A couple of years ago, officials in Heflin, Alabama, canvassed their county’s 15,000 residents about their public policy concerns.

One issue consistently arose: a lack of internet access. “That’s no different from anywhere else in rural America,” said Tanya Maloney, director of economic development in Heflin, seat of Cleburne County.

Among more than 1,000 people who answered Maloney’s survey, not one said they were happy with their online service. Cleburne County (pronounced clee-burn) straddles Interstate 20 on the Georgia border, sprawling over an area nearly twice the land mass of New York City.

Unlike New York or any major city, though, only 13 percent of Cleburne County residents have ready access to fixed high-speed broadband service, defined by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) as 25 megabits per second (Mbps) download speed and 3 Mbps upload speed, according to the FCC’s 2019 Broadband Deployment Report. By comparison, 86 percent of all Alabamians and 94 percent of Americans live in places with broadband access.

Cleburne County is hardly exceptional. Rural counties across the nation and Southeast are far less wired than densely populated places. Across the states of the Sixth Federal Reserve District—Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee—1.2 million people live in counties where less than half the population is within reach of basic fixed broadband service, according to the FCC report (see the map).

Digital inclusion equals economic inclusion

It’s about more than streaming movies. Broadband access is widely considered a ticket to the modern economy and society. “Digital inclusion means economic inclusion,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City researchers Jeremy Hegle and Jennifer Wilding wrote in a July 2019 report. “For rural areas today, broadband is a utility as vital as electricity and telephone service.” It “should be unacceptable” that millions of American households lack broadband subscriptions, Adie Tomer and Lara Fishbane of the Brookings Institution wrote in a 2018 paper.

Limited broadband access, according to research, hinders consumers and communities in critical pursuits including health care, education, job hunting, economic development, agricultural practices, and emergency services. Anecdotes of high school students crowding fast food restaurant parking lots to tap free wifi are common. As students get online in late afternoons, many rural communities see their already sluggish internet speeds slow to a virtual crawl.

Measurements vary of the so-called digital divide between metro and rural areas. But the contours are well-established. Broadband reaches about 98 percent of metropolitan residents nationally and in the Southeast. According to the FCC, 74 percent of the nation’s rural population has broadband access, but some research suggests that the actual share is lower. More than 20 million Americans in rural and urban areas alike lack sufficient access to high-speed broadband, according to research by Jordana Barton at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. Some research puts the number of Americans who can’t buy broadband service at more than double the FCC’s February 2020 estimate of 18.3 million.

In metro areas, obstacles to broadband access are generally economic—low- to moderate-income families often can’t afford it. Among major cities in the Southeast, the biggest gaps in broadband usage are in Miami, Birmingham, and New Orleans, where a third to 36 percent of households lack a broadband subscription despite its availability, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2018 American Community Survey.

Creating broadband access—building the infrastructure—is the first leg in Barton’s “three-legged stool” necessary to address the digital divide. The other two legs are access to a computer and, third, training and technical assistance. The second two, Barton points out, are ineffective without the broadband infrastructure.

In December 2019, Sonny Perdue, secretary of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, announced that his department will make available $550 million in ReConnect funding in 2020. Photo courtesy of the Hamilton, Alabama, Journal Record

Coronavirus shutdowns intensify need for broadband

The metro-rural digital divide has received considerable attention and investment in recent years. Then in early 2020, widespread work-at-home programs and school closures amid the coronavirus pandemic brought into stark relief just how crucial it is for households to be wired.

FCC commissioner Geoffrey Starks wrote in The New York Times in March, “When public health requires social distancing and even quarantine, closing the digital divide becomes central to our safety and economic security.” Congressman Robert Aderholt (R-Ala.) also wrote in the Washington, DC newspaper The Hill that if the pandemic leaves schools closed through the end of the academic year, an unfolding reality as of this writing, rural students will “fall woefully behind” their metro counterparts.

Aderholt was among those arguing to include funds for broadband deployment in economic relief proposals during the pandemic. One bill introduced during the pandemic, for instance, would permit using money from an FCC program to install wifi hot spots in school buses to expand access in rural areas once the pandemic is over and buses are running again.

