Raphael Bostic

President and Chief Executive Officer

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

Peterson Institute for International Economics

October 12, 2021

Key Points

- Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic speaks live to the Peterson Institute for International Economics on inflation on October 12, 2021.

- Bostic says the pandemic has turned inflation on its head. The elevated inflation dynamics today are very different from what they were in the months prior to the pandemic.

- Bostic says he and the Atlanta Fed believe that "episodic" better describes pandemic-induced price swings than "transitory." By this, he means these price changes are tied specifically to the presence of the pandemic and will eventually unwind by themselves.

- He points out, though, that it is becoming increasingly clear that the intense and widespread supply chain disruptions that have animated price pressures will not be brief.

- Bostic believes the real danger is that the longer the supply bottlenecks and attendant price pressures last, the more likely they will shape the expectations of consumers and businesspeople, shifting their views on pricing and wages in particular.

- Bostic stresses that one of the overarching themes of the Federal Open Market Committee is data dependence. It is through this lens that he views flexible average inflation targeting, or FAIT.

- Bostic believes current conditions argue for a removal of the Committee's emergency monetary policy stance, starting with the reduction of monthly asset purchases.

Good afternoon. I have long admired the important work the Peterson Institute does, so it's a pleasure and an honor to be with you.

Anyone who doesn't want to live in interesting times showed up in the wrong century. The COVID pandemic is the second tectonic (major) economic shock in these first 20 years of the 21st century—I'm counting the Great Recession as the first—and it may ultimately prove to be the most profound economic shock in our lifetimes.

One critical economic element the pandemic has turned on its head is inflation. The elevated inflation dynamics we are experiencing today are very different from what they were in the months prior to the pandemic. Moreover, the durability of elevated inflation has become something of a contentious subject, and perhaps some of you have participated in some of these "debates."

Today, I will spend my time with you discussing this extraordinary inflationary environment of recent months and how I am thinking about policy amid that environment.

Before I go further, do keep in mind that these thoughts are my own and do not necessarily reflect the views of my colleagues on the Federal Open Market Committee.

Transitory is a dirty word

You'll notice I brought a prop to the lectern. It's a jar with the word "transitory" written on it. This has become a swear word to my staff and me over the past few months. Say "transitory" and you have to put a dollar in the jar.

My issue is not with the meaning of the word, but with using it to describe current inflation dynamics.

The first definition of that word in the online Merriam-Webster dictionary is "of brief duration" or "temporary." Time is explicitly present in this definition, and I suspect most Americans think of "transitory" that way.

However, the second definition, the one that many economists mean when they say that word, is "tending to pass away" or "not persistent." This definition is more decoupled from the notion of time. And here is where the use of that word further confuses an already confounding time.

The phenomena economists and policymakers are trying to describe are wild price swings among a set of goods and services. These relative price changes resulted mainly from shifts in consumption—toward goods and away from services like travel and dining out—and supply chain disruptions that limited the availability of components such as semiconductors.

Instead of that word, I think "episodic" better describes these pandemic-induced price swings. By episodic, I mean that these price changes are tied specifically to the presence of the pandemic and, once the pandemic is behind us, will eventually unwind, by themselves, without necessarily threatening longer-run price stability. In this sense, then, we might anticipate the prices of rental and used cars, lumber, and other demand-specific items to revert toward their prepandemic levels. Indeed, we have seen the beginnings of such reversions, which some could take as evidence that the use of that word is correct and fully appropriate.

That said, it is becoming increasingly clear that the feature of this episode that has animated price pressures—mainly the intense and widespread supply chain disruptions—will not be brief. Data from multiple sources point to these lasting longer than most initially thought. By this definition, then, the forces are not transitory.

In my view, we are better served by using a word that avoids this inherent conflict, especially when the more colloquial use of the word points to the wrong inference. So my team and I are not going to use that word anymore to describe these issues.

The great distortion and supply chain disruptions

The outsized influence of these episodic price swings creates at least two issues relevant to the inflation outlook.

First, much like movements in gasoline prices, the dramatic price swings of the pandemic can cloud our reading of the current inflation trajectory.

