Before the introduction of containers in the late 1950s, ships typically

spent more time docked than at sea. Now, absent pandemic-induced delays,

container ships typically spend only one to four days at a time in port.

Here, thousands of containers sit at Savannah’s Garden City Terminal.

Photo courtesy of the Georgia Ports Authority

Before the introduction of containers in the late 1950s, ships typically

spent more time docked than at sea. Now, absent pandemic-induced delays,

container ships typically spend only one to four days at a time in port.

Here, thousands of containers sit at Savannah’s Garden City Terminal.

Photo courtesy of the Georgia Ports Authority

That elusive video game console your kid craves could be sitting on a landing strip at a small South Georgia airfield. Although the Statesboro Bulloch County Airport is not an international cargo hub, in late 2021 its second runway was stacked with shipping containers from the overflowing Port of Savannah.

So goes the great supply chain disruption of the 21st century.

Snarls in the supply chain—the global web of factories, trains, rail yards, trucks, warehouses, ships, seaports, and airports—are perhaps nowhere more apparent than at the nation's seaports. After all, ships transport more than 90 percent of cargo that enters or leaves the United States.

Since most consumer goods enter the United States in 20- or 40-foot-long metal boxes, those container ports became choke points. And even before COVID, those ports were plenty busy.

Ports worldwide handled about 50 percent more containers in 2019 than in 2010, while American ports handled 30 percent more containers, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

Since its inception in the late 1950s, containerized shipping greatly lowered the costs of transporting cargo. Cheap shipping in turn enabled the modern supply chain and just-in-time inventory management, meaning firms keep on hand only what they need at the moment and depend on suppliers to bring new material on demand. However, the global pandemic exposed weak links in the elongated, finely calibrated supply chains.

From colonial days to the mid-1800s when cotton sailing from Mobile, New Orleans, and Savannah was America’s leading export, seaports have played a large role in the economy of the Southeast.

Through the first half of the 1800s, the Port of New Orleans ranked second in the United States only to New York in traffic, writes Richard Campanella, a Tulane University geographer who has published extensively on the history of New Orleans. The first steamship to cross the Atlantic Ocean from the United States to Europe—the SS Savannah—sailed from, yes, Savannah in 1819.

The first steamship to sail from America to Europe, the SS Savannah, departed from Savannah and landed in Liverpool, England, in 1819. Image courtesy of the Digital Commonwealth Massachusetts Collections Online

Dredging and other port improvements that continue today have been under way since at least the early 1800s. The Port of Mobile, for example, sits atop a large but shallow bay. To remedy the problem of unloading cargo onto small boats at the bottom of the bay to bring it up to the port, the federal government in 1826 began financing work to dig a deeper channel through Mobile Bay.

Many miles to the south, the Port of Miami required similar deepening. In fact, the current facility opened in 1964 on an island built from dirt, or "spoil," from dredging and slicing a 900-foot-wide pass through the Miami Beach peninsula to afford access to the port.

Not all the region’s economic and maritime heritage is triumphal. Southern seaports were closely associated with slavery. Several coastal cities were centers of the trade in enslaved Africans who cultivated the region’s staple crops including cotton and sugar.

In positive ways, the influence of ports persists. To this day, New Orleans is home to more captains, mates, ship pilots, sailors, and marine oilers than any US metropolitan area, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

New Orleans was a major export hub for cargo including cotton and sugar. This photograph shows the city’s waterfront in the 1880s. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress photographic archives

The Crescent City is hardly the Southeast’s only maritime hub. More than a dozen ports in the region consistently rank among the nation’s top 25 in at least one key measure of cargo handled, either number of containers handled or tons of bulk or break-bulk cargo processed, according to data from the US Department of Transportation Maritime Administration and other sources. Those ports include Savannah, New Orleans, Jacksonville, Miami, Tampa, Mobile, the Port of South Louisiana, Brunswick, Baton Rouge, Gulfport, Pascagoula, Port Everglades (Fort Lauderdale), Lake Charles, Port of Plaquemines, and Palm Beach.

The Port of South Louisiana, mostly out of public view along the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, processes more than half of all US grain exports, much of it corn, soy, and wheat from the Midwest. Most seaports specialized early on and honed their focus over time, either through strategic decisions or natural evolution based on what is produced or consumed nearby.

