Birmingham Regional Executive Anoop Mishra talks with Alabama farmer Larkin Martin, a member of the Atlanta Fed agriculture advisory council.

Birmingham Regional Executive Anoop Mishra talks with Alabama farmer Larkin Martin, a member of the Atlanta Fed agriculture advisory council.Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic emphasizes that few Americans experience the average economy that national statistics describe. Even in normal times, economic prosperity and opportunity vary across and within states and metropolitan areas. A recession brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated those disparities.

The persistence of uneven economic conditions is one reason grassroots economic intelligence gathering is critical for the Atlanta Fed to fully understand the diverse economic experiences across the Southeast. Another key reason: official statistics are inherently backward looking. By talking to business decision makers and community leaders, the Atlanta Fed’s Regional Economic Information Network (REIN) staff compose a real-time view of these conditions to provide clues about the road ahead.

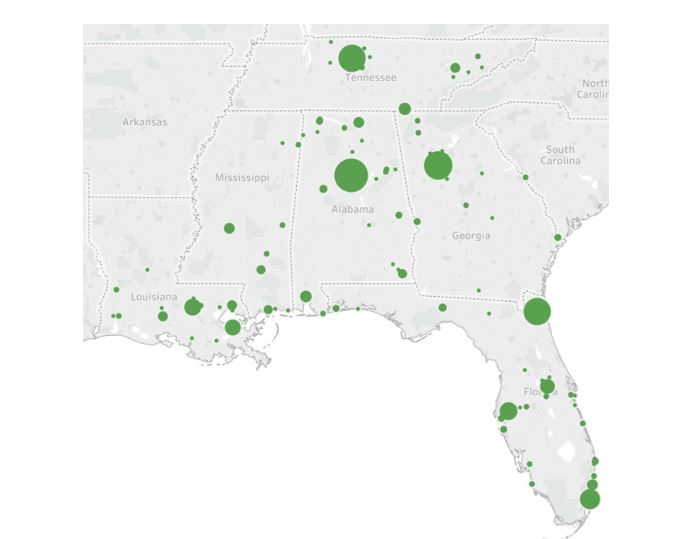

At the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, REIN staff in Atlanta and the Bank’s branch cities (Birmingham, Jacksonville, Miami, Nashville, and New Orleans) intensified efforts to gather intelligence on the pandemic’s sweeping economic effects—from production cuts at oil refineries to increased demands on nonprofit organizations. Since mid-March, the REIN team has conducted mostly one-on-one meetings with over 600 executives and other leaders across the Southeast, sharing those insights with Bostic and Atlanta Fed researchers as they formulate monetary policy (see the map). The REIN team has relied heavily on relationships cultivated over more than a decade to glean candid assessments from businesses of all industries and sizes, ranging from one-person startups to multibillion-dollar corporations.

All Over the Map: Concentrations of REIN Interviews from Mid-March to Early June

Widespread stay-at-home orders starting in March halted huge swaths of economic activity. Almost immediately, 22 million jobs disappeared, and April brought the biggest one-month plunge in consumer spending on record. A few weeks on, REIN reports that coincide with early stages of business reopenings in many states from May and early June reveal glimmers of recovery, and even robust rebounds in some industries. However, those hopeful signals are punctuated with question marks.

Certain types of tourism, retail signal a fragile rebound

As May progressed, contacts reported notable improvement in industries dependent on consumer spending, including beach and mountain destinations that tourists can drive to; discount retail, apparel, sporting goods; and home decor and improvement. The chief executive of a midsized discount retailer noted sales were 20 percent above normal during a recent six-week span. Vacation houses and campgrounds are generally booked for the summer. Nationally, consumer spending rebounded in May off the low April levels, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce, reinforcing the REIN team’s anecdotal evidence. In addition, some manufacturers with multiyear sales cycles, such as producers of complex industrial infrastructure, say they expect little long-term harm from the pandemic.