Take August's Consumer Price Index report (and we may get a similar report tomorrow). Core CPI inflation, which excludes food and energy prices, softened during the month, rising just 1.2 percent on an annualized basis. That was its smallest increase since February, and it has prompted some to conclude that inflation risks have begun to diminish.

Not me. I believe evidence is mounting that price pressures have broadened beyond the handful of items most directly connected to supply chain issues or the reopening of the services sector. If we scrutinize that report, we see that three-quarters of the CPI consumer market basket rose at rates higher than 3 percent during August.

This growing inflationary pressure is echoed by the San Francisco Fed's personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price dispersion measures. One particularly striking statistic: in July, roughly half of the PCE market basket weighted by expenditure posted year-over-year growth rates that outpaced their trailing five-year averages by at least two standard deviations. For those who are not statisticians, that means we expect to see these types of growth rates rarely, in a stable inflation environment, that is.

Still, one important takeaway is that a focus on aggregate core inflation misses the clear, and somewhat troubling, evidence of broadening price pressures. Further, this broad-based price pressure is seen in many alternative measures of underlying inflation, a topic I'll revisit in a moment.

The second issue and, in my view, the real danger, is that the longer the supply bottlenecks and attendant price pressures last, the more likely they will shape the expectations of consumers and businesspeople, shifting their views on pricing and wages in particular.

Inflation expectations among businesses and consumers, in fact, have risen this year. Short-run expectations are sharply higher; indeed, the Atlanta Fed's one-year ahead Business Inflation Expectations measure has hit the highest level in the survey's 10-year history.

More importantly, longer-run inflation expectations measures have climbed, with many reaching levels we haven't seen in about a decade.

These upside risks to the inflation outlook bear watching closely. Evidence from Atlanta Fed surveys and regional economic intelligence gathering programs suggests that many businesses anticipate supply chain challenges to linger into the middle of 2022.

The evidence further shows that many firms are already reacting to supply chain challenges in a more structural way. Rather than just waiting out the current supply and production problems, many executives are seeking new or redundant suppliers, changing their inventory systems from "just in time" to "just in case," and taking other steps to insulate themselves from future disruptions of this magnitude. Undoubtedly, many of these efforts involve a tradeoff between efficient, lean production methods and costlier but less vulnerable configurations. But the key point is that we are seeing that some business leaders' expectations about the resilience of their business models have shifted, which introduces the risk that their expectations for other things could shift as well.

The tools for tracking inflation expectations have advanced

We have not seen this sort of broad-based and sudden surge in inflation readings since the Great Inflation of the 1970s. Now, before I go further, let me make it very clear that I think the conditions and risks today are quite different from that episode.

But this era is relevant for today's discussion because monetary policymakers learned a lot from it, and today we have better tools to understand inflation expectations.

Economists only began to appreciate the critical role of expectations in the late 1960s and early '70s. In those days, the best data came from a twice-a-year survey of economists, not actual price setters. The University of Michigan's survey of consumers' inflation expectations, as we know them today, didn't come along until the late 1970s.

On the business side, today we similarly have the Atlanta Fed's Business Inflation Expectations Survey. But I will emphasize that we're still learning. Indeed, our BIE survey is only 10 years old, and is just now beginning to yield enough data for us to identify meaningful historical patterns and wrestle with what they tell us.

My key takeaway for you here is that we at the Atlanta Fed and in the Federal Reserve System are intently monitoring data and anecdotal evidence to get an early sense of when trends along important dimensions are emerging. At my bank, we have a variety of surveys, metrics, tools, and intelligence gathered from price-setters across the Southeast to keep tabs on threats to underlying price stability.