Even before the public health crisis, subpar internet service was an issue the Atlanta Fed’s community and economic development (CED) researchers had begun to study more closely.

Heightened attention to the problem from states and the federal government, via the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) revamped ReConnect program, for instance, helped bring the metro-rural digital divide to the center of the Reserve Bank’s attention. Amid this convergence of interest, the Atlanta Fed’s CED group set out to help commercial banks understand how they can support efforts to improve broadband access, explained Sameera Fazili, director of engagement for the CED.

Sameera Fazili. Photo by David Fine

To that end, the Atlanta Fed, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation launched a series of events with lenders in the Southeast. A key to these efforts is the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA).

The CRA encourages banks to provide services to communities where they have a presence, including low- to moderate-income communities. CRA guidelines include broadband as a form of infrastructure investment and essential community service, so lending for broadband construction in underserved areas can help banks meet their CRA requirements. This aspect of the CRA’s mandate means the act can play an important part in closing the digital divide while helping financial institutions and improving economic stability, according to Barton.

For its part, the FCC has declared “closing the digital divide … its top priority.” Yet the divide persists, particularly in rural America.

Same economic problem as rural electrification

The main cause of the metro-rural digital divide is rooted in economics. It is simply not profitable to extend costly infrastructure to small, dispersed populations. Consider that Fulton County, Georgia, home to Atlanta, offers a market of more than a million people in an area roughly the size of Cleburne County.

The same economic dynamic kept swaths of rural America in the dark until the 1940s and ’50s, when the New Deal’s Rural Electrification Administration brought electricity to the nation’s hinterlands. Rural electrification was a major thrust of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s sweeping program that helped lift the nation out of the Great Depression.

Can Fast Internet Service Revive a Rural Economy? Northwest Alabama Will Find Out

First, do no further harm.

Tombigbee Electric Cooperative received $29 million in grants and loans from the USDA ReConnect program in 2019. Chief executive Steve Foshee speaks at a celebration of the award. Photo courtesy of the Hamilton, Alabama, Journal Record

That’s how Steve Foshee views the promise of the fiber optic network he is building in economically challenged northwest Alabama.

“You gotta stop the bleeding before you can start growing,” Foshee said.

Foshee is the chief executive officer of a rural electric cooperative that plans to invest up to $80 million—more than quadruple its annual revenue—to deliver high-speed internet service to a thinly populated, hilly locale that has shed a good deal of economic blood.

The three counties making up Tombigbee Electric Cooperative’s core service area are home to 60,000 people in an area nearly twice the size of Rhode Island—which has a population over 1 million. The combined population of the three counties has fallen by 10,000 since Tombigbee opened in 1941. Total employment has declined 20 percent since the mid-1990s, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

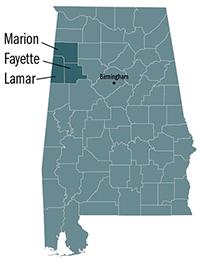

Drawing on loans, grants, and its own funding, Tombigbee aims to bring its members an essential utility of modern life, just as the nonprofit introduced electricity seven decades ago. Among the three counties Tombigbee serves—Fayette, Lamar, and Marion—none has broadband service available to even half its residents, according to Federal Communications Commission data. (Tombigbee’s fiber network will extend into parts of three additional counties as well.) By comparison, broadband service is within reach of 86 percent of all Alabamians, FCC data say.

Today, the three-county area’s biggest export, Foshee said, is bright kids who flock to Birmingham, Huntsville, and Atlanta. He and other local leaders hope broadband service will stem population and job losses, and perhaps it will. A class of high school seniors to a person told Foshee they would consider returning after college if high-speed internet were available, he said.

Moreover, Tombigbee’s first phase of the fiber rollout—to 5,500 homes and businesses—saved 1,500 jobs that would have left without broadband, according to Tombigbee’s research.

Consider the bleeding slowed, at least.

