When Whitney Strifler describes her 29 years at the Atlanta Fed, her account lacks a milestone some colleagues highlight: Strifler's role in warning of the housing market's collapse on the eve of the Great Recession.

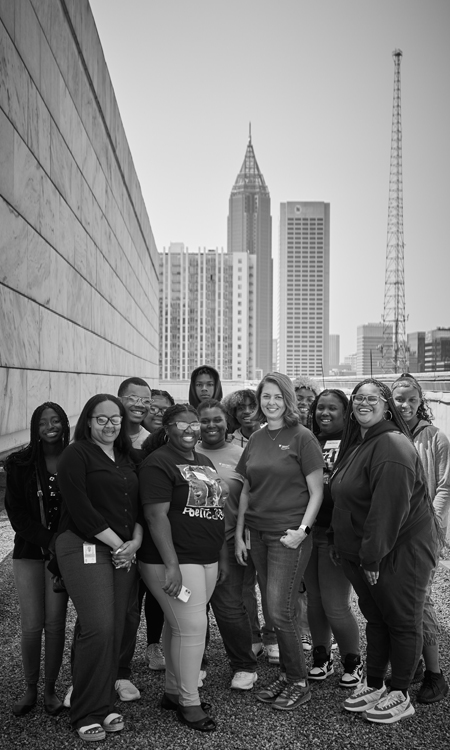

In addition to Whitney Strifler's work as an economics policy analysis

specialist, she started the Bank's Career Experience for teenagers who

attend Title 1 schools. Photo by Stephen Nowland.

In addition to Whitney Strifler's work as an economics policy analysis

specialist, she started the Bank's Career Experience for teenagers who

attend Title 1 schools. Photo by Stephen Nowland.

In late 2006, one of Strifler's jobs was to contact home builders to ask about past and present sales and expectations for the future. She reported that her contacts cited a steep downturn in residential construction with no recovery in sight. This information was an outlier among more measured housing reports across the country. Strifler held her ground.

"All the other [Federal Reserve] Banks were saying, 'We think we dodged the bullet with housing,'" said Melinda Pitts, Strifler's supervisor for the past decade and research center director of the Atlanta Fed's Center for Human Capital Studies. "Whitney said her contacts were saying it was going to be bad. And Pat [Barron] took that to the FOMC [Federal Open Market Committee]."

Barron, then the Atlanta Fed's chief operating officer, was filling in during a vacancy in the president's post. Barron presented to the FOMC a comprehensive description by Sixth District experts of a housing scenario that included grim reports from builders and spillover into related sectors. The Sixth District's report was the only one to dive deeply into housing.

According to a transcript of the December 12, 2006, meeting, Barron reported:

The decline in housing market activity is affecting housing-related sectors such as construction, real estate services, wood products and manufacturing, and carpet production, to which our District is more exposed than are other parts of the country. … Lending related to real estate has been a significant source of revenue and growth for District banks in recent years. Our banking contacts report that the pipeline of real estate lending has all but dried up.

The Great Recession began the next year. Residential construction plummeted nationwide, and through 2022, the annual rate of production did not rebound to the number of units built in 2007, according to a Census report. Approximately 3.8 million homes would be foreclosed on nationwide between 2007 and 2010, according to a 2016 analysis by the Chicago Fed.

Pitts tells this story in response to a question about whether she'd had a moment when she realized there is something special about Strifler. The anecdote illustrates Strifler's central character traits that impress Pitts.

"She's detail-oriented and has a great ability to synthesize large amounts of information and pull out what's important," Pitts said. "She's terribly good at identifying what's important."

After working as an intern in 1992, Strifler joined the Atlanta Fed full time in 1994. She had majored in computer science before shifting to business at the school now named Valdosta State University. Women were rare in her field then, accounting for about a quarter of the US workforce in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math), according to a report by the US Department of Labor. Strifler emphasizes she is not an economist.

"I'm not a math whiz," Strifler said. "I was good at math, but never thought I was amazing. I do like numbers."

