Raphael Bostic

President and Chief Executive Officer

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

Public Affairs Research Council of Alabama Annual Meeting

Birmingham, Alabama

February 15, 2019

- Atlanta Fed president and CEO Raphael Bostic, at the Public Affairs Research Council of Alabama annual meeting in Birmingham, discusses why effective workforce development is essential to economic mobility and resilience.

- Bostic points out that the Sixth Federal Reserve District is doing well overall but has a diversity of economies. Places such as Atlanta, Orlando, and Nashville rank among the worst in terms of economic mobility for locals and natives.

- Bostic believes workforce development can play a central role by helping individuals build their knowledge and skills and make a decent living. The results are higher tax receipts and lower spending on public assistance, incarceration, and other programs.

- Bostic says a fundamental feature of workforce development is the capacity and commitment to ensure that people who face barriers to employment have access to effective training, employment, and support for job retention and career advancement.

- Another fundamental feature of workforce development, according to Bostic, is aligning education and training programs with real business needs.

- Bostic says that a successful workforce development system matters to the Fed because achieving its mandated goal of maximizing employment depends on broad access to economic opportunity.

Good morning. Thanks, Nancy, for the kind introduction. Thank you, PARCA, for inviting me, and thanks for the important work you do. I'm flattered to be asked to speak alongside Governor Kay Ivey and Chauncy Lennon of the Lumina Foundation.

And kudos to you all for braving the road work to get here. Living in Atlanta, I don't know anything about traffic problems.

Before I get to the meat of the topic, let me recognize a few other folks. If you don't already know our Birmingham regional executive, Anoop Mishra, then you should. Anoop keeps me plugged in to conditions on the ground throughout Alabama. That is key to the Fed's vital connection with Main Street. Welcome also to former Atlanta Fed board chair Larkin Martin, Birmingham Branch board members Brian Hamilton and David Benck, and former Birmingham board member Macke Mauldin. Larkin and Macke serve on the executive committee of PARCA's board.

I've visited Birmingham several times in nearly two years at the Atlanta Fed, and it's always a pleasure. You exemplify what I find most hopeful across the Southeast: a passionate commitment to your community.

Now, the theme of the day is workforce development. I'd like to talk about why we view effective workforce development as essential to economic mobility and resilience in Alabama and the Southeast. Within that framework, I'll explore two fundamental features of a successful workforce development system. First is the capacity and commitment to ensure that people who face barriers to employment have access to effective training, employment, and support for job retention and career advancement. Second, I'll discuss why it is crucial to align education and training programs with real business needs. I will conclude with broader thoughts on why investment in workforce development is so important—for employers, for workers, and for the broader community.

Please keep in mind that these thoughts are strictly my own. I do not speak for my colleagues at the Atlanta Fed or for the Federal Open Market Committee, or FOMC.

Southeast a mosaic of many economies

Let me begin with a few observations on the regional economy. The Sixth Federal Reserve District is in many ways a microcosm of the country. For those who may not know, the district includes Alabama, Florida, Georgia, the southern halves of Louisiana and Mississippi, and the eastern two-thirds of Tennessee.

On the whole, the district is doing well, with some standout markets. The unemployment rate here in Birmingham, for example, is below the national rate. Employment in Nashville and Atlanta has grown faster than in the nation as a whole through much of the recovery.

But look closer, and you'll see a great diversity of economies. Even in places with strong growth and numerous job openings, individuals struggle with unemployment and then face barriers when they try to return to work. While many of our metropolitan areas are magnets for newcomers, places such as Atlanta, Orlando, and Nashville rank among the worst in terms of economic mobility for locals and natives. By economic mobility, I mean, essentially, the ability of someone born on the lower rungs of the socioeconomic ladder to move up.

I've traveled extensively across the Southeast in the past two years, and I can tell you virtually no one is living the national averages. Each distinct economy has its own opportunities and challenges, which should shape the strategy of a workforce development system. Broadly improving economic mobility is a daunting task. But we at the Atlanta Fed believe workforce development can play a central role by helping individuals build their human capital—their knowledge and skills—and make a decent living for themselves and their families. The more people who can do that, the better for all of us. The results are higher tax receipts and lower spending on public assistance, incarceration, and other programs focused mainly on the unemployed or underemployed.

