Raphael Bostic

President and Chief Executive Officer

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

Money Marketeers of New York University Inc.

New York, New York

February 15, 2024

Key Points

- Atlanta Fed president and CEO Raphael Bostic says disinflation over the past year has proceeded without weakening of the labor market or economy, a stark departure from historical norms.

- Evidence suggests that previous monetary policy tightening cycles on average led to increases in the unemployment rate of 1.5 percentage points, Bostic notes. Today, after 11 federal funds rate increases, the unemployment rate has moved only from 3.6 to 3.7 percent.

- Bostic says he is grateful for substantial progress toward price stability, yet vigilant because the fight against inflation is not finished.

- Atlanta Fed business contacts are telling a story of expectant optimism that could unleash a burst of new demand that might reverse progress toward rebalancing supply and demand, Bostic notes. He says that scenario is a new upside risk to his outlook.

- He expects the rate of inflation will continue to decline, but more slowly than the pace implied by where the markets signal monetary policy should be.

Good evening. It's a pleasure to be back with the Money Marketeers.

The last time I was here was in November 2019. If only we had known what was looming four months from then, at which point all of our lives were turned upside down. I think our conversations that night would have been quite a bit different. I'm thankful that we've come a long way from the depths of the pandemic. I imagine you all are, too.

On that November evening, I talked about how the Atlanta Fed gathers and synthesizes data, survey findings, and anecdotal feedback to formulate a coherent monetary policy stance. These aspects of the policymaking process remain equally important today, though the macroeconomic context is quite different.

At that time, inflation had been below our 2 percent objective for the better part of a decade; most of us thought of global pandemics as historical oddities if we thought of them at all; and unemployment was continuing a steady decline that started soon after the Great Recession ended in 2009.

Fast forward to today. Combined with a healing supply side of the economy—including goods supply chains and labor supply—restrictive monetary policy has helped to decelerate the inflation rate more rapidly than even optimists expected. Yet inflation on a year-over-year basis remains above 2 percent. In a stark departure from historical norms, disinflation has proceeded absent significant weakening of the labor market or economic activity. That has been a most pleasant surprise.

This difference is stark and presents a challenge for me and my Fed colleagues. Today, I will try to offer some insights on how I'm approaching this challenge as I work to formulate a view of the appropriate path for monetary policy.

Now, I do not speak for the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) nor for the Federal Reserve Board. The thoughts I will share are strictly my own.

The economy, broadly speaking, is in a good position. But in good times and bad, monetary policymaking is a highly complex endeavor not fit for bumper-sticker solutions. That said, to communicate clearly to the public and markets, I like to identify certain key words that encapsulate my policy stance in the moment.

For the past two years, my watchwords have been purposeful, cautious, resolute, and patient: purposeful in formulating policy based not on noise but signals extracted from incoming data; cautious in calibrating my stance given broad uncertainty in the economy; resolute in my commitment to keep rates as high as needed to lower inflation to the Committee's price stability objective; and patient in my reaction to incoming data to be sure inflation is on a sustainable path toward 2 percent.

Conditions have changed, and so too have my watchwords. Today, my words are grateful yet vigilant: I am grateful for the substantial progress toward price stability. On a year-over-year basis, the headline inflation rate per the Committee's preferred gauge, the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index, is down to just over 2.5 percent from over 7 percent in mid-2022. Shorter-term measures are even more positive.

Yet I am vigilant because, despite clear progress in the fight against inflation with little damage to labor markets and the macroeconomy, the fight is not finished. Look no further than this week's Consumer Price Index (CPI) report for evidence of that. As Chair Jerome Powell pointed out in his press conference following the January FOMC meeting, the Committee will need to see continuing evidence to build confidence that inflation is moving down sustainably toward our goal.

Now you may have noticed that my descriptions of being patient and being vigilant were quite similar, and I concede the point. However, the context moves me to settle on a word that projects more timely urgency and care.

Let me say a bit more about the underpinnings of my vigilant posture.

