It is rare that the course of a multi-trillion-dollar economy may depend on something as mundane as people being vaccinated. But then little is routine in an economy upended by a global pandemic.

The success of broad inoculation programs will largely determine the timing and vitality of an economic rebound after a steep downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and accompanying public health measures, according to the latest feedback from business decision makers across the Southeast gathered by the Regional Economic Information Network (REIN) staff at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

REIN staff in recent months intensified efforts to gather information to better understand the pandemic’s effects on communities and businesses, from one-person shops to multibillion-dollar international corporations. Atlanta Fed researchers and policymakers are increasingly relying on these real-time anecdotal reports to help understand the macroeconomy and add texture to the published data.

The sooner large portions of the population receive COVID shots, the sooner the pandemic will recede and the sooner people are likely to resume traveling and spending in restaurants, retail stores, movie theaters, and other settings where crowds typically gather, according to Atlanta Fed contacts.

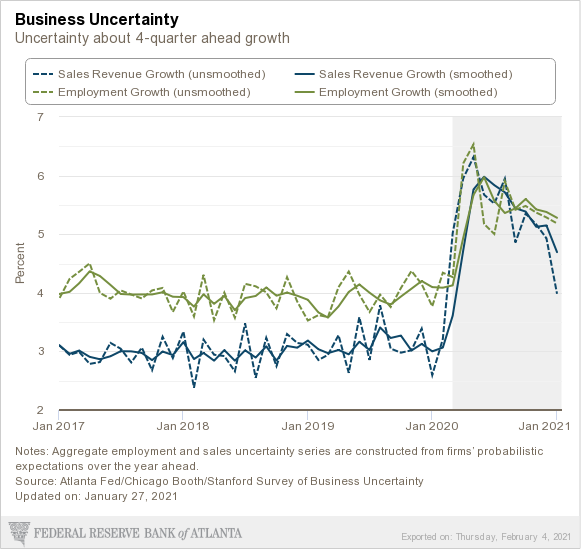

Most business leaders across the Atlanta Fed’s six-state district (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and parts of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee) expect consumer confidence and thus commerce to rejuvenate over the second half of 2021 and into 2022—that is, if officials can remedy early snags in vaccination programs and thus achieve extensive inoculation by mid-2021. While REIN staff did not detect a great deal of optimism across the region, the general mood of businesspeople brightened recently (see the chart). The view shifted from last year’s question—is a vaccine coming at all?—to wondering whether it would reach enough people by mid- to late 2021 to trigger an economic resurgence.

“The longer we have people that have to bridge the gap from downturn to a rebound, and large numbers getting relief as opposed to looking forward, the more risk we have that this recovery will not be as robust as it could be,” said Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic, a voting member of the policy making Federal Open Market Committee in 2021. “This is where the progression of the virus becomes very important because in many regards, that will determine how robustly the economy can recover.”

Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic. Photo by David Fine

The southeastern economy broadly mirrors the nation’s, as it grinds through what Bostic calls a “less-than recovery.” His comment refers to the sign (<) mathematicians use, and he means it to indicate the unevenness of the recovery among households and businesses. For example, certain workers, mainly professionals who can easily work from home, are on an upward trajectory while service industry employees and others who cannot work remotely generally struggle, as represented by the downward-sloping line. A similar divergence is playing out among industries: those reliant on face-to-face transactions and travel are struggling, unlike online retailers and sellers of home products, for example.

One foot on the gas, one on the brake

Planning big-ticket strategic investments doesn’t mesh well with rampant uncertainty. One business leader told REIN staff that the current environment is like “having one foot on the gas pedal and one on the brake.” One logistics firm has even added numerous virus-related metrics in judging the merits of specific capital expenditures, including thresholds related to increases in conducting face-to-face business with customers and the portion of the general population vaccinated.

Some smaller firms expressed a reluctance to spend on inventory lest a slow rebound leave them stuck with products they can’t sell.

On the other hand, again reflecting the less-than dynamic, a number of firms report taking advantage of opportunities to expand by acquiring financially troubled rivals.

Shortage of containers tangling supply chains

As investment decisions remain tricky, the circulatory system of the goods economy is also still sluggish, putting some upward pressure on certain costs. Many contacts expect these supply chain disruptions to last through the second quarter of 2021. One contact’s company waited six months rather than the customary two weeks to receive power supplies it needs for its products. In response, the firm shifted from overseas to costlier domestic suppliers.

Multiple contacts cited headaches caused by a scarcity of shipping containers, the large, cargo-laden boxes that are stacked on ships and then offloaded onto trains and trucks. As consumers have dramatically shifted from spending on services such as restaurants and movie theaters to purchasing record amounts of imported clothing, computers, furniture and other goods, the global supply of containers has been unable to keep pace.

One firm noted that a container shortage is choking its exports out of the port of Savannah, Georgia. Another importer told Atlanta Fed REIN staff that the dearth of containers in November and December had doubled the cost of securing them.

Other pandemic-related supply chain disruptions occurred as well. An importer of appliances said virus outbreaks at factories in Mexico had curtailed its inventory from that country by about 75 percent.

Complex forces roiling the labor market

Business contacts noted that a tangle of sometimes contradictory forces makes workforce planning unusually complicated. A return to in-person schooling and diminishing concerns about potential virus exposure at work figure to bring more people back into the labor force. A more robust vaccine rollout could help on both fronts.

Most businesses in touch with the Atlanta Fed indicate they plan to encourage or in some cases even pay employees to get vaccinated, rather than require them to be inoculated. For instance, a beverage firm is offering workers $200 to get both doses, while major retailer Dollar General announced plans to pay workers the equivalent of several hours’ wages after getting vaccinated. Other retailers including Aldi, Trader Joe’s, and Instacart have publicly shared similar programs.

As more and more people get shots, improved public health should translate into improved economic health. So hope—mainly in the form of medicine, hypodermic needles, and the effort to distribute the vaccine nationwide—abides even amid the uncertainty.