Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic (third from right) looks over a scale

model of Tampa's downtown. Photo by Ted Pio Roda

Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic (third from right) looks over a scale

model of Tampa's downtown. Photo by Ted Pio Roda

Just a Tom Brady pass across Dale Mabry Highway from the Tampa Bay Buccaneers' stadium sits a hospital whose patients are always OK. Well, sort of. It's actually a simulated hospital, and the "patients" are remarkably lifelike mannequins under the care of some 500 nursing and health sciences students at Hillsborough Community College. The smart dummies' vital signs fluctuate in response to the students' interventions as instructors observe from behind one-way glass and cameras record the work. Later, students and faculty analyze video like coaches and players across the street dissect game video.

One thing they won't see is a dummy "dying." "We don't let the mannequins die," said Leif Penrose, dean of the college's health sciences program, which is housed in an immaculate new three-story building.

Inside a room at Hillsborough Community College, where students acquire

hospital skills. Photo by Ted Pio Roda

Inside a room at Hillsborough Community College, where students acquire

hospital skills. Photo by Ted Pio Roda

"Death" would be traumatic and dispiriting for the students, Penrose explained. He dares not discourage aspiring nurses and emergency medical technicians amid a severe shortage of health sciences professionals in Tampa and across the country. So scarce are qualified nurses that local hospitals pay up to $300 an hour for traveling nurses, according to Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta contacts in the health care industry.

The health sciences program at Hillsborough was but one stop, albeit a memorable one, on a busy agenda as President Raphael Bostic and other Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta officials recently visited the Tampa-St. Petersburg metropolitan area to learn firsthand about the challenges and opportunities in one of the Southeast's bustling metropolitan economies. (One major challenge neither the Atlanta Fed officials nor their hosts could have foreseen was recovery from Hurricane Ian. Though the Tampa Bay area avoided the worst effects, the storm caused more than 100 fatalities, according to media reports, and extensive property damage in Florida.)

The community college offered a window into a workforce development system that nationwide is straining to boost labor supply, as job openings continue to outnumber available workers by nearly two to one. This imbalance in labor supply and demand is among the factors contributing to high inflation.

Fed officials seek enhanced understanding of local economies

Becoming immersed in a local economy is critical to understanding real-time, real-world conditions that affect people differently across geographies and demographics, Bostic emphasizes.

These visits also present an opportunity for Bostic to discuss Atlanta Fed data and tools. For example, in Tampa and St. Pete he mentioned a guide to jobs that pay more than the national median wage but don't require a bachelor's degree—the Opportunity Occupations Monitor—and the Advancing Careers for Low-Income Families initiative, the Atlanta Fed's suite of tools designed to help families navigate circumstances when career advancement puts them above the income eligibility threshold for public assistance programs.

"The only way to understand a place is to be there"

"Our district is so diverse," Bostic said of an area that encompasses Florida, Alabama, Georgia, east Tennessee, and the southern halves of Louisiana and Mississippi. "We have parts of Appalachia, a lot of rural expanses including the Black Belt, and metro areas like Miami, Atlanta, Nashville, New Orleans, and Tampa Bay—all very different places. The only way we truly understand a place is to be there and talk with people and really try to get our heads around it."

Bostic often explains the macroeconomy as a collection of many smaller economies. In Tampa and St. Petersburg, Atlanta Fed visitors got a multifaceted look at one such economy that typifies Sun Belt metropolises that—despite rapid growth and general prosperity—grapple with issues rooted in economic inequality, like a dearth of affordable housing. In the Tampa Bay area, the Atlanta Fed group heard not only from workforce development leaders, but also corporate executives, small business owners, elected officials, advocates for low- and moderate-income communities, and economic development specialists. Those groups included members of the boards of directors of the Bank's Jacksonville and Miami branches.

The trip was Bostic's first visit to Tampa Bay. He traveled with Atlanta Fed staff from Jacksonville and Miami who gather economic information to inform monetary policymaking and others who advise local community development officials and research issues affecting mainly low- and moderate-income communities.