Tailoring workforce development strategies to local conditions

So what can workforce development do to help achieve these results? Well, the first step is to tailor successful strategies to a regional and even local context. After all, a job training program that works in New York City during a booming economy may not work in a small, less vibrant southern city.

Let me say a bit about the regional labor market. The labor force participation rate—particularly for individuals between their mid-20s and mid-50s—is lower in the Southeast than in the rest of the country. Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi have especially low rates. In these three states, an unusually large share of people report that they don't participate in the job market because they are too sick or disabled to work, according to Atlanta Fed research. Interestingly, the prevalence of disability and illness in Alabama is higher than in most states across all ages, non-Hispanic ethnicities, and education levels, and in both urban and rural areas. If Alabama's labor force participation rate were closer to the national level, then another 200,000 people would become part of the state's workforce, which could help resolve what are projected to be fairly serious labor shortages in the coming years.

While relatively fewer working-age adults are participating in the labor force, businesses are having trouble hiring. According to our research, about two-thirds of firms have difficulty hiring for jobs that don't require a bachelor's degree. The number is slightly higher for jobs requiring a four-year degree. Regardless of the education level businesses need, companies in rural areas are more likely than those in urban areas to have trouble hiring. The two most frequently reported reasons for hiring difficulty are (1) too few applicants and (2), for those who do apply, a lack of job-specific skills, education, or experience.

We're hearing the same feedback from business leaders. Workers are quitting to take better-paying jobs at an increasing rate, yet companies say it is taking longer to fill vacancies.

Why are these facts about the labor force relevant? Well, growth in the labor force is one of two fundamental ingredients in GDP growth, alongside labor productivity. It follows, then, that one approach to boosting economic growth is increasing the number of individuals in the labor force and equipping those individuals with the skills they need for their occupation or industry.

Workforce development must reach those who most need it

Relatively low labor force participation and hiring difficulties also point to the central role of the 21st century workforce development system: improving economic opportunity, especially for those who face the greatest difficulties in the labor market, and meeting the needs of businesses and society for a highly skilled and competitive workforce.

A work-based learning program in Augusta, Georgia, achieves both of those standards. Reaching Potential through Manufacturing, or RPM, is a partnership between the Richmond County School System and Textron Specialized Vehicles, which makes golf carts and other vehicles. Textron wanted to recruit a skilled workforce, and the school system wanted to improve academic and employment outcomes for at-risk and low-income students. The result was a program that combines traditional high school courses, on-the-job training, soft skills development, mentoring, and employment opportunities.

Students become part-time Textron employees. They work four-hour shifts while they take classes either at school or on site. Textron actually built classrooms and teachers' offices at its manufacturing facility. Textron pays the students and provides meals, transportation, and tutoring. The average attendance rate for the program's first year was 93 percent. The company hired nine of 24 students from the program's first class and helped additional graduates find jobs with other local businesses. That may sound like a small number, but keep in mind these are students who otherwise stood a good chance of not even graduating from high school.

RPM is a great example of a business and a school system collaborating to improve outcomes for young people facing significant barriers to employment.

More cases like this, as well as insights from more than 100 workforce development experts, represent the bulk of a three-volume compendium titled Investing in America's Workforce. A collaboration of—bear with me here—the Federal Reserve, the John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce Development at Rutgers University, the Ray Marshall Center of the Lyndon B. Johnson School at the University of Texas, and the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, the series highlights approaches to improve programs and systems to create an effective 21st century workforce development system.

You can download the book for free at investinwork.org.

The book covers many workforce development topics, but I want to stick to highlighting strategies that can help those who face barriers to employment.

For instance, a section of the book focuses on labor market challenges and opportunities for people with physical and intellectual disabilities and chronic health conditions. Every year, medical conditions cause many Americans to lose their jobs or drop out of the workforce. We've discussed what a sizable concern this is in Alabama. With the right set of early interventions, at least some of these workers could remain on the job. The book also includes targeted workforce development strategies for veterans, formerly incarcerated individuals, and other groups who face barriers to employment.

The importance of alignment

Let me now turn to the second feature of a successful workforce development program: alignment. Ensuring that educators and trainers teach the skills that businesses say they need may sound simple, but doing it well remains a challenge. The good news is that rigorous evidence and experience are building a case for several work-based learning approaches.

