Louisiana's oil and gas refineries are sprawling industrial complexes designed to never shut down. Many, like this one, are located along the Mississippi River. Photo courtesy of ExxonMobil

Louisiana's oil and gas refineries are sprawling industrial complexes designed to never shut down. Many, like this one, are located along the Mississippi River. Photo courtesy of ExxonMobil It's a strange business, energy.

Almost no one can live without it, so there's always a market. But the key to prosperity for those who produce and sell oil and natural gas is to fetch a reasonably high price for the commodity—just not too high, lest that unleash a flood of supply and push prices back down again.

Achieving the Goldilocks equilibrium—a price not too high and not too low—has proven elusive. The British magazine The Economist has tracked global commodity prices since the mid-1800s and declared in late April that in its oil price data for the past 160 years, "the most striking feature is the absence of any discernible pattern or trend."

Natural gas prices have been bumping along rock bottom for the past few years, thanks to a production boom fueled by fracturing technology, or fracking, and horizontal drilling. More recently, a global oil glut pushed down crude prices. Throw in a worldwide pandemic that squashed demand for petroleum products, and conditions went from difficult to dire.

These events also apply to a venerable engine of Louisiana's economy. Through dizzying swings in fortunes, energy has remained a cornerstone of the state's economy for more than a century. From 2008 through 2017, the industry accounted for 16 percent of Louisiana's economic output annually, on average, according to the most recent data available from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. That's a sizable share, yet it's half of what it was in the 1980s (see chart 1). When the combined output of Louisiana's energy sector is adjusted for inflation, it exceeded $80 billion a year in the early 1980s, fell to about $70 billion by 2005, and slid to $28 billion in 2017.

Industry employment has fluctuated, too. It topped 120,000 in Louisiana in the early 1980s and currently sits at about 75,000, with many of those jobs servicing clients outside the state (see chart 2). Although official industry-specific employment data aren't yet available, it appears the coronavirus shutdown damaged Louisiana's energy workforce. The Louisiana Oil and Gas Association, a trade group, reported that its members laid off 23 percent of employees, according to a survey released May 4. Fifty-one percent of the survey respondents said bankruptcy "is likely."

The owner of Louisiana's largest refinery cut 70 percent of its contractors and 16 percent of its employees nationwide, according to the firm's earnings conference call in early May. Another Louisiana refinery pared its contract workforce by 1,800 people in March, according to multiple news reports. Refineries typically employ roughly equal numbers of contractors and corporate employees.

Oil and gas jobs are vital to Louisiana for reasons beyond their numbers. They also pay above state median wages and pack a powerful "multiplier." On average, each job in oil and gas extraction, refining, and pipeline transportation in Louisiana generates another 3.4 jobs in other industries, according to an April 2018 study prepared for an energy advocacy group.

Gross domestic product and employment figures in this article are for the core sectors of the industry. The data likely understate the true impact of the industry because the statistics don't count activities such as the construction activity and legal and accounting work done on behalf of energy companies.

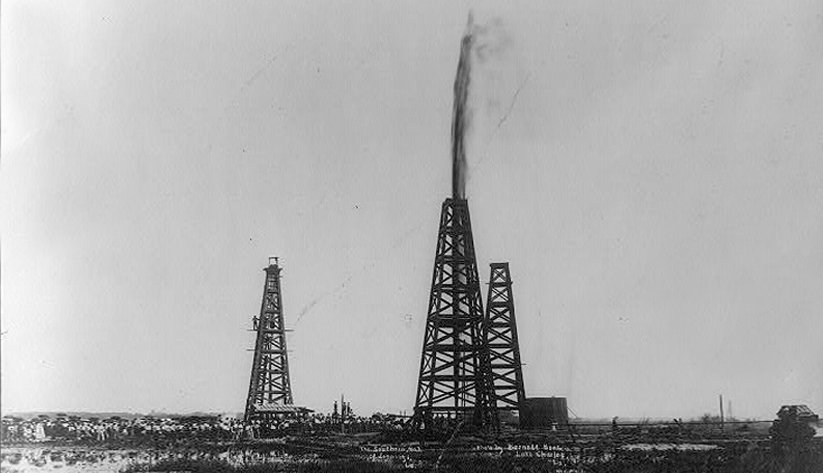

Louisiana onshore and near-shore oil production steadily increased until the 1970s. These are derricks in northwest Louisiana around 1919–20. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress photographic archives

Even before the coronavirus pandemic, mining and logging employment in Louisiana, which means mainly oil and gas extraction, had shrunk by nearly 20,000 jobs since late 2014, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The bulk of those job reductions were in south Louisiana.

The slide in employment followed the global oil surplus that rendered much Louisiana oil and gas unprofitable to extract. Unlike some other oil industry states like Texas, Louisiana's extraction employment did not rebound alongside oil prices around 2016. In part, that rebound didn't occur because some of the production platforms off the coast of Louisiana shut down a few years ago and never restarted because for certain firms the economics didn't make sense, said David Dismukes, executive director and professor at the Center for Energy Studies at Louisiana State University. In May, 53 operators were producing oil and gas in the gulf, down from 91 in 2014, according to the U.S. Interior Department's Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement.

