Raphael Bostic

President and Chief Executive Officer

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

Schwartz Lecture

The New School for Social Research

October 19, 2023

Watch the speech.Key Points

- Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta President and CEO Raphael Bostic delivered the Schwartz Lecture on wealth inequality at the New School for Social Research.

- Bostic called expanding economic opportunity a defining issue of our time and said that is why the pursuit of economic mobility and resilience is a guiding strategy for the Atlanta Fed.

- He explained that monetary policy is not well suited to address particular economic disparities such as wealth inequality.

- But, he added, monetary policy plays an important role in enabling economic expansions and cited the prepandemic expansion, the longest in US history, as an example.

- During that time, the fruits of a strong labor market spread across the population to benefit traditionally marginalized workers, Bostic said. The unemployment rates for Black and Hispanic workers reached all-time lows.

- He detailed how the Federal Open Market Committee adapted to changing economic conditions and kept monetary policy accommodative even as unemployment fell to record low levels, helping to fuel labor market gains.

- Bostic described how the work of the Atlanta Fed's Advancing Careers for Low-Income Families initiative helped inform an expansion of eligibility standards for a Florida public health insurance program for children.

Thank you, Professor Ghilarducci, for the kind introduction. And thanks to everyone at the New School for inviting me to deliver the Schwartz Lecture. It's an honor and a privilege.

Expanding economic opportunity is a defining issue of our time. Because of outright discrimination in some cases and unintended consequences in others, our nation has long squandered too much talent and creativity. We must change that to continue thriving as a people and an economy.

That's why we at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta several years ago embraced the pursuit of economic mobility and resilience, or EMAR for short, as a guiding strategy.

I will detail some of our Bank's EMAR work today, after I discuss the role monetary policy plays—and, importantly, does not play—in confronting economic disparities such as wealth inequality. My remarks will focus on monetary policy's effects on the labor market, as for most of us a good job is a precondition to building wealth.

I'll add that these are my thoughts and do not necessarily reflect those of colleagues in the Federal Reserve System or at the Atlanta Fed.

I won't spend time describing the state of wealth inequality. Teresa outlined the situation well, and I think you all understand it's been a grave problem for decades and defies quick fixes.

Up front, I need to be clear that the Fed operates within statutory constraints. That means we cannot pursue certain activities. We cannot award grants, nor deliver ongoing services to families and communities, nor directly lobby for particular policies.

That is our reality.

The Fed's mandate from the Congress is to pursue price stability and maximum employment. A superficial reading of the mandate might suggest we not concern ourselves at all with economic disparities. After all, our core duty, monetary policy, influences the economy in extremely broad ways and thus is not a direct remedy for economic inequalities.

But such a reading would miss a larger point that stems from the maximum employment side of the mandate, which I interpret as sustained maximum employment.

Let me explain. A quick workable definition of maximum employment says we are charged with creating an environment in which everyone who wants a job can find one. In the shorter run, employment opportunities tend to be constrained by a person's education or training, experience, the availability of jobs where they live, and so on.

But over time, these circumstances can change. People may go to school, get training, and gain new skills. In the longer run, then, sustained maximum employment means everyone has the opportunity to get, not just any job, but gainful employment in a job that is consistent with their full potential.

To achieve sustainable maximum employment, we must foster an economy in which everyone can maximize their human capital and apply their talents to their highest and best use to earn family-supporting incomes. In short, sustainable maximum employment is a more inclusive objective.

So, while monetary policy cannot granularly address persistent ills like wealth inequality, it has a role, and that role is linked to the dual mandate and grounded in the reality that economic disparities limit opportunity for millions of Americans. Limitations for workers limit employment, which limits the economic prospects of businesses, which in turn constrains local, regional, and national economies. Therefore, economic disparities are a concern of the Federal Reserve.

How do we address that concern within our statutory framework? Or, since I've described what we can't do, what can the Fed do?

Monetary policy can feed labor market momentum

As I noted, monetary policy by nature is not suited to target conditions for particular populations or locations. Rather, monetary policy can help create broad conditions conducive to sustaining economic expansions. That is where our policy can contribute to better labor market outcomes for those typically on the margins of the economy and the short end of wealth inequality.

