 2018 study from the consulting firm Deloitte and The Manufacturing Institute.

Second, the labor force participation rate has fallen from its 2000 peak. This decrease is associated with long-term structural changes in the labor market such as the aging population, the number of women joining the workforce leveling off, automation, and more people going to college rather than seeking jobs right out of high school.

Those factors mean slow labor force growth. Between 2010 and 2018, the U.S. civilian labor force added 8.2 million people, significantly smaller than the number added in any decade since the 1950s despite a steadily growing population, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (see chart 2).

Talent shortages and long-term declines in labor force participation mean that policymakers need to look beyond the traditional labor market pipeline to increase the supply of skilled workers—which is where workforce development comes in.

"Our 21st-century workforce development system must both improve economic opportunity, especially for those who face the greatest difficulties in the labor market, and meet the needs of businesses and society for a highly skilled and competitive workforce," said Raphael Bostic, president and chief executive officer of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

Workforce development challenges include lack of cohesion, funding

There's room to improve the workforce development system, which suffers from a lack of cohesion among training and education providers. In the metropolitan Atlanta area alone, for instance, a 2014 survey found more than 300 physical locations that play some role in workforce development. Many of the agencies reported little coordination with peers.

These times of economic and labor market upheaval, Bostic emphasized, demand a truly institutionalized workforce development system.

What's more, the financing of workforce development and training has changed. In 2017, the United States spent a smaller proportion of GDP on job training than all of its industrialized peers except Mexico, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. The federal government invested almost 0.25 percent of GDP on workforce development. By comparison, Germany spent 1.5 percent.

While federal spending on job training has declined, other sources of funding have increased. Pell Grants have expanded significantly and individuals, through loans and savings, invest heavily in their own education, sometimes taking on heavy debt. At the state level, efforts to make community college free, such as the Tennessee Promise, have closed some gaps in workforce system funding, though others remain, Bostic noted.

To be sure, employers spend billions of dollars annually on training, but most of that money goes to high-skilled workers with four-year college degrees. Moreover, employee participation in employer-sponsored training has been declining since 1996.

On top of the funding challenges, the return on investment could improve. A Cornell University study of 15 government-funded job training programs found that while the programs raised trainees' incomes, the gains averaged just $2,000 a year, still leaving many in economic hardship.

The workforce development community has spent years debating these challenges and done a lot of work to improve workforce development programs. "But the existing funding mechanisms, investment opportunities, and incentives in the workforce system are not truly supporting economic mobility, especially for low- and moderate-income populations," Bostic said.

Reaching those with barriers to boost economic mobility

Clearly, the reasons behind uneven labor market success are numerous and complicated. But these outcomes should not be predetermined by a person's socioeconomic background, gender, or race.

As Bostic has expressed, "There are many people in this country who really want to do great things. We should help them do it."

Just as important as helping individuals, perhaps, is the fact that bringing more people into the labor market benefits the macroeconomy and society as a whole, noted Paula Tkac, associate director of research at the Atlanta Fed. "When people go from unemployed to employed, we're all going to be better off," said Tkac. "They bring their technical skills, ideas, and talent to the marketplace, so there's more economic output being created."

Yet for some, bringing their talents to the marketplace is difficult. Barriers to the labor market include poor transportation, a lack of childcare, disability, military service, and past incarceration. For example, more than two-thirds of formerly incarcerated people were still unemployed or underemployed five years after their release, according to research from the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights in Oakland, California, cited in Investing in America's Workforce, a 2018 book of workforce research published by the Federal Reserve System, the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, and research centers at Rutgers University and the University of Texas.

One of the reasons Tkac serves on Goodwill of North Georgia's board of directors is because she values the organization's programs tailored to particular groups facing employment barriers.

The same obstacles to working can also thwart access to training programs. Bostic and Ann Carpenter of the Atlanta Fed's Community and Economic Development group have noted a serious problem in sprawling metropolitan areas with limited transportation options: the long distance that often separates affordable housing and the middle-skill jobs and training that low- and moderate-income people need.

In a chapter in Investing in America's Workforce, Bostic and Carpenter pointed out that in metropolitan Atlanta, 70 percent of training providers and coordinators say transportation is a barrier. "If many lower-income and lower-wage families have very limited access to both jobs and training to make them competitive for jobs, then the possibility of economic mobility must be quite small," Bostic and Carpenter wrote.

Career pathways are key

Another key to addressing economic mobility concerns is to set job seekers on a path to a career, not simply to prepare them for an entry-level position. Up until the early 2000s, in fact, Goodwill of North Georgia focused mostly on placing people in jobs in "the four F's": food, folding, filth, and flowers—that is food service, laundry, cleaning, and landscaping.