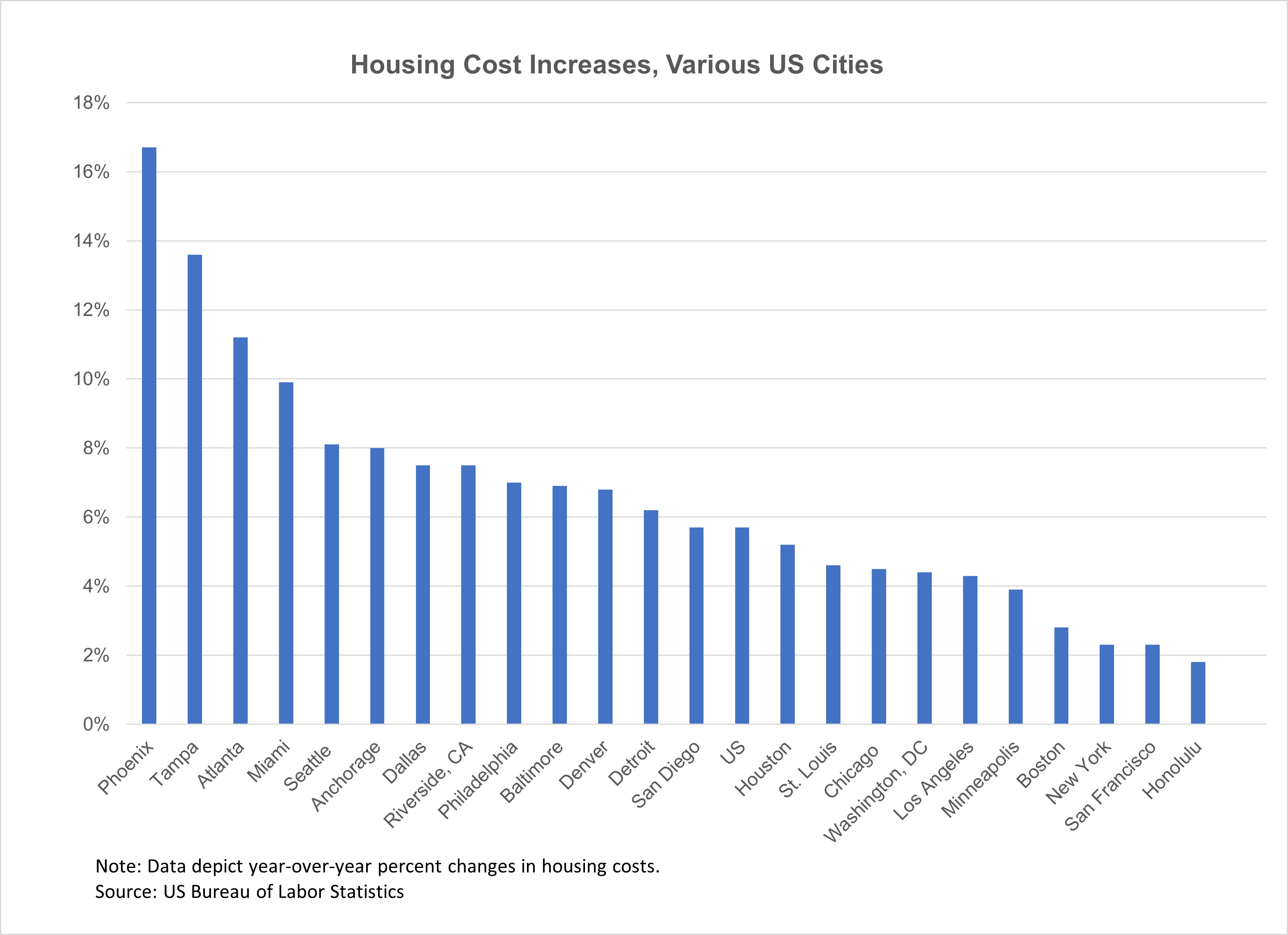

Amid a typically Floridian combination of sunshine and thunderstorms, the central bank staff heard a few themes emerge from numerous conversations. Perhaps the most common refrain was that, like most metro areas, Tampa Bay suffers a shortage of housing affordable to low- and middle-wage workers, and the data reinforce the anecdotes. Among 23 metropolitan areas for which the US Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes local inflation statistics, only Phoenix in June and July had higher inflation for shelter than the Tampa Bay area (see the chart). The situation is so acute that one executive told the Atlanta Fed that his company is experimenting with providing housing for employees so they can live nearer to work.