The Port of Mobile houses a large terminal designed to export Alabama-mined coal. The Georgia Ports Authority in the 1990s convinced retailers including Home Depot and Walmart to make the Port of Savannah a major import hub. Other retailers followed suit, and the port is now busier than any US container facility outside the ports of Los Angeles, Long Beach, and New York-New Jersey. Meanwhile, the neighboring Port of Brunswick, in Georgia, handles about 600,000 cars and trucks a year, both outgoing, from assembly plants that began to proliferate in the Southeast in the 1990s, and incoming to dealerships.

Lumber has been an important cargo at the Port of Mobile for many years, as this 1900 photo of the port shows. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress photographic archives

At the Port of New Orleans, exports make up some 70 percent of the volume, notably petrochemical resins produced nearby and used in making plastics. Louisiana’s ports generally depend on exports in part because the state lacks the massive population to attract more imports. Louisiana leaders hope eventually to boost exports by attracting distribution centers to channel imports northward.

Miami is the busiest passenger port in the United States, in part because of proximity to the Caribbean. Several other Florida ports are also cruise hubs.

What happened? One of the critical triggers was a dramatic shift in how Americans spend money. Amid the coronavirus pandemic, the volume of US imports soared (see the chart). Homebound consumers splurged on products like computers and furniture, most of which come from overseas. In the 12 months through October 2021, in inflation-adjusted dollars, real personal consumption spending on goods was about $700 billion higher than in the 12 months through February 2020, just before the pandemic reached US shores. Over the same period, spending on services was down about $300 billion, according to the US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

This abrupt shift in purchasing habits combined with other forces to rattle the world's supply chain. Many retailers were unprepared for the sudden surge in demand and, as inventories became scarce, big firms scrambled to stock up to avert future shortages, straining the system. The change in consumption combined with shortages of maritime cargo containers and the chassis they sit atop, factory shutdowns as COVID cases surged, and a scarcity of semiconductors, truck drivers, and port workers, further straining supply chains.

Consequently, news outlets have brimmed with reports of cargo-laden ships idling outside harbors, especially at two southern California ports that handle nearly half the nation's consumer goods imports.

Seaports are sprawling industrial ecosystems.

Ships stacked skyscraper-high with containers and towering cranes are prominent cogs in the system. Less visible but equally vital are the tugboats and barges that transport goods within and beyond the seaports by way of rivers and canals.

Indeed, the humble barge industry has an image problem: a sufficiently low profile that "we don’t have much of a reputation at all," explained Douglas Downing, chief financial officer of New Orleans–based Canal Barge Company Inc. and a member of the Atlanta Fed’s trade and transportation advisory council.

Tugs hauling preassembled pieces of big construction projects along the Mississippi River. Photo courtesy of the Canal Barge Company Inc.

Although barges can’t take cargo everywhere it needs to go—it’s impossible to dock outside a big box retail store—the companies that push petroleum products, chemicals, grain, coal, and other cargo along rivers fill a crucial niche in the nation’s economic supply chain. First off, the US tugboat and barge industry directly employed 50,480 people and generated revenue of $15.9 billion in 2014, the most recent data available in a study by the accounting and consulting firm PwC and published on the US Department of Transportation Maritime Administration website. Louisiana is the hub of the industry, with some 16,000 workers in 2014, nearly triple the number in second-place Texas. In fact, four of the top 10 states in towboat and barge employment are in the Atlanta Fed’s Sixth District: Florida, Tennessee, and Mississippi along with Louisiana.

The PwC study says barges, measured by tonnage, accounted for 84 percent of all domestic waterborne commerce (defined as originating and terminating at US harbors and ports without going overseas).

Moving materials on barges is a cyclical business, Downing said. Change typically comes gradually to the tight-knit, collegial barge industry. After all, their main equipment—boats and barges—lasts from 30 to 60 years. Plus, barges are an efficient way to transport large loads, so there has traditionally been little impulse to radically rework things.

According to the American Waterways Operators, an industry trade group, a "tow" of 15 barges pushed by a single tugboat, a common configuration, moves as much cargo as can 215 rail cars or 1,000 tractor trailers, translating into less fuel consumption per ton of product shipped. Downing said that because of savings on fuel and other costs, his industry carries 16 percent of all freight moved by land, air, or water in the United States for about 2 percent of all spending on freight moved in the United States.

