Raphael Bostic

President and Chief Executive Officer

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

South African Reserve Bank Biennial Conference

Cape Town, South Africa

August 31, 2023

Watch the speech.Key Points

- Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta President and CEO Raphael Bostic discussed challenges in US monetary policymaking at the South African Reserve Bank Biennial Conference in Cape Town.

- Bostic feels the Fed's monetary policy is appropriately restrictive.

- He believes the Federal Open Market Committee should be cautious and patient and let restrictive policy continue to influence the economy, lest the committee risk tightening too much and inflicting unnecessary economic pain.

- However, he does not favor easing policy any time soon.

- Bostic detailed significant progress in lowering inflation. He noted that the Atlanta Fed's Sticky-Price CPI gauge was basically flat in June and July and rose just 0.8 percent annualized over the past three months after excluding food, energy, and shelter prices.

- He believes Atlanta Fed surveys and conversations with price setters signal that the downward momentum of inflation is likely to continue.

- But, he added, the battle is not over, and it is essential that inflation be brought all the way back to the committee's 2 percent target.

- Bostic said the labor market could be cooling faster than headline monthly job growth numbers suggest.

Thank you for having me. It's flattering to be invited. I look forward to learning from you all over the next couple of days and sharing a few thoughts on challenges my colleagues and I face in making monetary policy in the United States.

This conference also is an opportunity to further advance the relationship between the Atlanta Fed and the South African Reserve Bank. Many of you may not know that staff from our survey center are collaborating with colleagues here to construct a study of the payment habits of South African consumers. That project is modeled on a study our Bank leads for the Federal Reserve System, and I hope it can lay the groundwork for more partnerships.

When I was asked to discuss challenges in US monetary policymaking, I figured it was an easy assignment—challenges truly abound. Today I will discuss what in my view are the most important challenges we face right now, which mostly come down to one word: inflation. I'll begin with a word about my current stance on US policy. Then I will detail the progress we have made in lowering the inflation rate, and the adjustments I still want to see to feel absolutely comfortable that the trajectory of inflation is conclusively on a path to 2 percent.

Before I do that, note that I said "in my view," because these are my views alone and not necessarily those of anyone else on the Federal Open Market Committee or at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

Current monetary policy

You no doubt saw that the Committee voted last month to raise the federal funds rate another 25 basis points, to a level of 5 1/4 to 5 1/2 percent. Based on current dynamics in the macroeconomy, I feel policy is appropriately restrictive. I think we should be cautious and patient and let the restrictive policy continue to influence the economy, lest we risk tightening too much and inflicting unnecessary economic pain.

That does not mean I am for easing policy any time soon. Inflation in the United States is still too high. The battle against inflation has seen significant progress. Inflation is well off the very elevated levels we saw in the last year, but it's essential that it be brought all the way back to our target.

We must remain resolute in the campaign for price stability until we see that inflation is conclusively on track toward 2 percent over a reasonable time frame. I believe policy is already restrictive enough to get us there. Should conditions not play out the way I anticipate, and inflation or inflation expectations abruptly reverse course and start climbing, then I would certainly support doing what would be necessary to put the US economy back on a path toward price stability.

Pandemic dynamics still important

I just quickly summed up my policy stance. But formulating policy is hardly a straightforward exercise, particularly in today's environment. The challenges I'll detail still stem mostly from a pandemic the likes of which none of us had experienced.

The US lost 22 million jobs in two months. In the second quarter of 2020, the nation's gross domestic product contracted by 30 percent, similar in magnitude to the Great Depression. The enormous shock was especially vexing because it was utterly unlike a typical economic downturn. It did not result from excesses within the economy but from a worldwide health crisis and significant, necessary measures taken to protect the public.

Amid lockdowns, many homebound Americans unleashed a shopping binge that overwhelmed production arrangements that were already taut due to decades-long efforts to design hyper-efficient, just-in-time supply chains. Limited factory operating hours, and short-staffed ports and transportation systems exacerbated the strain amid lockdowns and other public health constraints.

As COVID caused businesses to shutter and millions became unemployed, the American government responded with trillions in fiscal supports, including direct payments to consumers and businesses. Meanwhile, the FOMC slashed the federal funds rate to near zero and instituted lending facilities and other programs to support households, businesses, and financial markets. We aimed to nurse the economy through the worst of the pandemic downturn and come out the other side with minimal long-term damage.

For the most part, I think we did that.

Employment rebounded more rapidly than anticipated. In just over two years, employment returned to its level on the eve of the pandemic. By comparison, after the Great Recession of 2007–09, it took twice as long to regain far fewer lost jobs.