The Tampa Bay area also has a scarcity of not only health care professionals but also health sciences instructors, who typically earn more working at hospitals than they do teaching. Complicating the workforce issues, many residents of the Tampa Bay region who most need skills training lack access to training and are unaware of the availability of training programs and financial aid.

Moreover, public transportation across the Tampa metro is not extensive, which can make it difficult for lower-wage workers in particular to reach jobs that are often clustered far from their neighborhoods. This physical separation is worsened by rising home values, fueled in part by affluent newcomers from pricier locales, that force people to move still farther from jobs.

Finally, business leaders described how more immediate and national economic concerns—including snarled supply chains and rising prices for items as varied as machine parts and dirt used to prepare residential construction sites—are affecting them.

Tackling economic concerns and revitalizing a neighborhood

To be sure, the Tampa Bay area shares many of its economic concerns, including its workforce issues and dearth of affordable housing, with the rest of the country. To address concerns stemming largely from economic disparities, many economic developers are stressing inclusive growth and opportunity. In Tampa, that includes the city's Equal Business Opportunity program, which aims to connect small, women- and minority-owned businesses with city contracts. The number of firms certified to participate in the program increased by more than a third from the 2018 to 2021 fiscal years, to 1,553.

Tampa mayor Jane Castor described a multi-pronged approach to ease the city's affordable housing crisis, including studying houses produced by 3-D printers.

Across the bay in St. Petersburg, officials are building on the city's vibrant arts scene to support ambitious plans to revitalize an area that includes the largely Black neighborhood that has been gutted by highway and stadium construction during the past half-century.

Bostic meets with St. Petersburg mayor Ken Welch. Photo by Ted Pio Roda

Bostic meets with St. Petersburg mayor Ken Welch. Photo by Ted Pio Roda

Among other positive signs, St. Petersburg community leaders noted dramatic improvements in high school graduation rates among Black males. The Atlanta Fed groups also learned about a workforce development program in the city that recently found jobs for 15 people who had been incarcerated.

Finding the cool factor

Despite the long-term economic concerns Tampa is confronting, the area is flourishing in other important respects. The metropolitan area's job growth surpasses even the vigorous rate of national employment growth. In recent months, the local unemployment rate has hovered around a minuscule 2.5 percent.

Bostic speaks with Tampa mayor Jane Castor. Photo by Ted Pio Roda

Bostic speaks with Tampa mayor Jane Castor. Photo by Ted Pio Roda

And people are earning more money. Median household income in Hillsborough (Tampa) and Pinellas (St. Petersburg) Counties soared nearly 20 percent in nominal terms from 2017 to 2020, according to the latest data from the US Census Bureau, far outpacing national and state increases.

Furthermore, Tampa is enjoying a renaissance, physically and reputationally. At the heart of the resurgence is a sleek $3.5 billion complex of residential, office, and commercial buildings atop what was 56 acres of parking lots near Port Tampa Bay. The Water Street project is developed and managed by Strategic Property Partners, a firm backed by Cascade Investment Group Inc., which is owned by Bill Gates, and Jeffrey Vinik, owner of the Tampa Bay Lightning National Hockey League team that plays a few blocks away.

Water Street boasts innovative architecture, including a building exterior meant to evoke a coral reef. Its condos offer panoramic views of Hillsborough Bay, the class A office space attracts tech companies, and Tampa's first five-star hotel will open this year. Last year, Water Street opened the first speculative high-rise office tower in Tampa in 25 years. Copious amenities include elevators that reportedly zip up and down at 700 feet per minute (nearly eight miles an hour).

Water Street is not Tampa's only gleaming new development. The city's booming downtown condo market recently scored a splashy spread in the Wall Street Journal headlined, "Once Known as the Land of Hooters and ‘Magic Mike,' Tampa Has Discovered Its Cool Factor."

It's one thing to read about a city's cool factor or workforce challenges. It's another to see the health sciences training center and trendy condos for yourself. That's why Bostic and his team traveled to Tampa-St. Petersburg, and why they'll continue traveling the Southeast.