In that vein, I'd like to focus on the late 2010s, the years immediately before the pandemic.

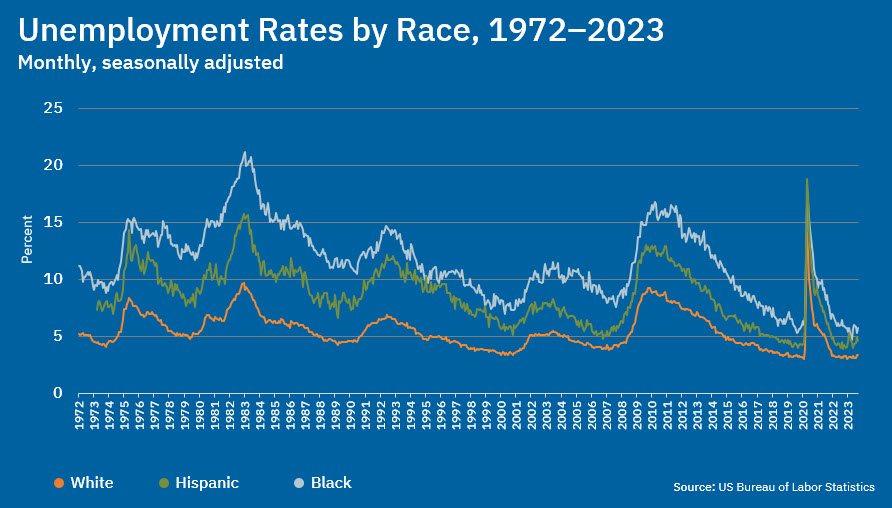

As some of you might recall, this period became part of the longest economic expansion in US history as the fruits of a strong labor market eventually began to spread across the population. The unemployment rates for Black and Hispanic workers reached all-time lows, and the gaps between those rates and the White unemployment rate narrowed to their lowest levels on record.

The decline in Black unemployment was especially strong. In late 2019, it hit its lowest average since the Bureau of Labor Statistics began gathering the relevant data in 1972. As Fed chair Jerome Powell has pointed out, before the pandemic, it appeared those gains would continue.

During those prepandemic years, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) did not default to a policy approach that had proven quite effective over the previous two decades—a formulation that very low unemployment inevitably leads to inflation. Instead, as unemployment kept falling but inflation remained subdued, the Committee let the economy run.

The policy decisions were not obvious. The main policy rate, the federal funds rate, stood at effectively zero for seven years as the economy limped out of the Great Recession. Even before the FOMC began "liftoff" and nudged the rate up in late 2015, various rules-based formulas suggested the rate should be higher.

There were calls from outside the Committee to remove policy accommodation sooner. And Summaries of Economic Projections from that time suggest Committee members anticipated it would be appropriate to raise the federal funds rate sooner and more than it ended up doing.

The Committee moved the policy rate in December 2015 to a range of 0.25 to 0.5 percent. Just a year earlier, the median FOMC member projection had the appropriate rate at 1 percent for 2015. By the end of 2016, the funds rate target was still just 0.5 percent to 0.75 percent; the median Committee projection a year earlier had it at 1.4 percent.

My point: the Committee was willing to adapt to changing economic conditions and reacted to incoming data rather than hewing to projections or long-held conventions about the connection between low unemployment and inflation. And the beneficiaries of the labor market that resulted from the approach were disproportionately the people in the groups on the wrong side of the nation's wealth divide.

I don't want to bog us down with too many numbers, but I think a few data points will clarify how the FOMC's thinking on the relationship between unemployment and the threat of inflation has evolved.

Learning and adapting to changing conditions

First, a little background. Inflation forecasts traditionally have been based on estimates of what economists call the natural rate of unemployment, or "u-star" (or "u*"), and how much upward pressure on prices results when the unemployment rate declines relative to u-star.