During normal times, a pickup in business might spur hiring and investment. Times are anything but normal, though. In the Southeast’s large tourism industry, even as activity accelerated in certain places, major attractions remain closed while others have only partially reopened, and cruise lines sailing from Florida and New Orleans won’t resume operations until August or later.

Merely reopening businesses is complex. Safety and health guidelines and rules differ across jurisdictions, complicating plans, especially for businesses with large territories.

Of perhaps more concern, many contacts worry that recent consumption is built on a shaky foundation. They cite two main reasons. First, spending may be fueled by temporary supports that will soon end, including direct economic impact payments from the federal government, expanded unemployment insurance benefits, and forbearance programs from utilities and mortgage lenders. Many financial relief programs are slated to end this summer, and if supports phase out soon, numerous district firms fear that many consumers’ financial situations, and their spending patterns, will deteriorate.

Second, the labor market might not fully recover for some time. A shaky labor market saps incomes and confidence and depresses consumption. About 75 percent of unemployed workers reported their layoff is temporary in the most recent household survey the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) uses to produce its monthly employment reports.

Unfortunately, potentially durable, or structural, shifts in the economy might undermine the notion that most laid-off workers will simply be rehired into their old jobs, according to REIN findings and other research. In recent Atlanta Fed conversations, for example, most employers said rehiring will hinge on a rebound in their business activity. If recent upticks in demand for goods and services prove temporary, hopes for rehiring would prove fleeting. Even if businesses flourish, many firms reported they might experiment with a smaller workforce or replace some positions with lower-level jobs. Research by economists who work with the Atlanta Fed on business surveys affirms that notion, suggesting that—as of late June— anywhere from 32 percent to 42 percent of jobs lost during the pandemic recession might not return.

Atlanta Fed research director Dave Altig. Photo by David Fine

To be sure, hiring has not stopped entirely. Nationwide employment increased in May, and recent Atlanta Fed surveys find that three jobs were created for every 10 lost during the pandemic. However, new jobs are probably in different economic sectors from the eliminated positions, said Dave Altig, Atlanta Fed research director. Such a shift in job composition would complicate a return to work for many, as it’s tough to quickly learn new skills and change industries. Moreover, new staffing models might include permanent shifts toward online operations, leading to lower staffing demands.

More remote work a mixed bag

Atlanta Fed surveys find as the pandemic recedes, companies could triple the amount of time employees work at home.

While welcome news to some workers, a rise in remote work could rattle industries such as commercial real estate, office supply manufacturing and selling, and transportation, Altig said. Already, Atlanta Fed contacts noted that questions about commercial real estate usage could shrink the staffing needs for areas such as facilities and event management.

These unknowns feed what Fed chair Jerome Powell calls “extraordinary uncertainty” about the direction of the macroeconomy. A maxim of modern-day economics, Altig pointed out, holds that uncertainty is “the bane of growth.” And he said this fog of uncertainty is unlikely to clear soon, in part because so much remains unknown about the state of public health.

“These are huge questions related to structural adjustments in the economy that we just don’t think are going away,” Altig said in a recent webinar. “It will take some time to sort through this.”

Southeast businesses grapple with uncertainty

Businesses appear to grasp that message. Most organizations REIN contacted expect to be managing aspects of the pandemic for the rest of 2020 or longer. Reports from firms vary but generally suggest demand for goods and services is not expected to reach precrisis levels until late 2021 or 2022. Of course, much depends on efforts to contain the coronavirus. While little appetite exists for closing economies again, several Atlanta Fed directors and contacts expressed serious concern about a resurgence of COVID-19 cases as businesses reopen.

For now, the course of the virus is perhaps the fundamental uncertainty confronting business decision makers, workers, and the macroeconomy. “This,” Bostic has repeatedly stated, “is first and foremost a public health crisis.”

As the pandemic and its consequences continue to reverberate throughout the economy, the REIN team will continue to seek intelligence on the resumption of economic activity across the Southeast.