Business has gone downstream

As Louisiana's energy industry has shrunk, its composition has shifted. Refining and processing—the "downstream" end of the business—has supplanted "upstream" exploration and production as the industry's centerpiece in the state, at least in terms of the share of state GDP.

In part, that's because companies have already gotten much of the state's most affordably extracted oil and gas. The state's crude oil production has steadily declined to roughly a tenth of its high point of more than 500 million barrels a year in the early 1970s, according to the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources (DNR) (see chart 3).

The same general pattern of steady decline held for natural gas until the advent of shale fracking and horizontal drilling boosted output over the past decade. Even as natural gas prices have been depressed, better technology is lowering the price at which producers can make money. Louisiana gas production by 2019 was back up to early 1980s levels, though still well below the early 1970s peak, DNR data show. Most Louisiana oil and gas production has migrated from southern Louisiana to the northwest part of the state.

As Louisiana oil and gas extraction outside the deepwater gulf has ebbed, refining has grown. In a significant reversal, refining and pipeline transportation generated more economic output than oil and gas extraction and support activities for eight straight years through 2017. Extraction and support activities constituted a far bigger economic force in the state until the 21st century (see chart 4).

This evolution happened even as the number of refineries in Louisiana dwindled to 17 from double that number in the 1980s. But the amount of crude oil and natural gas that facilities can process soared as refiners invested heavily to modernize plants, said Dismukes. Numerous billion-dollar-plus refinery projects announced in recent years face uncertain fates, however, given the severe economic downturn, along with trade tensions and a global economy that was already slowing, according to Beige Book reports.

The infrastructure already in place is formidable. Three of the nation's seven largest oil refineries, based on capacity, are in Louisiana. Roughly half of all U.S. refining capacity is in Louisiana and Texas, according to statistics from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). These Gulf Coast refineries are also extremely efficient, in part because many are tied to adjacent petrochemical plants to form complexes that wring every ounce of use out of oil and natural gas, Dismukes said.

But depressed fuel prices can wreak havoc on refiners. Facing paltry demand for gasoline, diesel, jet fuel and other refined products, Louisiana refineries in May were operating at about 70 percent capacity, a historically low level, according to the EIA.

Production cuts at refineries do not represent a worst-case scenario for Louisiana, however. For refiners and the Louisiana energy economy broadly, a truly dire circumstance would see refineries shutting down entirely, even if temporarily, according to Dismukes. "That is a scary scenario and is the one that gives me the most concern because it's never happened," he said.

Refineries are vast networks of machinery meant to run constantly. Louisiana's biggest, at Garyville, sprawls over 3,500 acres, three times the size of Louisiana State University's campus in Baton Rouge. And many refineries and petrochemical plants inhabit a sort of interconnected industrial ecosystem, where a bottleneck in one spot can trigger problems that cascade elsewhere. Restarting refinery complexes, Dismukes said, would be costly, painstaking, and likely require significant efforts to meet regulatory compliance.

Oil and gas production appears likely to keep declining

Setting aside cyclical troubles, oil and gas production will probably continue declining in Louisiana, said Dismukes, even as the business of refining and transporting hydrocarbons powers ahead.

Charles Goodson sees these trends play out daily. Chief executive of PetroQuest Energy, a Lafayette-based exploration and production firm focused on natural gas, Goodson believes south Louisiana's hydrocarbon production is in its twilight. The upstream business there, Goodson said, will never again approach the heady days of the 1970s and '80s.

"Your producing bases in America will be focused on shale basins, unless new technology that is unforeseen today is developed," said Goodson, a member of the Atlanta Fed's Energy Advisory Council. He noted that few in the industry foresaw the massive production that horizontal drilling and fracking would unleash.

In Louisiana, the main shale lies underneath the northern part of the state. As for proved oil reserves, Louisiana claims less than 1 percent of the U.S. total, far less than Texas, North Dakota, and a half dozen other states, according to the EIA. The Gulf of Mexico, on the other hand, still harbors considerable oil reserves.

In contrast to the boom-and-bust production game, the downstream business is comparatively stable. Unlike production equipment, refineries, petrochemical factories, pipelines, and oil and gas seaports constitute an expansive infrastructure that can't easily move or shut down. Global companies situated the facilities in south Louisiana for reasons that won't disappear: proximity to production, Gulf ports, easy navigation on the Mississippi River, and access to 90,000 miles of pipelines. Despite concerns about temporarily idling refineries, Dismukes figures the highly productive Gulf Coast facilities would be the nation's last to permanently close.

Observers tend to believe the Pelican State will maintain a substantial energy industry in the long term. Chances are it will increasingly be a "downstream business," particularly in the traditional oil patch of south Louisiana. Nevertheless, the state's longtime economic bedrock faces questions. "What we don't know," Dismukes said, "is what the long-term, structural changes in energy demand are going to be."

Louisianans await the answer to that question with great interest.