Along with other factors, the surge in goods spending I mentioned helped spark the biggest inflationary spike the United States had seen in 40 years beginning in the spring of 2021. We expected price pressures to settle once extraordinary pandemic-related supply and demand factors normalized. Turns out it has taken longer than we anticipated for supply-and-demand conditions to return to their longer-term trends.

To combat inflation, the Fed has aggressively tightened monetary policy. We've raised the federal funds rate by 525 basis points over a year-and-a-half. But it's important to put those moves in the proper perspective. Not all those moves represented actual tightening. I view the first 325 to 350 basis points as removing accommodation, and then the subsequent 175 to 200 points as moving policy into restrictive territory.

Inflation on a clear path downward

I am gratified to say the policy tightening has proven effective in helping to lower inflation toward our 2 percent target, as measured by the Personal Consumption Expenditures, or PCE, price index. The decline in inflation has been slow, and I expect that pattern to continue.

For the sake of clarity and because we have it in hand for the month of July, I'm going to cite readings from the other major inflation gauge, the Consumer Price Index, rather than jump back and forth between the two measures. The latest CPI headline number came in at 3.2 percent in July, while core inflation, excluding food and energy, was 4.7 percent, compared to a year earlier. Those are down from a cyclical peak in the headline rate of nearly 9 percent in June of 2022 and the core of about 7 percent last fall.

Focusing on July again, a closer look shows that core CPI for that month rose at just a 1.9 percent annualized rate, matching its increase from June and declining sharply from its annualized growth rate of 5 percent through the first five months of the year.

Those numbers suggest a case could be made that if it were not for stubborn (and lagging) housing services prices, the core CPI would be running at 2.6 percent on a year-over-year basis, and just 1.1 percent over the past three months, a rate that is well below price stability. So, essentially, given the lagging nature of rental prices in the calculation of the CPI—and the PCE for that matter—underlying inflation may well be close to our target already.

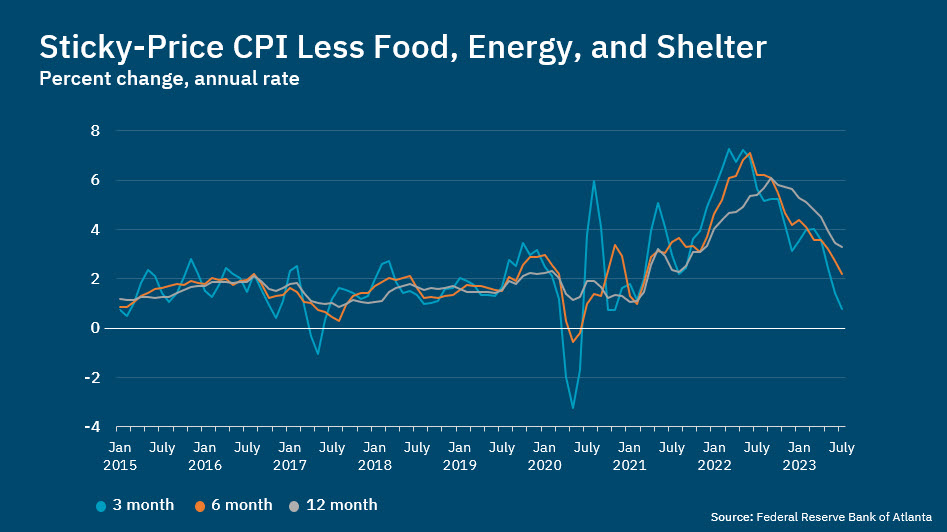

The trend in one alternative measure of inflation, the Sticky-Price CPI developed by my staff, is giving me particular confidence that inflation is headed in the right direction. After excluding food, energy, and shelter prices, the Sticky-Price CPI was basically flat in both June and July and, as the slide shows, has risen just 0.8 percent annualized over the past three months. Note that the lines in the graphic are all diving toward or even below 2 percent.

The sticky prices in our index include categories like personal care services, trash collection, medical care services, shelter, and education. In total, our sticky-prices basket comprises roughly two-thirds of the entire CPI basket by expenditure weight. Because these prices are typically slow to respond to changing economic conditions, they may contain an embedded inflation-expectation component and thus tend to be good forecasters of inflation two to three years ahead.

Let me describe a final data point that I have focused on for some time now because I think it, too, transmits a meaningful signal about the trajectory of prices. That is the breadth of inflation. The recent shift in the price change distribution has been striking. Over the past three months, on average, just 35 percent of the underlying CPI components, by expenditure weight, rose at rates of 5 percent or more. Granted, this is still higher than the prepandemic average of 15 to 20 percent, but in July of 2022 (just a year ago) the number was about 80 percent. I don't think it's a stretch to call this another marker of significant progress!