Stable as it is, changes are coming to the barge business—at least along the margins. To ease congestion at major container ports, barges could be used to haul some of the big metal containers. Downing said he’s unsure just how much container cargo will migrate from ships, trains, and trucks to barges, in part because barges are slow. (Barges go about three miles per hour upriver and 10 mph with the current.) That speed is not ideal for shippers looking to deliver products like TVs to impatient consumers, Downing said. "So it depends on what the cargo is," he said.

More fundamentally, the barge business is evolving on three other fronts. One, barge lines are gradually adopting more fuel-efficient and clean-burning engines, including diesel-electric hybrids. Two, firms are deploying technology to help pilots maneuver quarter-mile-long tows around bends and between bridge supports. A big problem is that the boats and barges inevitably slide sideways as the pilot turns, Downing explained. New navigational technology analyzes data on factors including speed and direction and river currents to tell the pilot exactly where their vessel will be in three minutes or five minutes, depending on how they position the boat’s rudders.

Finally, a couple of longtime staples of the barge business are diminishing. As the nation’s energy mix changes, demand is dwindling for coal and equipment for oil and gas drilling rigs. However, the same boats and barges that service offshore rigs and power plants could soon be ferrying gear to offshore wind power complexes, Downing said.

The Southeast has plenty of ports. Many of them are setting cargo records amid the wave of goods Americans are buying. Southeastern port operators are keeping an eye out for opportunities. Some regional ports are marketing themselves to frustrated shippers as alternatives to snarled ports. And in fact, shippers are diverting some cargo from congested seaports. Over the longer term, more fundamental shifts in global supply chains, such as moving production closer to consumers through "onshoring" or "nearshoring," could also generate business for southeastern ports.

With a notable exception, though, Sixth District ports have remained largely free of congestion, mainly because most are not major importers of goods shipped in containers.

The Port of Savannah, however, does handle many containers. It is by far the busiest container port in the region and the fourth busiest in the country. Savannah's port handled more than 5 million twenty-foot-equivalent-unit containers (TEUs, the standard measure of containers) in 2021, four times as many as the Jacksonville Port Authority, the next-busiest container port in the Southeast. Other harbors that primarily handle exports or traffic mostly bulk cargo—grain, coal, or oil, for instance—have not seen a similar explosion in container numbers and have not been overwhelmed.

A peak season that won't end

The growth in container volume at the Savannah port has been a mixed blessing. In its fiscal year ending in June 2021, Savannah handled 20 percent more containers than in the previous year, a volume that basically overwhelmed the port. The harbor had averaged a brisk 6.5 percent annual increase in containers processed for the past 15 years.

Despite its steady growth, the Port of Savannah entered the pandemic with a comfortable cushion of 20 percent spare capacity, said Griff Lynch, executive director of the Georgia Ports Authority and a member of the Atlanta Fed's trade and transportation advisory council. However, rather than holding for three or four years, "we just chewed up all capacity in one year, unexpectedly," Lynch said in an interview. Like retailers, port officials are accustomed to peak seasons around holidays. "We've had a nonstop peak season since September" 2020, Lynch said. "That's unprecedented."

Griff Lynch, executive director of the Georgia Ports Authority. Photo courtesy of the Georgia Ports Authority

As a result, containers that typically sat in the port four or five days after being taken off a ship stayed "on terminal" an average of 12 days during the Savannah port's most congested time in August and September 2021. Meanwhile, two dozen or more ships were lined up waiting to enter the port.

Port officials have taken numerous steps to ease operations. In the short run, in November, officials arranged to move thousands of containers off site: to the airstrip in Statesboro, 55 miles inland; to a rail yard five miles from the port; and to another idled rail yard in Atlanta, 250 miles away. In a project underway before the pandemic, the Georgia Ports Authority in November opened a new set of railroad tracks at the Savannah port.

Further expansion is coming. During the course of several months, the port aims to add acreage and infrastructure to handle an additional 1.2 million containers a year. The authority is also building a berth capable of hosting the largest container ships now cruising the oceans.