Take apprenticeships, which link paid on-the-job training and instruction focused on a particular job. This training and instruction lead to an industry-recognized credential that improves the apprentice's employability. Evidence suggests that apprenticeships increase earnings for workers and help businesses efficiently recruit and develop talent. It's a successful and popular model, but how do we ensure more students and businesses participate? South Carolina's Apprenticeship Carolina program shows one way to do it.

The program offers eligible businesses a $1,000 tax credit for each registered apprentice, which creates an incentive for businesses to participate. But its design is also based on the recognition that starting and running an apprenticeship is not always easy. To help, Apprenticeship Carolina uses regional apprenticeship consultants, who help businesses design and manage their individual apprenticeship programs.

Apprenticeship Carolina is working. Since 2007, the number of programs run by individual businesses has grown from 90 to more than 900, while the number of active apprentices has soared from 800 to more than 30,000.

Why investment in workforce development matters

Access and alignment are two important features that promote a successful workforce development system, and we are constantly on the lookout for more. I'd like to conclude by telling you why this is so important to me and to the Federal Reserve. This matters to us at the Fed because achieving our mandated goal of maximizing employment depends on broad access to economic opportunity.

Certainly, labor market success will vary depending on individuals' actions and abilities. But these outcomes should not be predetermined by a person's socioeconomic background, gender, or race. Without equal access to opportunity, the country squanders economic potential and limits the possibilities of its people.

Americans have long extolled the relationship between hard work and economic mobility and resilience: work hard, and you can get ahead. We believe children should have a chance to do better than their parents. We believe if you experience an economic hardship like losing a job, that hardship should not become permanent. Few Americans would dispute these values. But when we examine whether we are living up to them, the evidence is sobering. Harvard's Raj Chetty and his colleagues found that just half of Americans born in 1984 earn more than their parents. That is down dramatically from 92 percent of Americans born in 1940.

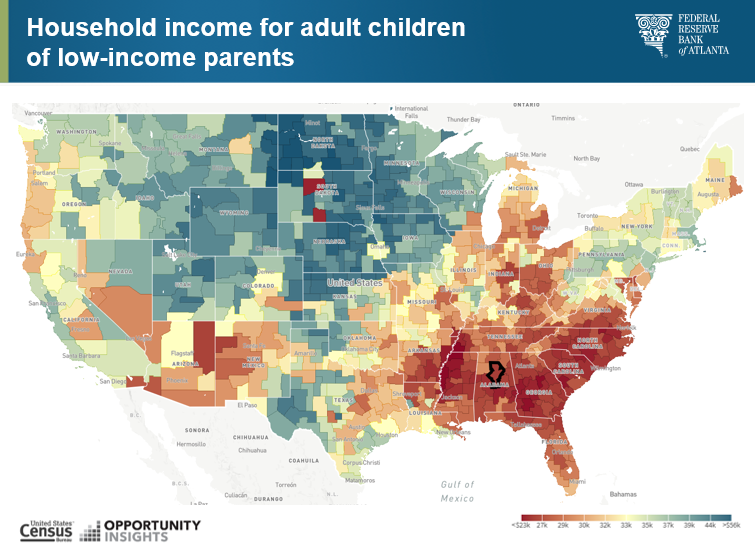

You can see from this map that our region fares poorly in economic mobility. It shows the average household income for adult children of low-income parents. The red color so prevalent in the South means that children born to low-income parents here have lower incomes as adults relative to children born in other areas of the country into similar economic conditions.

These stark differences compel us to reflect on the forces that drive economic mobility and resilience, and to ask whether all Americans have equitable access to these drivers. Workforce development is a critical driver. Clearly, the challenges in building a workforce for the 21st century economy are formidable. But I see plenty of promise.

Programs like Apprenticeship Carolina and RPM are being replicated across the region. Alabama is among several southern states that have created multi-agency leadership groups to guide workforce development policies. I believe a critical mass of knowledge and will is solidifying around the need to build effective workforce development systems across the Southeast. Some of this will not happen without significant investment. Yet the cost of not doing it is far steeper.

As we go forward with workforce programs and systems, please know that one person can make a difference in helping someone find doorways to opportunity that are not always apparent. We at the Atlanta Fed look forward to working with you as you help others find these doorways.