Risks have become more balanced

Since responding to the 2021 spike in inflation by rapidly increasing the restrictiveness of monetary policy, the Committee has been seeking to manage two primary risks. One is staying in a highly restrictive stance for too long, thus potentially inflicting unnecessary damage to labor markets and the economy. The other is removing restriction too soon, which could leave the inflation rate stalled above 2 percent or spark a reacceleration that moves inflation further from our target. This latter scenario would conjure the unwelcome specter of the 1970s and '80s, when loosening policy too soon sparked repeated flareups in inflation that the Fed did not decisively quell for 15 years, and only then at the cost of two painful recessions.

While the second risk—that inflation doesn't get to target—has dominated my thinking since inflation spiked and we raised rates, today I see the risks as much more balanced. For example, absent some new shock to the economy, a reacceleration of inflation seems much less likely in the near and medium terms.

But let me share a truism I've come to appreciate profoundly: economic forecasting is difficult. If you have a friend you feel needs humbling, tell them to try it some time. (Certainly, none of us in this room needs to be told that.) While this truism holds generally, it is even more deeply true in an economy still seeking a path back to normal after the extreme disruption of everyday life associated with a global pandemic. Thus, one of the core messages of classic economics texts—aggressive rate hikes produce rising unemployment and slowing economic activity that suppress inflation—has not held up in our model-defying reality.

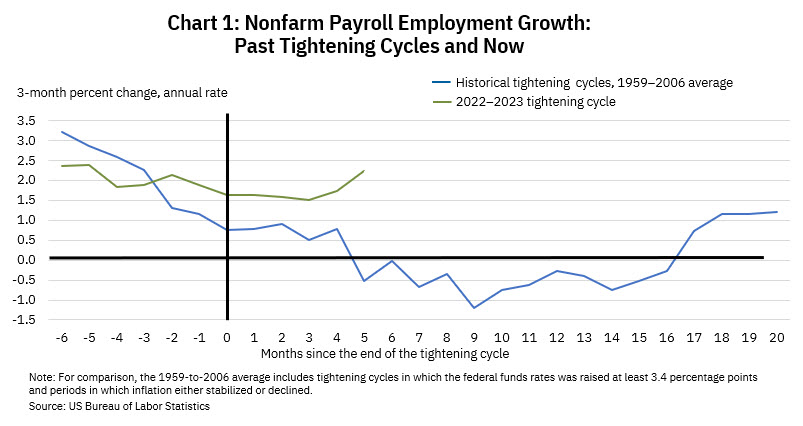

Instead, as inflation decelerated, employment growth has outpaced its performance amid previous tightening cycles (chart 1). The picture illustrates that monthly job growth slowed more dramatically in past cycles. In fact, employment growth turned negative on average within six months of the end of a tightening cycle. That has not happened this time. The disparity has actually widened between the strength of today's labor market and typical labor market conditions at this juncture in past tightening cycles.

Econometric evidence suggests that previous tightening cycles on average led to increases in the unemployment rate of 1.5 percentage points. Research from Christina and David Romer found that contractions in employment were most concentrated in the construction and durable goods manufacturing sectors.

Not this time. Those sectors have so far added employment. As for the entire labor market, when the Committee began raising the fed funds rate in March 2022, the headline unemployment rate was 3.6 percent; now, after 11 rate hikes, it's 3.7 percent.

Monthly payroll employment growth has been roughly a half percentage point stronger this cycle compared to historical norms, as the chart illustrates.

And after monthly employment growth slowed last fall, indicating a cooling labor market, job growth surged anew the past two months. Further, average hourly earnings picked up over the past three months. Wage growth will be a key metric to watch in coming months to determine whether these pressures are tied more to year-end salary adjustments or a signal of more persistent pressures from a tight labor market.

The labor market news is not all pointing in the same direction. Even as headline job growth and wage growth remain strong, another key labor market measure is signaling some cooling. The job openings rate peaked in March 2022 but has steadily declined since. Still, the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, or JOLTS, from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that the vacancy rate remains higher than it was at any point before the pandemic.

The upshot of all this: the labor market is remarkably strong considering tighter monetary policy and the steep decline in the rate of inflation.