Taylor explained that Goodwill does not want simply to create lots of working poor. To that end, the organization tracks the percentage of workers it places in working- to middle-class jobs. Over the past five years, that share has climbed from 14 percent to 25 percent, Taylor said.

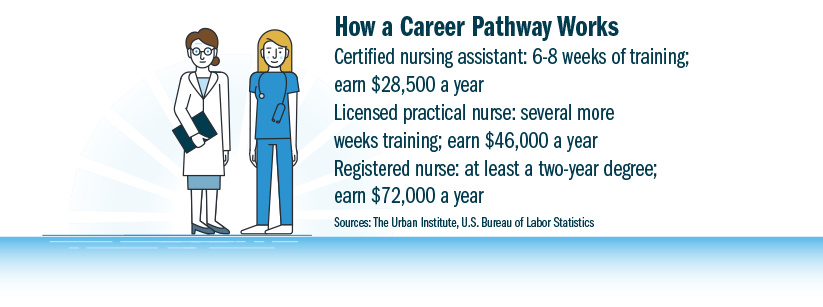

Health care services is a good example of a field that offers career pathways. Certification as a nursing assistant requires six to eight weeks of training, and the work pays about $12 an hour. From there, the pathway goes to licensed practical nurse, which requires another several weeks of training. Median pay for a licensed practical nurse was $46,240 in 2018, nearly $20,000 more than the median for a certified nursing assistant, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Registered nurses, who must have at least a two-year associate's degree, earn substantially more.

One of the obstacles to career pathways are "benefits cliffs," the scenario when means-tested public supports fall sharply, or off a cliff, as recipients earn more by working more hours or securing promotions by learning new skills. Basically, these benefits cliffs result in penalties that are, effectively, high marginal tax rates for the least wealthy: when low earners' pay inches up, they may wind up worse off. Understanding benefits cliffs, and thus informing policies and programs to confront them, is a major focus of the Atlanta Fed's workforce development efforts.

Birmingham faces up to workforce challenges

In Birmingham, Alabama, both the problems and the promise of workforce development are evident. Anoop Mishra is the regional executive at the Atlanta Fed's Birmingham Branch. A Birmingham native whose job is to stay in touch with the state's business and community decision makers, Mishra said the city has yet to establish a singular economic identity decades removed from the dominance of the steel industry.

Although health care has helped fill the void left by the decline of iron and steel, that sector is challenging, Mishra noted, not least from a workforce perspective as the industry faces continual shortages of nurses and other workers.

While health care and, to a lesser degree, finance have boosted Birmingham, employment and economic growth remain disproportionately linked to low-skilled jobs and localized industries that don't attract talent or dollars from outside, according to Building It Together, a 2018 report on aligning education and jobs in greater Birmingham. Birmingham, with its scattered workforce development efforts, has lagged most southeastern metros in key economic growth metrics in recent decades.

However, the Building It Together report demonstrates that Birmingham is facing its challenges, Mishra said. Local leaders are formulating programs to address workforce development concerns, including efforts to train workers for the nearby automotive assembly and supply plants and to educate parents and teachers about the opportunities for middle-class wages in advanced manufacturing.

"We have a lot of potential," Mishra said. "There is a clear goal, and strategies and infrastructure are starting to come together to think through these efforts."

Aligning training with industry needs is crucial

Central Six AlabamaWorks is a key part of those efforts.

Aligning training with employers' current and future needs is essential to crafting effective programs. The Birmingham-based Central Six assembles clusters of companies and training providers focused on particular occupational sectors or industries, explained Antiqua Cleggett, executive director of Central Six AlabamaWorks. (You can see Cleggett discussing Central Six's work in the accompanying video.)

These "sector partnerships" have recently gained favor in the workforce field. Central Six's manufacturing partnership, for example, includes 38 companies. Central Six regularly surveys those firms to learn their most pressing workforce needs, information passed along to training agencies to help them tailor programs to meet manufacturers' talent gaps.

Recently, for example, the manufacturing partnership noted that several employers needed to train existing employees in hydraulics to operate industrial robots. So Central Six helped devise a five-week hydraulics and pneumatics curriculum.

"With sector partnerships, you've got a more unified voice that's going after very specific challenges," Cleggett said. "It's an advantage all the way around."

That type of thinking can shape workforce development systems to meet the stiff challenges of the 21st-century economy. After all, two of the basic ingredients of economic expansion are increasing both the number of workers and their productivity. Effective workforce development can help accomplish both.