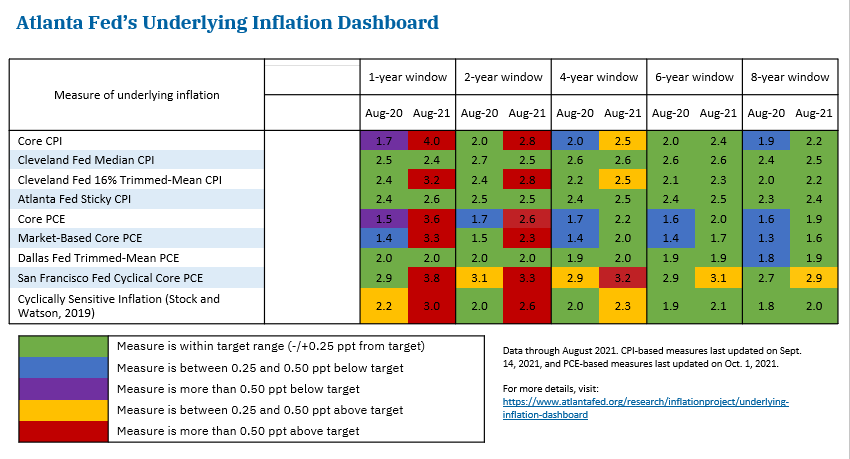

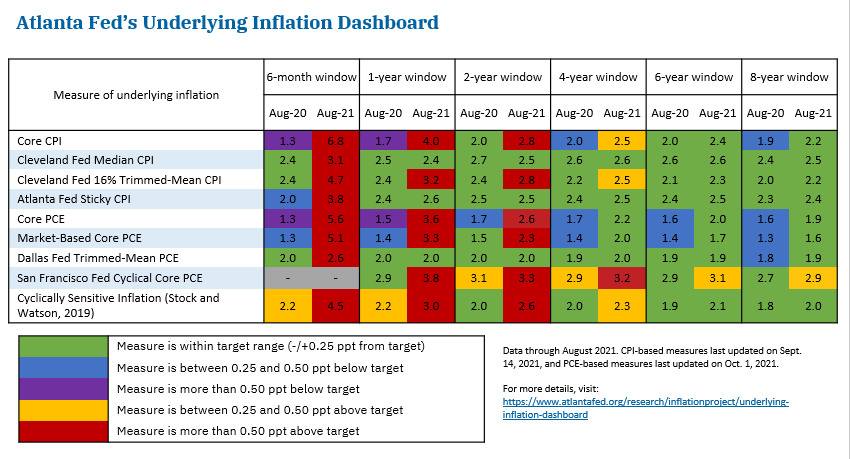

One tool I'd like to highlight is our Underlying Inflation Dashboard. It is a collection of nine alternative price statistics that broaden our view—and hopefully the views of others—ensuring that we do not get too wedded to conclusions based on any one inflation metric. I encourage you to check it out on our website if you haven't already.

I mention the dashboard because I'm going to use it here in a discussion of our monetary policy framework.

What do we mean by "average" and "some time"?

One of the overarching themes in my time on the FOMC has been data dependence. This theme is top of mind, in part because the past decade taught us that preemptive, model-based actions may have prevented many potential workers from participating robustly in the economy.

And it is through this lens that I view flexible average inflation targeting, whose acronym is FAIT and which I pronounce as "fate."

You all know the FOMC's Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy commits us to achieving "inflation that averages 2 percent over time." The statement continues that "following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time."

The Committee left "average" and "some time" loosely defined. In my opinion, it was appropriate to provide such a definition given that it would be unwise to lock the Committee into a rigid policy approach knowing that the economy will likely encounter volatile environments over time, such as the one we're living through.

That said, it is obviously important that we think hard and debate precisely how the Committee's metrics should be interpreted. One place to look to inform that debate would be the analytical work that preceded the policy framework discussions, particularly a working paper titled "Alternative Strategies: How Do They Work? How Might They Help?" by several Fed economists that explores several possible strategies for implementing a FAIT policy.