The promising evidence is expanding. Still, even a large handful of data points will not prompt us to pop champagne corks just yet, because the economy is still beset by uncertainty and we cannot be completely sanguine about any projections. However, in the remainder of my comments, I will make the case that our restrictive monetary policy stance is having a clear moderating effect on economic activity that should put further downward pressure on prices and thus promote a return to our 2 percent inflation target.

Indeed, I believe Atlanta Fed surveys and numerous conversations with price setters offer convincing signals that the downward momentum of inflation is likely to continue. And I'll note that our surveys and grassroots information channels have a strong track record, so I feel confident in their predictive ability.

I'll start with the outlook for prices.

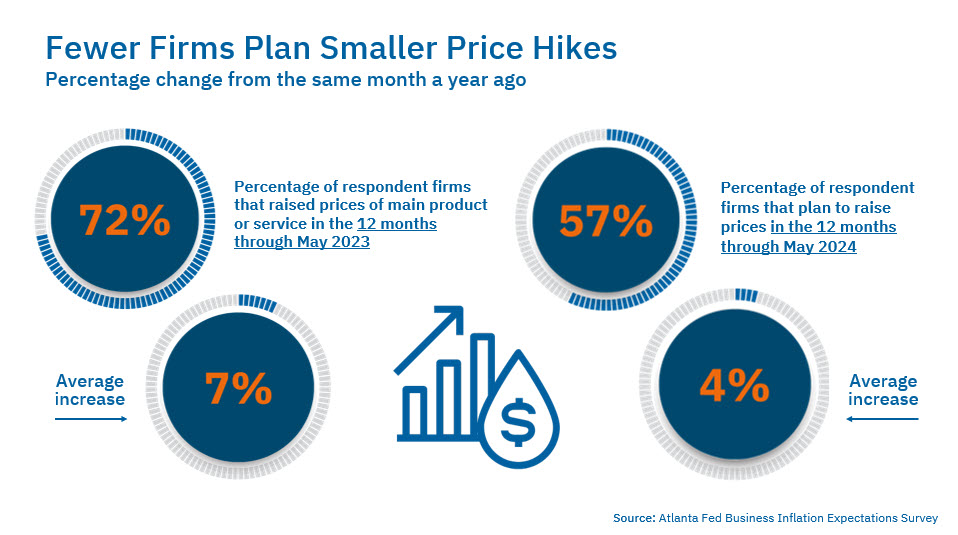

Our Business Inflation Expectations (BIE) survey is a monthly canvass of 200 US companies across industries and firm sizes. In the latest BIE, fewer firms say they plan to continue raising prices, and those that do plan to raise them say they'll do it by smaller amounts. Almost three-quarters (72 percent) of firms reported that they increased prices of their core products or services in the 12 months through May 2023. The average increase was 7 percent. By contrast, for the year ahead, 57 percent told us they intend to raise prices by an average of only 4 percent.

Other surveys in a research collaboration with colleagues at the Cleveland and New York Feds show similar projections of less severe price increases to come. Finally, feedback from field staff in our Regional Economic Information Network, or REIN, offers still more confirmation that peak pricing power has most likely passed.

The anecdotes pointing to diminishing pricing power, and perhaps moderate slowing in economic activity, are supported by preliminary results from the most recent Atlanta Fed Survey of Business Uncertainty, or SBU. In the most recent survey, year-ahead nominal sales growth expectations slowed from 5 percent at the beginning of the year to 3 percent, which is well below the prepandemic average for expected sales growth in the SBU.