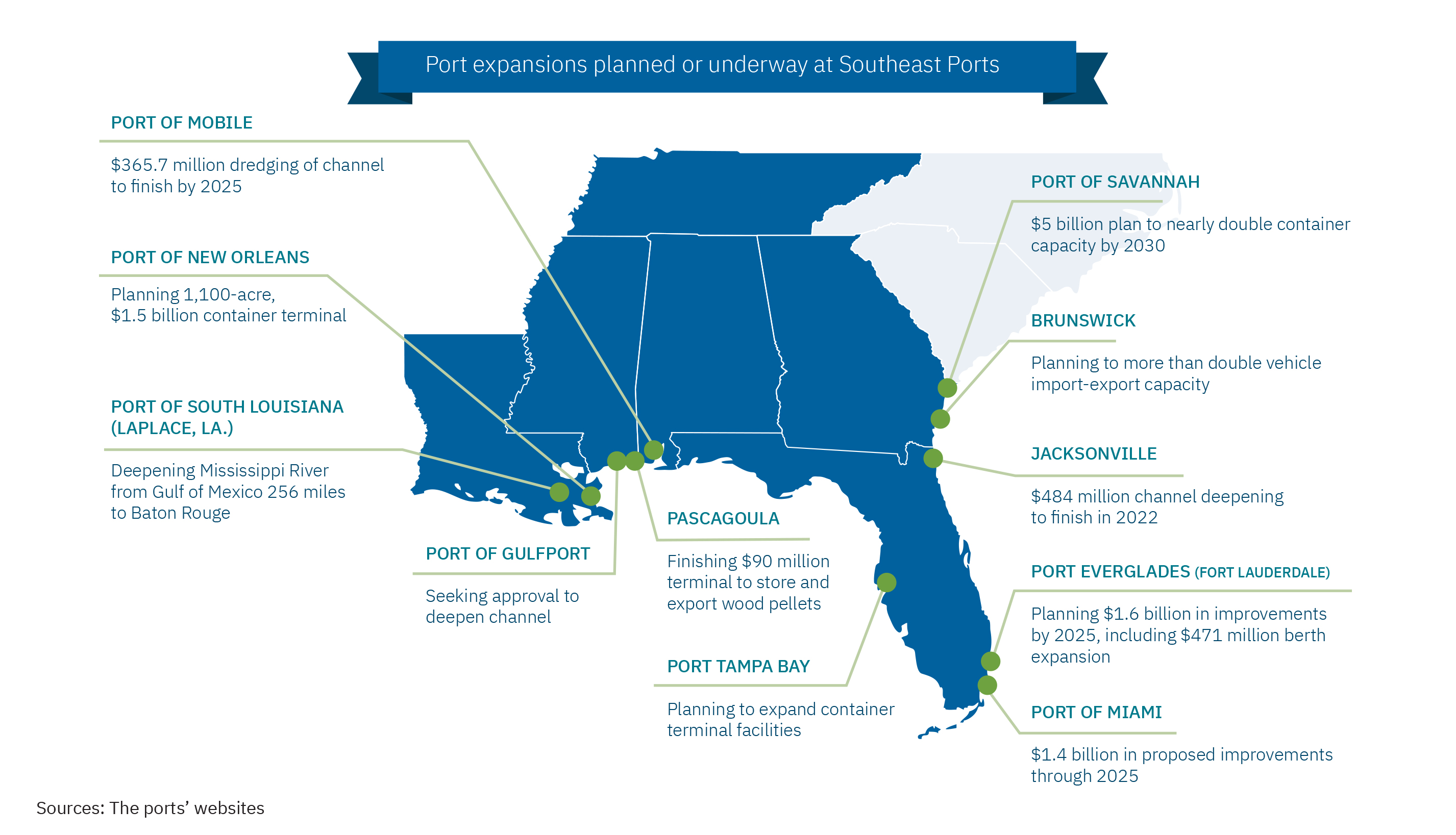

In the long run, Savannah—like most ports—has ambitious expansion plans, totaling nearly $5 billion. Whereas southeastern ports once spent millions to stamp out disease-carrying mosquitos and rodents, their more recent investments involve a race to grow and add cranes and other equipment geared toward servicing increasingly mammoth cargo ships (see the infographic).

As the Port of Savannah, like other ports, continues to try to resolve supply disruptions, signs of progress are emerging. In late November, containers were sitting at the port for 60 percent less time than in September. And the number of ships waiting to get in was down 40 percent, according to port officials. More broadly, global average prices for containers, while still much higher than a year ago, fell or stayed flat for eight consecutive weeks through November 18 before ticking up slightly in early December, according to Drewry, a shipping research and consulting firm.

The Port of Savannah handled more than 5 million containers this year, making it by far the Southeast's busiest container port and the nation's fourth busiest. Photo courtesy the Georgia Ports Authority

Still, it is unclear when global supply chains will return to normal. According to the December 1 Beige Book report on economic conditions, many of the Atlanta Fed's transportation industry contacts do not anticipate supply bottlenecks clearing until late 2022 or 2023. During October and early November 2021, air cargo carriers told Atlanta Fed officials they were seeing higher demand as the cost of container shipping exceeded air freight rates in some cases, which is highly unusual.