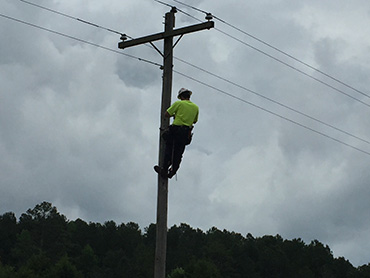

Tombigbee Electric Cooperative is building a network to deliver broadband services to 25,000 homes and businesses in rural northwest Alabama. Photo courtesy of Tombigbee Electric Cooperative

Tombigbee’s service area typifies both the “digital divide” and broader economic disparities between rural and metropolitan places. The electric co-op’s broadband effort is among numerous such projects nationwide that, taken together, have produced mixed results.

Through a subsidiary called Freedom Fiber, Tombigbee aims to extend 2,000 miles of fiber-optic cable to about 25,000 homes and businesses. Freedom will attach 80 percent of the cable to Tombigbee’s existing power poles, which is far less expensive than burying the wire.

Foshee views broadband as essential to bolster four elements of community well-being: education, health care, economic development, and quality of life. And although all four are critical, area banker Brad Bolton figures scant broadband availability is especially damaging to economic development and education. Bolton, president and chief executive officer of Community Spirit Bank in Red Bay, Alabama, said high-speed internet service is a basic requirement for firms shopping for locations.

He also believes broadband access can close a rural-metro educational opportunity gap. “Kids in Huntsville can go home and get online and do whatever they want,” Bolton said of the city a two-hour drive from Red Bay. “These kids in our areas…don’t have that accessibility at home unless they get on their mobile devices, and cell phone service is spotty as well.” Widespread school closings during the coronavirus pandemic heightened the urgency of wiring rural homes.

Foshee figures Tombigbee has an obligation to wire its communities. If the coop doesn’t do it, he says, nobody will. “Watching a Netflix movie is going to be important, but we’ve got to do a lot more than that if we’re going to change rural America,” he said. “Somehow a community’s got to figure this out.”

Extending broadband service has not engendered the same urgency as rural electrification did. Nevertheless, governments have expended considerable resources on under-wired places. Between 2010 and 2017, the FCC and the USDA invested roughly $40 billion in loans and grants to rural broadband providers—telecommunications firms, nonprofit electric cooperatives, and municipalities. That investment includes $577 million through 159 awards in states in the Atlanta Fed’s district.

The federal outlays generally require recipients to invest matching funds. The USDA’s rural development unit committed $506 million to broadband projects in fiscal year 2017, which spurred $254 million in private-sector commitments, according to the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), a unit of the U.S. Commerce Department.

In addition to federal programs, most states have instituted broadband deployment initiatives targeting rural communities (see the sidebar).

The State of State Rural Broadband Efforts

States in the Southeast have launched study groups, task forces, and other efforts to encourage carriers to extend broadband service into rural areas. High among these efforts’ goals is offsetting the capital investment required to deploy broadband to unserved areas.

• Alabama’s legislature has allotted

$7.4 million for grants, according to the

Alabama Broadband Accessibility Act 2018–2019 Program

Year Report, the latest on the state’s website. The report lists 22

broadband construction projects—serving a combined

potential customer base of 19,000—that have received state

grants. State grants are intended to fund no more than 20

percent of a project’s total cost.

• Florida’s legislature initiated a

broadband program in 2009. However, Florida now has no

state-level broadband office, program, or funding source,

according to a January 2020

Florida Senate report. However, Florida might have comparatively little need for a

rural broadband program. It is among the better-wired states

generally, according to most measures, and rural residents make

up a far smaller share than in any other state in the Sixth

District—about 9 percent.

• Georgia’s legislature created the

Georgia Broadband Deployment Initiative in 2018 to coordinate

efforts to wire the 1.6 million Georgians who lack broadband

access, according to

the program’s plan. Initiative leaders are devising a map to show whether every

address in the state has access to broadband service, the plan

says. Officials are collecting address data from local

governments, property appraisers, emergency 911 coordinators,

and power companies. Also, the state passed a law in 2019

allowing 41 nonprofit electric membership cooperatives and four

telephone co-ops to offer broadband service in their markets.

• Louisiana governor John Bel Edwards

signed an executive order in August 2019 creating the

Broadband for Everyone in Louisiana Commission. The group aims to “facilitate” private sector

carriers, public utilities, and others to extend basic broadband

service to everyone in the state by 2029. The commission is

gathering information and assembling detailed maps to identify

the most underserved areas.