As for GDP growth, the story is much the same. Econometric evidence suggests past tightening cycles on average led to about a half percentage point dip in real GDP over two to two-and-a-half years. By contrast, real GDP grew at a 3.3 percent annual rate in the fourth quarter by the initial estimate, and at a 3.1 percent clip for all of 2023. That's a more robust performance than private sector forecasts anticipated and, quite frankly, more robust than what we at the Atlanta Fed expected.

It is more than the aggregate data suggesting the economy and labor market may still have gas in the tank. As I discussed in my earlier visit with you, our Bank employs a team that gathers and analyzes anecdotal reports from business contacts across the Southeast.

Today, the gist of the story we hear from contacts is that, despite moderating activity, businesses are not distressed. Rather, many are sitting on pause, awaiting the optimal time to deploy assets and resume hiring to expand their operations. To me, this carries the ring of expectant optimism—perhaps even pent-up exuberance—with the potential to unleash a burst of new demand that could reverse the progress we have observed toward rebalancing supply and demand across the economy. In my view, this constitutes a new upside risk to my outlook that bears scrutiny in coming months.

That's anecdotal evidence, yes. But I trust our grassroots intelligence as an essential complement to the data. Our methods of gathering and processing feedback are sound, and the information from our Regional Economic Information Network has proven prescient before. To cite one instance, our contacts sounded early warnings in 2021 that emergent price pressures were likely to persist beyond just a few months.

That feedback was one reason why, if I may say so, I was a relatively early skeptic concerning the transitory inflation narrative.

So, scanning the broad macroeconomic horizon, one can only conclude that this monetary policy cycle is different. And just like you all as market participants, I as a monetary policymaker must grapple with new realities and formulate policy positions at a time when our go-to templates are of limited utility.

We are not done with inflation

What I am gleaning from those new realities right now is that a durable labor market rally, alongside muscular economic growth and resurgent business optimism, would argue for continued patience in unwinding monetary policy restriction.

But what of declining inflation? Well, on the surface, rapid deceleration would appear to offer a counterargument to leaving restriction in place much longer. As I noted, headline numbers on a 12-month, six-month, and three-month basis are at or near the Committee's 2 percent objective. Though the upside surprise in the January CPI will probably translate, at least partially, into a higher PCE inflation report, these trends will not likely be substantially reversed as a result of one month's data. But even if that is not the case, I require more confidence before declaring victory in this fight for price stability. Allow me to dig a little deeper and explain why.

First, goods inflation may rebound a bit in coming months (chart 2). Many businesses still have inventories to work through, and may ramp up orders for goods once those inventories are exhausted. As the chart illustrates, falling goods prices have accounted for a significant share of the decline in the inflation rate, so a reversal there could complicate the pursuit of price stability.

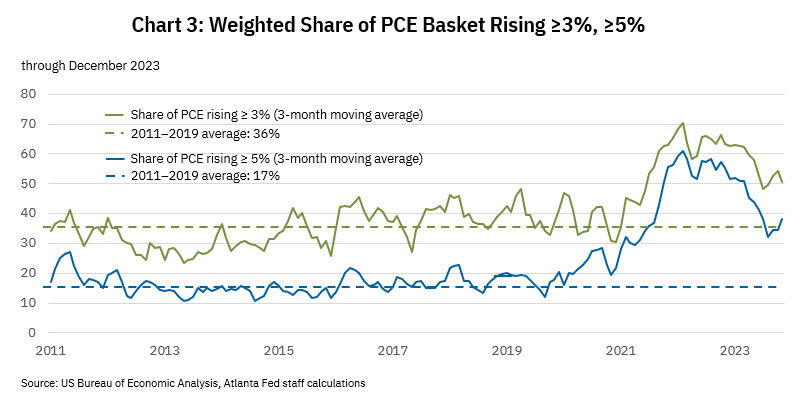

Second, a shade over a third of the PCE basket rose at rates at or above 5 percent in December (chart 3). That share is in line with similarly elevated reports over the past six months and remains well above the roughly 20 percent share that would be consistent with a price change distribution when inflation is at its target, as the slide shows. So, inflation pressures are still more broad-based than we'd prefer, frankly.