Labor market cooling

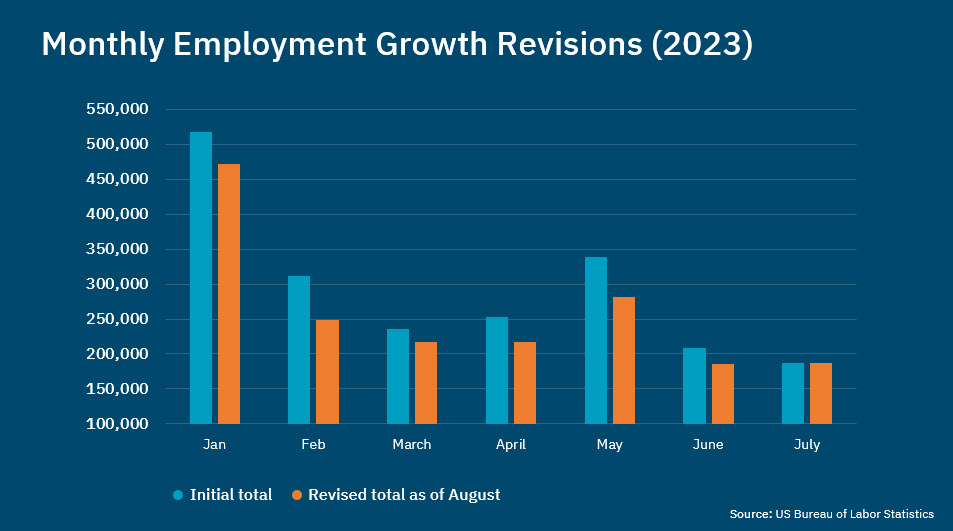

Turning to labor markets, there appears to be a measured cooling afoot there, as well. After the jobs report in May showed a one-month surge in hiring, the June and July reports showed employment growth continuing to moderate, albeit at a slower pace.

I will also point out that for the first six months of this year, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics revised payroll employment growth downward by an average of more than 40,000 jobs a month relative to the initial release, so the labor market was not running quite as hot as we had originally believed. And based on the BLS's preliminary benchmark estimate it looks like employment growth in the first quarter of 2023 will be revised a bit lower still. Furthermore, the job market may be cooling even faster than the headline numbers suggest, as growth in total hours worked has slowed more than growth in employment because of recent increases in part-time work.

Now, let me say a word on wages. Economists are concerned about how much wage pressures are influencing inflation, especially in services prices. To be sure, debate continues about whether wages are a lagging or leading indicator of inflation. I won't settle that question today.

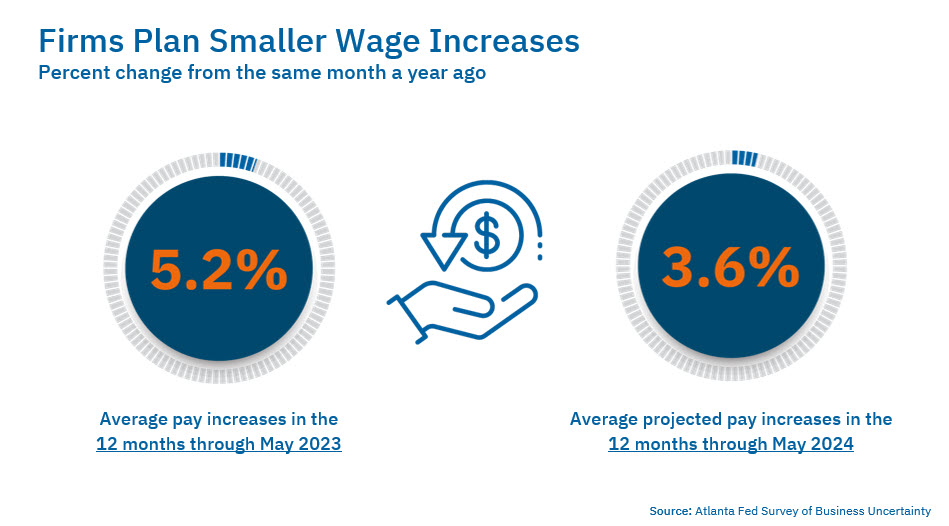

I will say, from the SBU, we detect signs of current and future wage growth moderating. For the 12 months starting in May 2023, the SBU says employers aim to raise wages an average of 3.6 percent, down from last year's 5.2 percent.