Even uncongested ports see effects of supply chain snags

To be sure, even the uncongested harbors in the Southeast have not entirely avoided getting ensnared, even indirectly, in pandemic-induced supply chain tangles.

Take New Orleans, for example. Port NOLA mainly handles exports, so it hasn't borne the brunt of the surge in imports. But it has fewer empty containers on hand because more full boxes are flowing to ports that, like Savannah, are seeing a crush of imports. And because New Orleans port operators need the empty containers to refill with materials for export, the paucity creates headaches.

At the same time, some cargo owners are choosing to transport products outside of scarce, and thus expensive, containers. From January through October 2021, the Port of New Orleans handled 40 percent more break-bulk tonnage—such as plywood, rubber, steel, or large machinery—than it did in the same period of 2020. (Break-bulk cargo is generally not shipped in containers.)

The Port of New Orleans is seeing increases in volumes of break-bulk cargo hauled on ships like these. Photo courtesy of the Port of New Orleans

Brandy Christian, president and chief executive officer of the Port of New Orleans. Photo courtesy of the Port of New Orleans

Amid the shortage of available containers, even some coffee bean importers, which began using containers in the 1970s, are considering reverting to break-bulk shipping, said Brandy Christian, president and chief executive officer of the Port of New Orleans and a member of the Atlanta Fed trade and transportation advisory council. Coffee has long been a staple import for New Orleans, given its proximity to Central and South America.

Florida ports "ready to offer a supply chain alternative"

Although ports tend to specialize in certain cargoes, they do compete. In recent months, several ports in the Southeast have promoted themselves as alternatives to congested gateways such as Savannah, Charleston, Los Angeles, and Long Beach.

In late October, the Jacksonville Port Authority reported record container volumes and added that "Jaxport" has capacity to "easily accommodate vessels displaced by congestion at other US ports." Also, Miami-Dade County mayor Danielle Levine Cava said that PortMiami, which is managing record container volume without delays, is ready "to do our part to help global trade move." And a coalition of Florida's 15 seaports cited the state's consumer market of 21 million people in declaring that the Sunshine State's ports "stand ready to offer a supply chain alternative and solution to the congestion seen on the West Coast and elsewhere."

This ship is an example of the new container traffic the Port of Jacksonville is attracting from more congested ports. Photo courtesy of the Jacksonville Port Authority

The Port of Miami is among several ports in the Southeast that combine significant cruise and cargo operations. Photo courtesy of Port Miami

In fact, spillover from jammed ports has boosted business at some southeastern ports. The Port of Mobile announced in October that year-to-date containerized cargo volumes were up 47 percent in part because of "shifts into uncongested gateways" to North American markets. Hapag-Lloyd, one of the world's largest ocean carriers, in November began temporarily rerouting some ships from Savannah to Jacksonville. Another major carrier announced plans to divert some volume from Savannah to Charleston.

Those moves are temporary and generally do not involve enough cargo to materially affect a port's long-term operations. Shipping patterns don't generally change abruptly, as carriers often operate under long-term commitments to take certain cargo to specific ports, and those commitments often encompass trucking, railroads, and warehousing services. "You can't just pick up and move that overnight," Christian said.

What is possible, though, is to try to negotiate incremental adjustments when shippers renew contracts. So while a shipper or cargo owner such as a major retailer may not divert an entire vessel full of goods from, say, Long Beach or Houston to New Orleans, it might drop a little less cargo in one of those ports and shift a fraction of a ship's load to the Crescent City.

"We're starting to get some traction with that," said Todd Rives, chief commercial officer at the Port of New Orleans. What's more, he figures Port NOLA could benefit from longer-term adjustments meant to guard against future supply chain disruptions. For instance, Rives thinks some apparel manufacturing is migrating from Asia to Latin America, a shift that could create the need to transport products between Latin America and the United States and allow New Orleans to exploit its proximity to Latin America.

"We're starting to see some individual movement by companies saying they can't put everything in China or Southeast Asia, so they may need something closer to the US to ensure regular delivery," Rives said. "I think it's happening today."

By Charles Davidson, staff writer for Economy Matters. Sarah Arteaga, director of the Regional Economic Information Network at the Atlanta Fed's Jacksonville Branch, also contributed to this story.