Strifler created a niche as a researcher of economic conditions. In her 29 years with the Atlanta Fed, she has monitored sectors as diverse as oil, gas, and retail. She managed paper surveys that were mailed to partners before surveys were online, when she worked as a regional analyst in an era before the Bank established the Regional Economic Information Network (REIN). She worked several years as an analyst with Atlanta Fed executive vice president and chief economic adviser Dave Altig on macroeconomic and policy matters. She moved to Community and Economic Development and worked with Stuart Andreason, director of the Center for Workforce and Economic Opportunity.

In her early days at the Bank, Strifler met a fellow intern she would marry. Married life didn't work out as she'd expected.

"I thought I was going to be a teacher and a housewife," Strifler said. "When I had my first child, the economics of it were that I couldn't be a stay-at-home mom." The family was among the 52 percent of US households in the mid-1990s where both spouses were in the labor force, according to a report by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The marriage didn't survive. Strifler found herself a single mom rearing four children, two of them twin boys. One child was diagnosed with dyslexia, a learning disability that involves written words. The Bank provided her flexibility that enabled her to continue working full time while allowing her time to be the mother she wanted to be. She served in her children's schools as room mother and story-time reader and watched over them on field trips. Strifler has remarried.

"I probably didn't progress in my career as much as other women, but I made this choice and understood there was a cost to it," Strifler said. "In my mind, I had my kids for only that amount of time and, hey, they were my priority. I wouldn't change the decision I made. I enjoyed being a mom and my work life, and what benefits my family and me as a professional working woman. I think I've grown four really nice people, three mom's boys and my daughter—we're too much alike."

"She's detail-oriented and has a great ability to synthesize large amounts of information and pull out what's important. She's terribly good at identifying what's important."

— Melinda Pitts,

research center

director, Atlanta Fed Center for Human Capital Studies

John Robertson has known Strifler throughout his 26-year career at the Bank, sometimes as a collaborator and others as her manager. Robertson now serves the Bank as a senior policy adviser and economist on the macroeconomics and monetary policy team in the Research Division.

Like Pitts, Robertson cited Strifler's reliability, commitment to the Bank's initiatives, and ability to see the big picture. He said her love for her family is very important to her, and she has a knack for incorporating her lived experiences with the theoretical work of economists. For example, he said, when Strifler takes a family vacation to Walt Disney World, she comes back with an anecdotal report about attendance.

"Economists sometimes are trained to think in abstract ways that are disconnected from reality. Whitney always is good about bringing things back to the real world," Robertson said. "It's not just calculating some statistics. She recognizes this is about real people's lives and situations."

Robertson's portrayal matches Strifler's sense of self. She talks about how her research into her son's dyslexia led her down a path that culminated in starting a summer youth program she ran for a second time this summer. The Bank's two-week Career Experience helps teenagers who attend a Title 1 school explore career opportunities and pathways.

It started with Strifler reading up on her son's condition. She learned that boys with undiagnosed dyslexia tend to drop out of high school. Another report showed half the prisoners in Texas prisons have dyslexia. This led to her interest in helping youngsters with disorders or who come from disadvantaged homes, a situation that can be associated with a lack of economic mobility. She shared results of her research in stories for Economy Matters and fostered the formation of Career Experience, which convened again in June.

Strifler coordinated two weeks of programs at which students got to meet and interact with a total of more than 70 Bank employees and educators from Georgia State University and Atlanta Technical College. Students discussed everything from professional etiquette to résumé writing to crafting a LinkedIn profile and managing a bank account. They took most meals in the cafeteria instead of a conference room, part of a subtle message to show the students a diverse workplace where they could see themselves working.

A thread that runs through Strifler's work at the Bank: one of adding value to the things she touches.

"It doesn't have to have a huge impact," Strifler said. "If it helps the Bank president make better decisions, that's great. But if I'm being impactful in helping a young person see possibilities or give them encouragement, that's important, too. Whether it's big or small, I want to do work that matters."