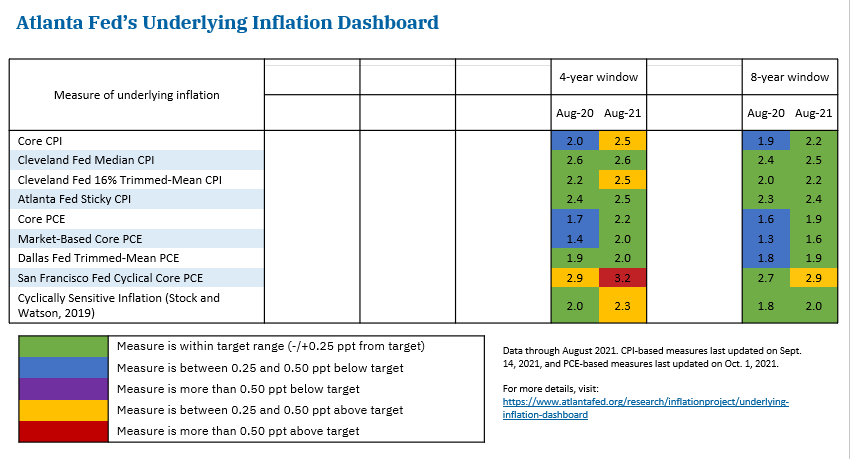

This paper and other work by economists within and outside the Fed indicate that windows ranging from four years to eight years can make sense. My staff ran the numbers for various scenarios through our Underlying Inflation Dashboard and got interesting results.

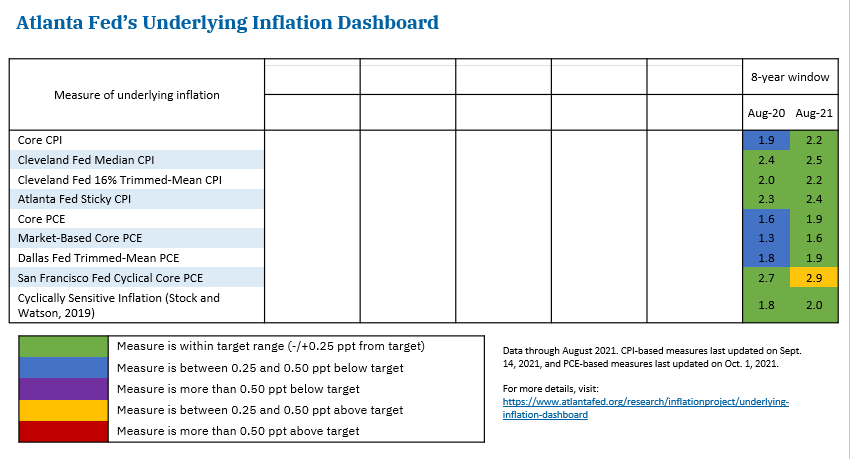

Let's start on the long end. The table shows the eight-year annualized growth rate for the core PCE and CPI, trimmed-mean inflation statistics, the Atlanta Fed's Sticky Price CPI, and other measures tied to the cycle sensitivity of price changes. The two columns display the most recent data, August 2021, and averages calculated as of a year ago, August 2020. Each cell is color-coded to show how close it is to signaling price stability over that horizon. For each measure, green corresponds to being within a quarter percentage point of a reading consistent with core PCE inflation of 2 percent. Blue and yellow are 25 to 50 basis points below and above target, respectively, while red is more than 50 basis points above target and purple is 50 basis points below.

As of August 2021, all but one of the measures of underlying inflation we track were green (within 25 basis points of the 2 percent target) over an eight-year average. And core PCE inflation snuggled up to within 10 basis points of 2 percent over that horizon, up from 1.6 percent a year prior. Even by the eight-year standard, the longer of the relevant time windows, underlying inflation is close to averaging 2 percent.

At the shorter end of the proposed FAIT averaging window, four years, we see that indeed, we have met or exceeded the FAIT standards this year.

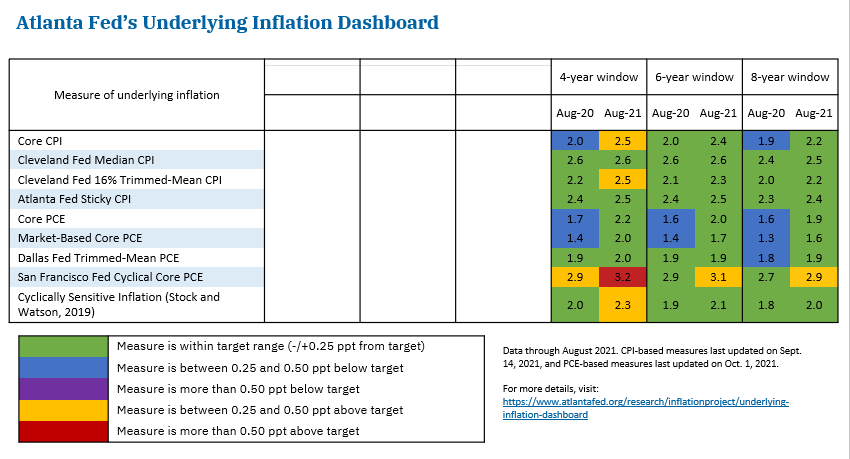

If you want to quibble with four- or eight-year windows, then let's split the difference. As you can see, we must draw the same conclusion whether we look at a four- or a six-year window.

