Today’s world is a vast laboratory for people who study economic uncertainty, including a group at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

For the Bank’s researchers, the pandemic-induced crisis has supercharged every one of their time-tested measurements of uncertainty as they attempt to separate signal from noise in disagreements among economic forecasters, measures drawn from media reports and social media, and surveys of business executives, In fact, muddled economic circumstances provide ample opportunity for Atlanta Fed economist Brent Meyer and colleagues to gain important new insights from the Bank’s Survey of Business Uncertainty (SBU) about where individual firms and, in turn, the broader economy, may be heading. Crucially, the six-year-old SBU has been around long enough to produce rich data, Meyer said.

The Atlanta Fed’s Brent Meyer. Photo by David Fine

He and his cohorts have analyzed enough responses to conclude that firms’ reported expectations about revenues and hiring generally are accurate. In other words, companies are doing what they say they’ll do. These “forward-looking” measurements of uncertainty are new, so the researchers from the Atlanta Fed—along with SBU colleagues at the University of Chicago and Stanford University—are blazing paths in the relatively young field of economic uncertainty studies. (In 1983, former Fed chair Ben Bernanke published one of the first attempts to rigorously model the effects of uncertainty on business investment.)

The importance of looking ahead

These surveys of expectations are valuable for measuring what firms’ managers perceive in real time.

An ability to look toward the horizon is proving especially useful now. The economic earthquake of 2020 was so abrupt and powerful that backward-looking uncertainty measures contribute little to shaping policy responses, as Meyer and a team of coauthors explain in a new research paper. “The speed and scale of the COVID-19 employment shock dwarf any previous shock in the modern era,” wrote Dave Altig, Atlanta Fed research director; Scott Brent Baker; Jose Maria Barrero; Nick Bloom; Phil Bunn; Scarlet Chen; Steven J. Davis; Meyer; Emil Mihaylov; Paul Mizen; Nick Parker, Atlanta Fed survey director; Thomas Renault; Pawel Smietanka; and Greg Thwaites.

“These are really novel things that we’re doing,” Meyer said in an interview. “We’re eliciting expectations from firms that we think they will act on. Uncertainty about revenue over the next year tells a lot about their expansion plans, hiring, capital expenditures. These are novel findings, and we anticipate they will be very useful once we feed them directly into macro modeling frameworks.”

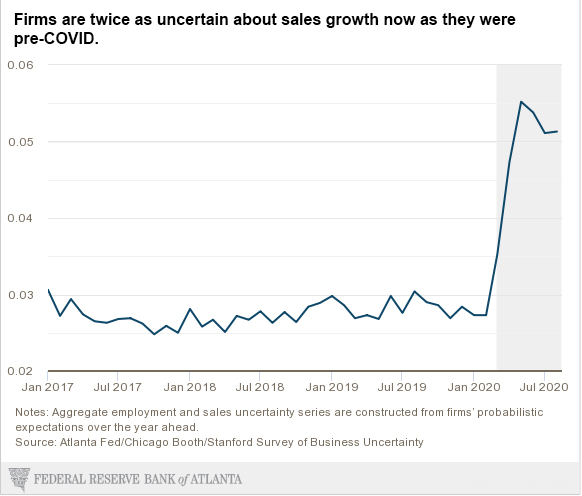

In other words, an important next step is to incorporate the survey findings into formulas that predict the direction of the macroeconomy. It’s important to note that the value in the survey responses comes from what firms’ decision makers say about their own companies, which they control, Meyer points out (see the chart). Executives’ thoughts about broader economic uncertainty are less useful.

Survey responses during the summer do not tell of a rapid rebound in sales, expansion, or hiring, Meyer said. Aggregate expectations of sales growth over the next 12 months have recently plummeted to a range of 1 percent to 1.5 percent from about 4.5 percent before the pandemic. Moreover, most companies in the SBU and other Atlanta Fed surveys expect their employment to remain below prepandemic levels through at least the end of 2021.

Of course, whether we’ve already seen the worst of the pandemic downturn is a great unknown. Other unknowns—such as the future spread of the virus, mitigation measures, and their implications—are “still hanging like a cloud over these firms, and it’s depressing their expectations,” Meyer said.

As the authors wrote: “Given the scale of recent job losses and the collapse in investment, a strong, rapid recovery would require a huge surge in new activity, which unprecedented levels of uncertainty will discourage.”

Uncertainty could mean a reshuffling

Companies of all sizes in nearly every industry are feeling uncertain, not just those like accommodations and travel that are especially vulnerable to the pandemic-induced recession. Such record-high uncertainty readings suggest that the pandemic’s shock could exert change on the economy well after the crisis passes, Meyer said.

For example, Atlanta Fed surveys have found that remote working could triple even after pandemic-related workplace safeguards end, which would represent a change with broad economic ripples. Firms also figure to slash business travel spending by nearly 30 percent and increase the online share of meetings with external parties—such as clients, suppliers, and medical patients—from less than a fifth to about half.

Some companies probably won’t welcome such fundamental shifts in how business is conducted, but businesses that cater to people spending more time at home could benefit. For the macroeconomy, these shifts could spell a lengthy and painful transition, Meyer explained. One big reason: it takes a long time for people to learn new skills and switch from jobs in, for instance, commercial real estate or the lodging industry to an occupation involved in telemedicine, as recent research by Chicago Fed economist Joel David explores.

What economists term a reallocation of resources across the economy also happened after the Great Recession, when the large reshuffling of jobs it brought likely helps explain sluggish employment growth afterward. Some research does, in fact, show that the economy reallocated jobs at a much slower pace during the recent recovery than it had 20 or even 10 years earlier. It appears that unfortunate trend may well continue, in part because of the very uncertainty that the Atlanta Fed is intently studying.