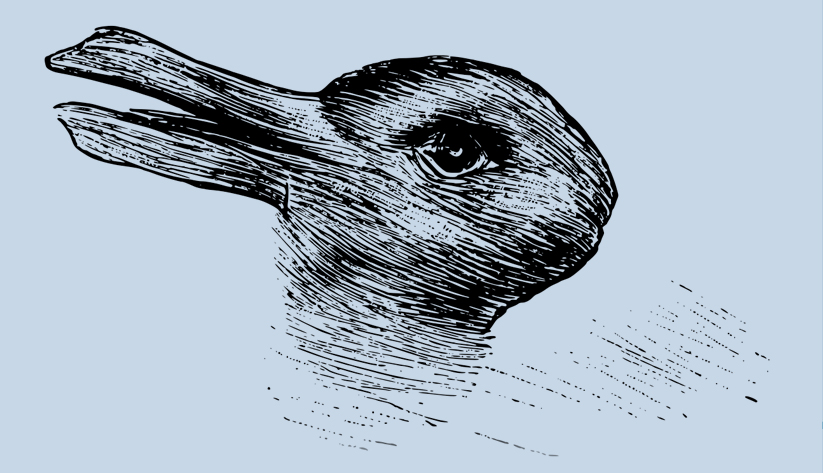

Do you see a drawing of a rabbit or a duck? Looking at the same image but seeing it differently is what the coauthors realized was at the heart of their problem.

Do you see a drawing of a rabbit or a duck? Looking at the same image but seeing it differently is what the coauthors realized was at the heart of their problem.The global pandemic has shined a light on two scientific fields whose practitioners have not generally collaborated much: economics and epidemiology. Economics has been prominent because the pandemic has upended economies the world over, and epidemiology because an infectious disease has spread quickly and caused millions of deaths.

Typically, economists and epidemiologists advance their careers based on their standing with others in their own fields, said Atlanta Fed economist Karen Kopecky and Johns Hopkins University epidemiologist David Dowdy. This dynamic has usually meant epidemiologists and economists produce research targeting their peers. And so it was with the COVID-19 pandemic. But a small group recently sought to change this relationship, coming together to begin bridging the gap between the two.

Kopecky, who has researched various aspects of health-related economics, and Dowdy are among 11 participants in the project that produced the working paper titled "Modeling to Inform Economy-Wide Pandemic Policy: Bringing Epidemiologists and Economists Together."

Sparking a change in thinking

Kopecky said the collaboration with infectious disease experts challenged her normal mode of thinking about problems. “It tends to spark creativity,” Kopecky said of working across the intellectual aisle.

The Atlanta Fed’s Karen Kopecky. Photo by David Fine

Teaming with epidemiologists, she said, showed her that her default way of thinking about an issue does not always align with the perspective of other experts who are also painstaking in their work and even use similar mathematical models. Kopecky said the work helped her understand she needs to communicate about her work more clearly. "Sometimes I don’t realize just how poorly I explain myself to noneconomists," she said.

The crux of the differences between the two groups is that epidemiologists do not think first about tradeoffs in the way economists do, whereas economists do not think first about making their models representative of disease trends over time. Disease experts view effects on health to be the most important thing about shifts in human behavior (in short, something limiting the spread of disease is a good thing).

On the other hand, economists typically emphasize tradeoffs between health and wealth. For example, if restaurants limit dining capacity to 50 percent, how much does public health benefit compared with the loss of jobs and income? Economic models tend not to focus to the same degree as epidemiological models on the intricacies of disease transmission. Instead, they make simpler assumptions about the effects of limitations on the spread of disease.

Both approaches have real merit. But the differing perspectives can seem contradictory, according to the group from the Atlanta Fed, Johns Hopkins, and the University of North Carolina.

Most importantly, clashing perspectives can lead to conflicting policy recommendations. As the resulting working paper put it, "In today’s highly polarized environment, when even scientifically grounded ways out of the crisis (such as scale-up of highly effective vaccines) are called into question, lack of consensus leads to confusion at best and exploitation of scientific findings at worst."

Traditionally separate sandboxes

Because such cross-disciplinary projects among these two groups are rare, neither Kopecky nor Dowdy had worked deeply with counterparts from the other camp.

"There was never the motivation to collaborate, so we all grew up in our own silos," Dowdy said. "So when the time came and we needed to (collaborate), we didn’t know how."

Johns Hopkins University’s David Dowdy. Photo courtesy of Johns Hopkins University

The group didn’t assemble only to write the article. The effort’s larger goal is to promote ongoing collaboration and ultimately produce "a more fully informed view, and to arrive at a set of conclusions that both groups can comfortably accept," the coauthors wrote.

The paper lays out an approach to future collaborative research and policy analysis that the group calls an "urgent priority" before a future pandemic. The recommendations include inspecting each other's models, learning the other camp's language, and harmonizing messages so policymakers get nuanced, expert advice that balances the perspectives of epidemiologists and economists.

At least among the participants in this project, there are hopeful signs. Dowdy said that the half-dozen members of the group of economists and epidemiologists who work at Johns Hopkins, some of whom he did not know before this undertaking, will likely partner on further research. They have already formulated proposals for grant funding.

Meanwhile, Kopecky has begun talking with a group of research engineers who are applying for funding to build pandemic models for the Centers for Disease Control. Those scientists, from North Carolina State University, contacted her after reading the paper, she said.

Rabbit? Duck? It's both

Epidemiologists study the transmission of disease and how to slow or halt that transmission. Economists, of course, study the economy. In the context of the coronavirus pandemic, economists have focused on complex interactions among economic machinery like supply chains and consumer behavior in the face of sickness, deaths, and restrictions designed to lessen the impact of the disease.

Economists and epidemiologists alike meticulously craft mathematical models to try and predict behavior in response to events. But the two groups tend to focus on different variables and outcomes.

As the paper puts it, epidemiologic models generally are meant to generate understanding about health outcomes. Economists want to untangle economic implications and drivers of behavioral change more than furthering their understanding of health outcomes.

For example, the paper describes two studies from 2020 that used almost identical data from mobile phones to examine restrictions on mobility. One study took an epidemiological approach, weighing how much the number of infections could be cut by limiting mobility by 50 percent or 75 percent. This analysis did not account for considerations such as the cost of these hypothetical restrictions, and whether their benefit would justify those costs.

The economic study, by contrast, aimed at determining which kinds of businesses could be shut down to inflict the least economic harm. Yet the economic research did not explore how much each type of business might contribute to the spread of COVID-19.

Dowdy compares the differing viewpoints to a sketch that philosophers use to illustrate a concept called "aspect perception." To some, the drawing looks like a duck. However, others can just as easily view it as a rabbit. Particularly in a crisis, policymakers need to see and understand both the rabbit and the duck, and a collaborative effort across disciplines can help make that happen.