Basically, u-star is the unemployment rate consistent in the longer run with the Committee's 2 percent inflation objective. Think of it as an unemployment rate that will neither kindle inflation nor cause widespread disruption for households. There is no observable measure of u-star; we estimate it as best we can.

In the late 2010s, as real unemployment dipped lower and lower and inflation hardly budged, the Committee reduced its estimates of the natural unemployment rate. The median estimate from last month's FOMC meeting is 4 percent, down from 5.5 percent in January 2012, when the Fed last updated its underlying monetary policy framework before 2020.

A difference of 1.5 percentage points over a decade may not sound big. But based on the size of today's labor force, that gap would translate to about 2.5 million additional unemployed people. Had the Committee not been willing to adapt to the ever-changing real economy, we likely would have raised interest rates sooner in the 2010s and perhaps snuffed out employment opportunities for many of our neighbors.

As Powell said in his 2019 speech at Jackson Hole, "Since 2012, declining unemployment has had surprisingly little effect on inflation."

Indeed, the unemployment rate fell from 10 percent in 2012 to under 4 percent when Powell spoke. The longest expansion on record produced an unemployment rate that hovered near 50-year lows for roughly two years, well below most estimates of the sustainable level. Labor force participation also climbed.

One of the reasons those things happened was that from 2010 through 2020, the FOMC never pushed the target for the federal funds rate above a range of 2.25 to 2.5 percent, and inflation remained calm. Monetary policy helped sustain an economic expansion that over time disproportionately benefited people who traditionally are the last to enjoy the fruits of a growing economy.

Research shows Black workers, especially, benefit from long expansions

How do we know this? Research tells us that long expansions disproportionately help traditionally marginalized workers. The literature has established that the Black unemployment rate declines faster than the White rate during expansions, but also rises faster in downturns. That appears to be especially true in the latter stages of economic growth cycles.

One of our economists, Julie Hotchkiss, found that Black workers had just begun making material labor market gains in the late 2010s. In a 2021 paper, Hotchkiss showed that Black workers benefit disproportionately from the momentum of a recovery when the economy is unusually strong and the expansion lasts long enough to bring in those at the margins of the labor force. A 2019 paper by four Fed economists and published by the Brookings Institution found similar results.

On the other hand, research also shows that when the economy cools, disadvantaged workers on average suffer the sharpest setbacks. Hotchkiss, for instance, writes that the sudden onset of the COVID pandemic reversed much of the progress Black workers made in the late 2010s expansion.

Finally, a new working paper from the Federal Reserve Board of Governors finds that, not surprisingly, inequality in labor market outcomes between White and Black workers translates to a meaningful difference in welfare for the two types of households.

A more novel finding from that work concerns the monetary policy framework the Fed adopted in August 2020. I'm not going to do a deep dive on the framework today. But the key for our discussion is that the framework commits the FOMC to set policy based on shortfalls in employment, whereas previously we zeroed in on deviations, which of course would include periods when unsustainably low unemployment, so traditional theory held, threatened to spark inflation.

This new research from the Board of Governors suggests that the Shortfalls rule will bolster economic expansions by holding interest rates lower than they would have been under the previous approach. Specifically, under the new framework, the unemployment rate in a typical expansion will decline by about 0.7 of a percentage point more than it otherwise would.

I'll quote directly from the paper here to avoid ambiguity: "Even though the Shortfalls rule still targets the aggregate unemployment rate gap, it has disproportionately larger benefits for Blacks than for whites in terms of unemployment rates."

Let me reiterate that these benefits accrue from lengthening economic expansions and not from any intervention aimed precisely at racial unemployment gaps. Monetary policy just doesn't work that way.