• A

2019 law

allows Mississippi's 25 electric cooperatives

to sell broadband service, and several co-ops have announced

plans to do so. Those co-ops likely will seek federal grants or

loans, as the projects represent substantial investments for

small rural electric providers. For example, Tombigbee Electric

Power Association in Tupelo said it expects to spend $95 million

to build a broadband fiber optic network to serve 15,000

customers across eight counties in northeast Mississippi.

• The

Tennessee Broadband Accessibility Act

of 2017 inaugurated one of the region’s more financially

aggressive state broadband expansion programs. The

Tennessee legislature has committed an

aggregate $45 million for grants over three fiscal years from

2018 through 2020. Tennessee’s approach targets areas not

included in federal broadband efforts, according to documents

describing the state’s plans.

Clearly, the public sector has committed resources to extend broadband access, and that investment has spurred additional spending. But extending broadband to all corners of America will require significant ongoing investment. The state of Georgia alone estimates that it will require more than $1 billion to bring broadband to its unserved areas.

So far, federal efforts to boost rural broadband access have shown mixed results. For example, post–Great Recession stimulus efforts included a USDA initiative intended to extend broadband to 7 million new users, mainly in rural areas. But the program brought only about 750,000 subscribers online, according to a 2014 Government Accountability Office report.

“In the past five years, there’s been more than $22 billion in subsidies and grants to carriers to sustain, extend and improve broadband in rural America. But adoption has barely budged,” Microsoft researchers wrote in a 2019 study.

One of the main reasons progress has lagged is because of inadequate FCC mapping of which locations have broadband access, Microsoft’s researchers note in a common criticism. The FCC’s national maps are not nearly as detailed as one Georgia officials are compiling as part of a broadband deployment Initiative. The state’s plan refers to known shortcomings in the FCC’s data.

In fact, the FCC’s mapping is itself an often-cited problem. The FCC considers a subunit of a census tract (called a census block) “served” if a single household or business has access to broadband service. Overstated broadband availability data could limit funding eligibility, a problem most likely to affect geographically large rural census blocks with sparse populations and the biggest funding needs, according to the American Broadband Initiative 2019 Milestones Report from the NTIA.

Other researchers point to complex lending processes at the USDA. Some federal grant and loan programs, research shows, have allowed affluent metro areas to secure funding meant to target underserved rural areas. In a 2019 paper, University of Virginia researchers Christopher Ali and Mark Duemmel argue that the USDA’s Rural Utilities Service needs to clarify its role in extending broadband. The agency, the researchers write, acts as bank, advocate, regulator, and champion, diffusing energy and effort and hampering its effectiveness.

An outlook not entirely bleak

Despite challenges and concerns, the news on broadband service and adoption is not all bad.

Many states are stepping up their efforts to spread broadband service. Though the FCC data are broadly questioned, recent statistics paint a general picture of a digital divide that, while wide in some ways, appears to be narrowing. And better maps might be coming from the FCC. The commission is evaluating ways to collect more precise broadband deployment information, according to the NTIA. Further, the U.S. Congress passed legislation in March directing the FCC to compile more detailed broadband access maps. The bill was awaiting the president’s signature at publication time.

Meanwhile, average fixed download speeds in the U.S. increased 34 percent from 2016 to 2017, moving the country from 11th to fifth in the world, according to the FCC.

Heflin optimistic about broadband’s promise

Back in Heflin, things are looking up. The U.S. arm of an Australian firm, Gigafy, is stitching together a system of microwave towers and fiber optic cable to deliver service to Heflin residents and businesses for around $65 a month. Thus, Heflin appears to be gaining the critical first leg of Barton’s stool that undergirds effective broadband adoption.

Gigafy has wired Heflin’s city hall and a few downtown businesses, and early reviews are enthusiastic. Maloney, the town’s economic development director, said her brother-in-law’s film company can upload a video in nine minutes, down from nine hours using Heflin’s previous internet service.

“I think this opens a huge market for us to advertise as a community to live in,” Maloney said. “Our location is halfway between Birmingham and Atlanta. Somebody could live here, commute if necessary, and have the charms of rural life and access to great internet service.”