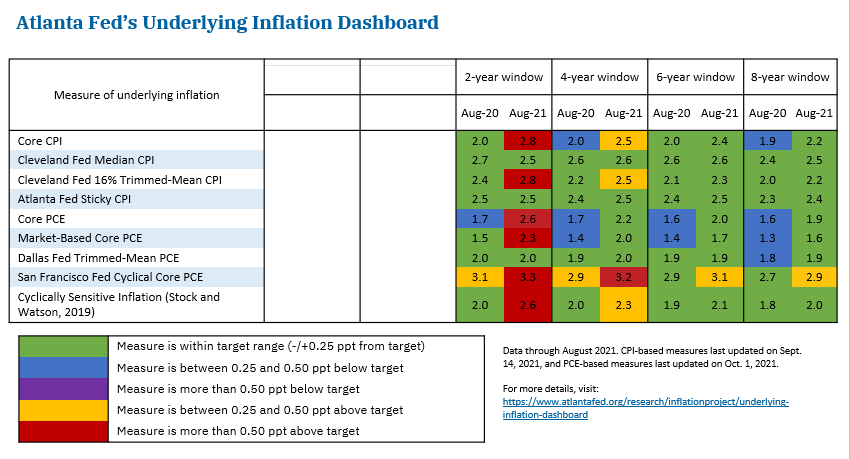

Closing in on the more recent time periods, two years, one year, six months, we can see more red. In essence, all these underlying inflation measures are pointing to growing, broad-based inflation essentially at or above our target.

The upshot, for me, is pretty obvious. If highly accommodative monetary policy is meant to correct past inflation shortfalls, then we have accomplished that mission.

But that conclusion then gives rise to another important question: what constitutes an overshoot of the 2 percent target? What is "moderately above 2 percent"?

I'm not terribly worried if we are averaging 2.25 percent, even over a longer period, say a six-year window. As I've noted before, where I get concerned is if the trajectory of inflation is steep and appears likely to be persistent enough to risk unanchoring long-run inflation expectations.

The inflation outlook

However we choose to analyze the data, I've seen enough to conclude that underlying inflation is indeed above the Committee's 2 percent objective. And upward price pressures are expanding beyond a handful of relative prices elevated by idiosyncratic forces.

The food services industry is illustrative of price and wage pressures. Inflation in the food away from home category shows signs of persistence, while employee compensation has climbed sharply as restaurant operators struggle to fill open positions. However, the category is representative of broader measures suggesting wages, while rising more briskly, are lagging prices.

Certainly, it's too early to proclaim we are witnessing a wage-price spiral like the one that led to the Great Inflation. But conditions merit watching, and my staff and I are doing just that.

To wrap up, I continue to believe currently elevated inflation is episodic, driven by pandemic conditions such as disruptions in supply chains and labor markets. A major caveat, though, is that the severe and pervasive supply chain issues will probably last longer than most of us initially expected.

Up to now, indicators do not suggest that long-run inflation expectations are dangerously untethered. But the episodic pressures could grind on long enough to unanchor expectations. We will be watching carefully.

In my view, then, the fate—not to be confused with FAIT—of price stability could be on the line in coming months. I think inflation is likely to remain above 2 percent going forward. How far forward I cannot say. But upside risks are salient. I believe the conditions I've described argue for a removal of the Committee's emergency monetary policy stance, starting with the reduction of monthly asset purchases, as we discussed in last month's meeting.

This is our first inflationary cycle under the FOMC's new policy framework. So it is clear to me there's value in communicating how we gauge progress toward our inflation goals and what we view as the appropriate inflation signal on which consumers, businesspeople and markets should focus.

I hope I have shed light on my thinking along those dimensions today.