Educational attainment has been important

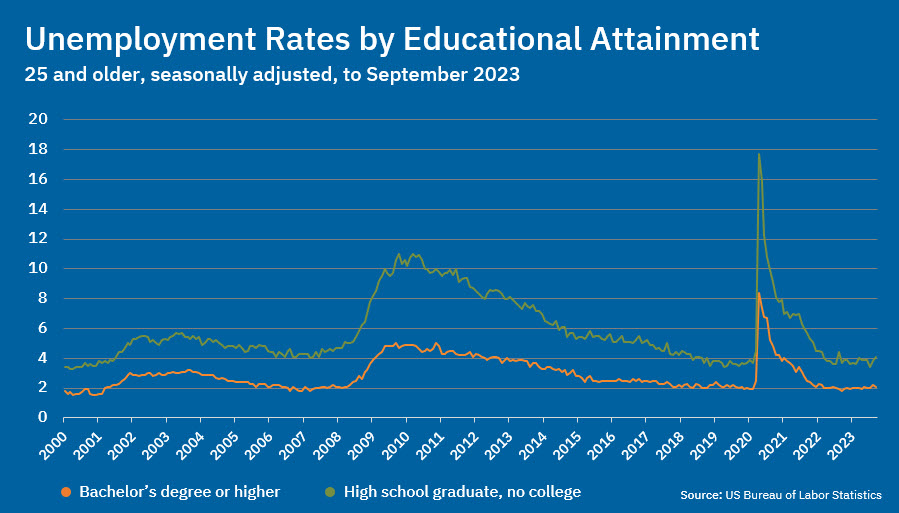

To be sure, monetary policy is not solely or perhaps even mainly responsible for enhancing employment outcomes for disadvantaged workers. A notable factor of late is progress in educational attainment.

Consider college degree attainment rates. You no doubt know that African Americans and Hispanic Americans have long lagged the general population in terms of earning college degrees. Well, between 2010 and 2020, gains in the share of African Americans and Hispanic Americans with college degrees far outpaced those for the general population.

This has direct implications for unemployment. As this slide illustrates, high school graduates who don't attend college experience substantially higher unemployment rates than do workers with degrees. In September, for example, the unemployment rates were 2.1 and 4.1 percent, respectively, for degree holders and workers with only a high school diploma among people 25 and older.

Of course, caveats apply, but generally speaking, more workers with more education is good news on other fronts, too. A report from the New York Fed shows that the median wages of bachelor's degree holders exceeded those of high school graduates by more than 50 percent in 2022, a ratio that has changed little over at least the past three decades.

I don't mean to suggest that every person should attend college. There are certainly other pathways to better labor market outcomes, such as training and apprenticeships. In fact, the Atlanta Fed's Opportunity Occupations Monitor highlights many good jobs that one can attain through those routes. But college is a proven pathway that frequently leads to economic self-sufficiency and wealth building.

A word about the 2020 monetary policy framework

I focused the policy portion of this speech on the prepandemic era because that was when we learned about a changed interaction of unemployment and inflation, and accordingly shifted our understanding of what I call maximum sustained employment in important ways.

The 2020 framework codifies that our maximum employment mandate is inclusive. I think it's fair to interpret the underlying policy strategy as making sure we did not preemptively curtail the creation of jobs, in particular jobs most likely to help low- to moderate-income and minority communities.

Let me be clear on one other important point. The 2020 framework did not inform monetary policy during the economic crisis brought on by the COVID pandemic. The waves of sickness, snarled global supply chains, lockdowns, and other public health and fiscal measures associated with the pandemic triggered a surge of inflation that contrasted sharply with the low inflation environment contemplated by the "shortfalls" language of the framework. Like central banks around the world, the Fed had no choice but to decisively confront this heightened inflation to prevent an even longer and more debilitating period of intense price pressures; avoiding preemption of job creation was never a consideration.

Concrete steps to identify labor market barriers

I've talked at length about monetary policy. That's the well-known work of the Federal Reserve. You may not know that also in pursuit of sustained maximum employment, we spend considerable energy trying to identify barriers to full labor market participation and work with partners in the relevant fields to try to help reduce or eliminate them.

I'd like to highlight one particular program at our Bank.

Several years ago, a team of community development specialists and economists launched a research and advisory enterprise we call the Advancing Careers for Low-Income Families initiative. This program aims to provide information and data to workers, employers, and community and state leaders so workers can make better career decisions, employers can meet their talent needs, and leaders can help advance family economic mobility and resilience.