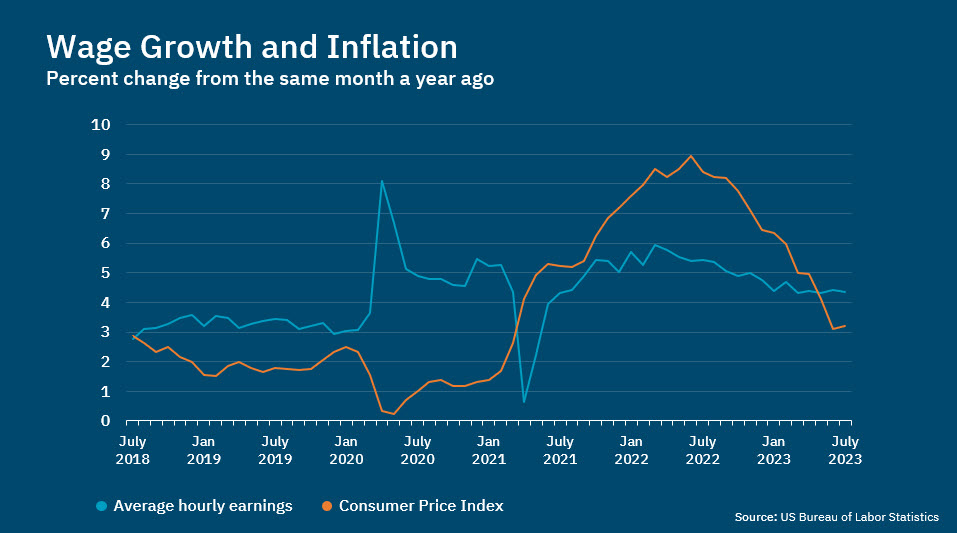

Let me offer a little context. For much of the past couple of years, elevated inflation made real wage growth negative, after positive growth just above 1 percent before COVID. So, I would expect nominal wage growth to exceed inflation for a time as real wage levels revert to the prepandemic growth trend. In fact, over the past three months, average hourly earnings pretty comfortably outpaced inflation, as the slide makes clear.

The upshot is that wage growth is moving back toward normal, which over the long term typically means an equilibrium level roughly in line with productivity growth. As long as firms continue to signal a slowing trajectory on price growth—that is, they are willing to absorb some margin contraction—then real wage growth should not put upward pressure on prices. Our conversations with business leaders confirm that scenario—they are raising pay so their employees' wages catch up with past inflation, and do not anticipate having to raise prices in the future to keep pace with the higher wages. And as I noted, our surveys and conversations make clear that employers plan to taper down those wage hikes to normal prepandemic levels in the coming years. So, I'm not overly concerned that a period of moderate real wage growth will rekindle inflationary pressures.

I've cited evidence that I believe represents a convincing case that the rate of inflation will continue declining toward our objective of 2 percent: reductions in planned price increases, cooling in the labor market, and, ultimately, a measured tempering of economic activity that will bring supply and demand into closer alignment.

Uncertainty is still prevalent

Having said all that, the economic journey ahead is far from assured. We continue to confront a great deal of uncertainty and risk. We emphasize this a lot, but it's worth restating: we don't have historical models to guide us through the shock of the pandemic. So, in important ways we continue to operate in uncharted territory as we aim to restore economy-wide supply and demand to a preCOVID equilibrium. The lingering effects of COVID, heavy corporate and government debt, the war in Ukraine, other possible geopolitical shocks abroad and at home, and extreme weather events are but a few of the risks facing the macroeconomy and, thus, the path to 2 percent inflation.

There are other, more immediate risks we're also watching closely. One lies in the commercial real estate business, particularly the office sector. The trend toward work from home has pinched some office building owners and lenders, especially those with older, less luxurious space. Higher interest rates make it difficult for commercial property owners to refinance debts that they may be having trouble servicing as occupancy rates are falling.

Housing is another important component of the American economy, and there are concerns there, too, mainly involving low inventories of homes for sale. That pushes up prices and squeezes affordability. Rising interest rates play a role here, too, as homeowners are loathe to give up existing low-rate mortgages to sell a home and then buy a different house at today's higher rates.

The banking sector itself remains a source of risk as banks navigate a higher-interest-rate-environment, though by and large the US banking system is sound and well capitalized.

Commercial real estate, housing, and banking are all directly affected by interest rates. As we administer medicine to the economy in the form of tighter monetary policy, the intent is to modulate demand to better align with supply and therefore ease upward pressure on prices. We need to be patient, let the medicine of restrictive monetary policy work its way through the economy, and not reverse course until it's clear that higher inflation is no longer a threat.

Time to be patient, resolute, and cautious

To reiterate, I think the facts I've assembled here argue for a patient, resolute, and cautious approach to monetary policy:

- patient, so that our policy can work through the economy and continue to gently rein in economic activity

- resolute, to hold policy at an appropriately restrictive place for as long as it takes to be certain that inflation is bound for 2 percent

- cautious, because I think we now risk overtightening and inflicting unnecessary damage on the labor market and wider economy. On this last point, we need to be cognizant of "passive tightening," as falling inflation means real interest rates rise even as the nominal rates the Fed influences remain stable.

Should the data not come in as I expect—for example, if inflation or inflation expectations start climbing—and it becomes clear the Committee must tighten further to keep inflation falling, then I would support that. Given widespread economic uncertainty, I do not expect our path from here to the 2 percent inflation objective—the last mile, if you will—to be without curves and bumps.

But we will get there. Be assured I am committed to restoring price stability so that American households can enjoy maximum employment and an economy that works for all, which is a tagline for the Atlanta Fed. When we achieve this, the resultant stable, healthy US economy will be a clear positive for economies around the world. At that point, we can work together to ensure that these economies increasingly work for all people across the globe. I look forward to helping bring that reality closer to fruition.