The accelerating pace of development in the field of generative artificial intelligence (AI) underscores the shortage of high-tech workers in the United States.

Long discussed, the dearth of specialists in AI and other information technology sectors gained prominence when the White House referenced it in a 2023 executive order. One part of the order called for educating US workers in AI and other high-tech skills. Another called for possibly enhancing the H-1B visa program for experts in AI and "other critical and emerging technologies," to enable more foreign workers and their immediate families to enter the country and legally remain as permanent residents.

The Atlanta Fed's Federico Mandelman

The Atlanta Fed's Federico Mandelman

Atlanta Fed research adds to the conversation of potential policy changes in the H-1B visa program. The goal is to improve the productivity of the tech sector, which makes up a major portion of the nation's economy.

In an Atlanta Fed working paper, "Skilled Immigration Frictions as a Barrier for Young Firms," researchers found that H-1B visa regulations impede young firms from hiring highly skilled foreign workers and constrain the production of new technology and job creation for US workers and foreign nationals.

The researchers found these constraints represent a potential opportunity cost that may drag on the economy. The regulations also encourage foreign workers to bypass jobs with start-up firms to take positions with established tech firms. Finally, the survival rate of young tech firms has declined as the number of H-1B visas has stayed the same for nearly two decades. Incumbent firms hiring a lion's share of visa holders represent a growing proportion of the tech sector.

Atlanta Fed research economist Federico Mandelman said this research is notable for its exploration of the effects of current H-1B policy frictions on younger firms and future innovation. The paper, which Mandelman coauthored with Mishita Mehra of the University of Richmond and Hewei Shen of the University of Oklahoma, continues Mandelman's examinations of international macroeconomics.

Congress established the H-1B visa in 1990 to authorize US employers to temporarily hire foreign nationals for jobs that require specialized knowledge and a college education. Categories include engineering, science, math, medicine, theology, and the arts.

Mandelman said the reasons young tech firms cannot hire enough skilled workers start with a shortage of skilled domestic high-tech workers. One solution available to companies is to hire skilled high-tech workers from other countries and help them get an H-1B visa to enter the United States, but competition for those workers is intense. Some employers gamed the H-1B visa system after a rule change in 2019, filing multiple applications for workers in hopes of boosting the chances their registrants would win the random lottery for the visas, according to the Department of Homeland Security.

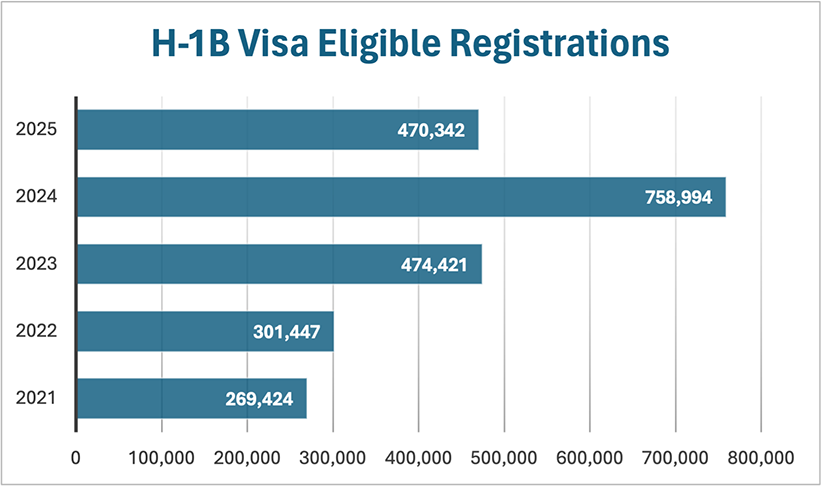

The rules were tightened for 2025, the current fiscal year, but nearly a half-million eligible registrations were submitted for the 85,000 H-1B visas approved by Congress, the same number since 2006.

Source: US Department of Homeland Security

Skilled foreign workers tend to seek out jobs with big global tech firms rather than start-ups, Mandelman said.

"If you're hired by a multinational big-tech company, you can lose the lottery but still be employed in an affiliate in London or Singapore, work remotely, and—if needed—reapply next year for an H-1B visa," Mandelman said. "Start-ups usually require highly specialized skills and can't locate workers overseas. Hiring their best option is complicated amid labor shortages in the US labor market."

Samantha Rose-Sinclair, talent connect manager at the Georgia Institute of Technology's Advanced Technology Development Center (ATDC), is familiar with the situation Mandelman described and echoed his concerns about the effect this trend will have on the tech industry's future.

"When I speak with international students at Georgia Tech career fairs looking for opportunities with ATDC's portfolio of start-up companies, the question of the forefront of the conversation is, understandably, whether start-ups can sponsor their workers," Rose-Sinclair said. "In that regard, start-ups face additional hurdles when tapping into a wealth of talented international students, not just as potential sponsored employees, but earlier on in [the choice of internships that affect] the progression of their career exploration as well."

Rose-Sinclair also expressed concern about the possible opportunity cost of talented foreign tech workers going to work for incumbent technology firms.

"While I engage in conversations with international students about our start-ups' ability to sponsor, what concerns me is the conversations I don't get to have—as in, the international students and job-seeking immigrants who may discount start-up companies as a whole under the expectation that they're generally unable to sponsor work visas and pursue opportunities at large companies exclusively. In that sense, again, start-ups aren't connecting with these students and job seekers who would otherwise bring critical specialized skills to their companies and the ecosystem," she said.

As Mandelman pondered the long-term consequences of immigration policies on high-tech start-ups, he said innovation may suffer.

"Growth is in start-ups," Mandelman said. "Facebook and Apple are on the frontier but think about the next 20 to 30 years. We want start-ups today that will be the Facebook and Apple of the future, and yet it is very difficult for these young firms to find workers."