The initiative focuses on benefits cliffs that occur when a wage earner who receives multiple public benefits—SNAP, Medicaid, and so on—earns more income but comes out less well off because they exceed income eligibility thresholds for those benefits and thus lose access to them. Our team concluded that benefits cliffs constitute a punitive marginal tax on many of our fellow citizens who can least afford it. Basically, someone might earn an extra dollar, but lose $3 or $4 in public benefits.

Consequently, benefits cliffs become a perverse incentive for lower-wage earners to not gain new skills or try to climb a career ladder because, as our research shows, it typically takes a decade or more for the additional income to exceed the lost benefits. The people who are potentially affected totally get this—they are not dumb—and therefore they often forego training and a better job.

A key finding from our Advancing Careers team's work is that investing public resources to mitigate benefits cliffs—basically to tide people over by raising income thresholds, for instance—saves communities money in the long run. For one, over the long term, there is less outlay on public benefits as workers pursue career paths that allow them to stand on their own financially. The research also shows that tax collections rise. As more citizens earn family-supporting incomes, they pay income taxes and consume more goods and services.

Helping low-income Florida families

I'll share a quick story about the real-world value of this kind of objective research. And this story demonstrates that even in today's hyper-charged political environment, policies to mitigate benefits cliffs are achievable and, in some cases, uncontroversial.

This year, both chambers of the Florida legislature unanimously passed a law expanding eligibility standards for the state's publicly funded children's health insurance program, or CHIP. Starting January 1, 2024, families can earn up to 300 percent of federal poverty level income, up from the previous threshold of 200 percent, and qualify for the CHIP program.

Florida officials used analytical tools developed by our Advancing Careers team to clarify that the health insurance program was indeed creating benefits cliffs for many Florida workers. For some families, the 200 percent income cutoff meant that a modest wage increase could result in annual health insurance premiums soaring from around $240 to over $3,000.

Our Advancing Careers team figures the impending eligibility expansion can increase families' net financial resources as their earnings rise, and in the long run better position those families to build self-sufficiency and wealth.

Let me be explicit here and point out that we did not lobby for this policy shift—as I said earlier, the Fed does not do lobbying. Rather, our tool allowed policy makers to get objective information that informed their thinking about the issue and ultimately led them to pursue a policy change.

Policy moving forward

Let me conclude back where I began, with monetary policy.

In important ways, the pandemic emergency and inflation outbreak blew up the policy formulation that served to lengthen the prepandemic economic expansion, just as it upended the entire macroeconomy. Yet the understanding we absorbed in the final years of the prepandemic expansion remains with us and will continue to inform my policy thinking.

As for inflation, that is job one for now. As part of the work that undergirds the 2020 framework, we conducted numerous public events to gather input from a broad range of researchers, citizens, representatives of low- and moderate-income communities, employers, and elected officials.

A message that endures from those sessions was people want us to tackle inflation. Across the economy and demographic groups, inflation is the force that is most painful and drives more people to precariousness.

We heard clearly that two or three extra points of inflation, while it might save a tenth of a percentage point of unemployment, is a net loss for the populations on the wrong side of the wealth imbalance.

Looking ahead, after the COVID emergency fully passes, the world will have changed in ways we can't yet fully grasp. So, I cannot say with certainty that I will resume precisely the same modes of thinking about monetary policy that informed my views during the long expansion. What I can say is that the experience of those prepandemic years will inform tomorrow's mindset, as the Committee continues working to create an economic foundation that serves all Americans.

With that, I hope you have a better sense of how the Atlanta Fed and Federal Reserve System approach issues of economic disparities.

Even as these concerns rightly garner increased attention, in important respects a consensus around the best ways to address disparities remains elusive. That means researchers like you have a vital role to play in marshaling evidence so that policy is informed by sound information rather than stubborn misconceptions. I know my discussants today—all thought leaders on campus and beyond—have been active in this pursuit and have much to say.

Wealth inequality in our country has been well over a century in the making. It won't dissipate quickly. There is much to do, and much can go wrong. But I'm optimistic because we're having the right conversations, smart people are doing important research and practical work, and there is a real appetite for change.

I look forward to tackling these critical problems together.