Distant, complex forces clobbered the economy, and no one knew how long the shock would last. To prevent a rash of bank failures and even wider economic damage, a central bank launched an infusion of credit on generous terms.

The banks that benefited welcomed the help, but this action ignited a spirited debate—not least within the central bank itself—over whether this was an appropriate policy response to a devastating but likely temporary emergency.

This scenario is not pulled from headlines describing Fed actions amid the coronavirus pandemic or Great Recession. This drama unfolded 100 years ago, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta was smack in the middle of it. Yet as Atlanta Fed economist and policy adviser William Roberds noted, "The issues remain live. The question is, are you bailing out unlucky people, or is this actually for some public purpose?"

In other words, does central bank lending at low interest rates serve the public good by thwarting a contagion that could undercut the entire economy? Or does opening the credit spigot reward excessive risk-taking and undermine the central bank's credibility?

The Atlanta Fed's Will Roberds.

Photo by David Fine.

In a new article in the Atlanta Fed's Policy Hub, Roberds and noted central banking historian Eugene White explore an episode from 1920 that featured one of the first examples of the Federal Reserve acting as a lender of last resort (which means the Fed steps in to limit a financial emergency when no one else can or will). The controversy then stemmed from the fact that the U.S. central bank—barely seven years old at the time—had no formal authority to play such a role, but the Atlanta Fed and its leader, Max Wellborn, pushed ahead to save the region's "cotton banks" anyway.

What factors prompted the Fed's intervention?

That year, economic weakness in the United States and Europe sapped demand for cotton—the South's staple crop and a linchpin of the regional economy—prompting a 70 percent slide in the commodity's price and triggering an economic earthquake in the southern United States. The collapse of cotton prices threatened the solvency of numerous small banks in the region. In response, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta stepped in to prevent teetering lenders from failing by lending them money at low interest rates.

The cotton trade was an intricate global business that started with tenant farmers and other growers across the Southeast and Texas and involved small local equipment suppliers and lenders; larger financiers in New Orleans, New York, and London; and textile and apparel mills in the United Kingdom. As late as the 1920s, cotton was America's largest export, and the U.S. South the primary supplier to the booming mills of Great Britain. So, when cotton prices plunged after a wartime commodities boom, it triggered a severe recession in the Southeast (see the chart).

For numerous banks in the region, most of them tiny by today's standards, cotton was the main source of business. Roberds and White write that rather than pushing the crop to market at money-losing prices, millions of bales piled up in warehouses. Fire sales of the huge inventories "would provoke widespread bank failures and the collapse of the credit chains on which cotton production depended," according to Roberds and White's Policy Hub article.

The moves by the Atlanta Fed to save the cotton banks generally worked. Yet not everyone was pleased. Most notably, the Fed Board of Governors in Washington, DC felt—with some justification, according to the requirements of the Federal Reserve Act—that the lending in its Atlanta regional bank was placing unnecessary pressure on the System's gold reserves.

The Fed Board of Governors chair (then called governor), William P.G. Harding, considered the cotton crisis a regional problem endangering relatively few banks and borrowers so felt the Fed should not intervene. To make his point, Harding wrote Wellborn a letter threatening to shut down the Atlanta Reserve Bank's emergency lending.

Wellborn, a former commercial banker from Anniston, Alabama, felt otherwise and acted accordingly. "Basically, Wellborn's thinking was that ultimately, after World War I, everyone will want new clothes, and we'll sell the cotton," Roberds said. "But let's not dump it all on the market at the same time."

Interestingly, Harding and Wellborn were friends as both had been bankers in Alabama. In fact, Harding was largely responsible for Wellborn's appointment as the Atlanta Fed's first leader, according to A History of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Sixth District by historian Franklin M. Garrett.

In a sense, the Atlanta Fed and Wellborn would be vindicated, though this vindication would not come for another decade. The bank's emergency actions anticipated debates that led to the 1932 passage of Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, giving the Fed "lender of last resort" powers that were standard for many countries' central banks at the time. Section 13(3) codified much of what Wellborn had essentially done on his own and furnished the legal authority for the Fed's emergency measures during the Great Recession of 2007–09 and the pandemic recession today.

Research reveals perils of a monolithic economy

The century-old dispute over the Atlanta Fed's lending even highlighted fundamental questions about the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 that established the central bank. In particular, some economic thinkers of the day believed that the act should designate only four or five districts, so that a smaller region with a single dominant industry—like the South with King Cotton—would not stand alone as a Fed district. Of course, the act created the 12 districts that make up today's Federal Reserve System.

The Roberds-White paper illuminates more than central banking history. The work also reminds readers that 55 years after the Civil War, the Southeast remained an agrarian economy. To take one state as an example, agriculture accounted for roughly half of Georgia's employment in the early 1920s, according to census data, compared to less than 1 percent today.

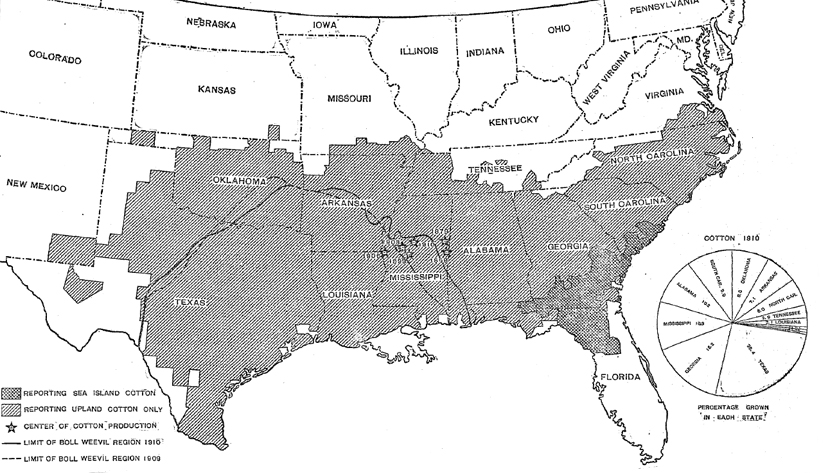

Because that farm economy was dominated by cotton, the region's prosperity was anchored to the fortunes of that staple (see the map). Cotton prices dipped sharply at the start of World War I then rebounded and even doubled within a few years.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Cotton Production and Statistics of Cottonseed Products: 1910

Buoyed by those high prices and expectations of a postwar recovery of export demand, U.S. growers in 1920 increased production by nearly 20 percent from the previous year, Roberds and White wrote.

Such optimism was a big mistake. Domestic and export demand stagnated amid a second postwar recession, and by the fall of 1920, Roberds and White wrote, "the mismatch between anticipated and realized demand became apparent to the markets, and by early 1921, cotton prices were running at less than 12 cents a pound, a 70 percent falloff from levels of the previous summer."

Breaking new ground

The dispute between the Atlanta Fed and the Board of Governors—and other aspects of regional Reserve Bank history—will receive further analysis in a forthcoming paper by White and Ellis Tallman, research director at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. Roberds said these studies of early regional Reserve Bank activity break fresh ground, as most research of Fed history has focused on national events in part because documentation is more accessible.

The research holds lessons for today's policymakers as well as historians. Historical lessons are perpetually useful, as parallels between the past and present come around again and again, Roberds points out. The 1920 cotton crisis was an important milestone in central banking history as it helped to shape the evolution of the Fed as a lender of last resort.

Also, concerns surrounding the Fed's powers to safeguard financial stability and the economy arose again as the central bank took emergency measures to buy huge volumes of securities and extend loans to private entities during more recent crises. Thus, the century-old policy debate helped shape central banking in ways still felt today.