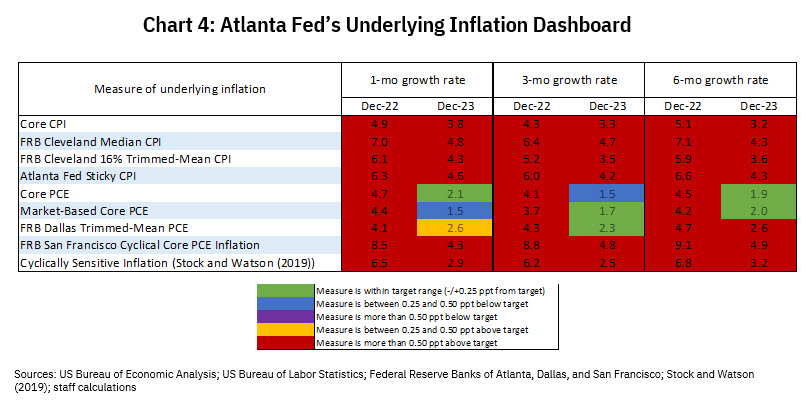

The third piece of evidence I'll cite in arguing that it is not yet time to be sanguine about inflation is that the Dallas Fed's trimmed-mean PCE price statistic, which is one of the better predictors of the near-term inflation trend, posted a 2.6 percent annualized increase in December, identical to its reading over the past six months. That suggests that underlying inflation is still loitering just outside the neighborhood of 2 percent.

Finally, note all the red in this picture (chart 4). This is our Underlying Inflation Dashboard. Red means, basically, well above target, and as of December, two-thirds of the metrics that comprise the dashboard are still in the red.

Beyond nuts-and-bolts inflation dynamics, the world at large remains rife with uncertainty that could still derail our progress to price stability. Consumer debt loads are growing, particularly among those at the lower end of the income and wealth distribution. Geopolitical risks could rattle energy markets or financial markets and reintroduce snarls in supply chains, developments that would likely exert upward pressure on prices.

History may not be a good guide

Finally, let me plainly state a reality that I think is quite important: economic history does not seem to be repeating itself. While this will be something that economic historians will ultimately debate over coming years, my staff and I have been wrestling with what we think might be two reasons for this.

For one, we are still navigating the turbulent wake of what we hope was a once-in-a-century global pandemic. Few models contemplated severe kinks in global supply chains resulting from clogged seaports and factory closures; months when tens of millions of consumers would be homebound while retail stores, entertainment venues, and the travel industry were paralyzed; governments providing trillions of dollars in fiscal support; and the US labor market abruptly losing 20 million jobs.

If there is an overarching lesson I've taken from the pandemic experience, it is humility: to expect to be surprised. If we use that admittedly simple intellectual framing, then the atypical macroeconomic effects of this aggressive monetary policy tightening regime should perhaps be less surprising.

Second, a case can be made that the US economy has grown less sensitive to interest rates. That's in part because the most interest-sensitive sectors, concentrated in goods production, account for a dwindling share of overall economic activity. In a 2018 paper, Jason Brown of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City calculated that over the past 50 years, the share of GDP from services has risen from nearly 60 percent to 80 percent, while the goods production share shrunk by half.

On top of the role played by compositional industry shifts, research by Atlanta Fed economist Jon Willis found that the transmission of monetary policy to individual industries has weakened over time. Using the response of employment to changes in the federal funds rate as the measure of monetary policy transmission, the analysis suggests that the interest sensitivity of employment has declined since the mid-1980s for nearly all industries as well as for the overall economy.

If rate sensitivity has declined, the implications for policy are potentially significant. For example, the efficacy of monetary policy could generally be lower or those making monetary policy might need to hold rates at either a restrictive or stimulative posture for longer to generate the same economic response. These would be big deals.

But let me acknowledge another thing: this is not settled economics. Even within my building, there is a debate about how enduring these changes will be in the longer term. In my view, this will be something that economists will be debating for many years to come.

But even if you don't buy arguments for structural change, it remains true today that many households and businesses have refinanced into low-cost loans that have locked them into payments streams that will not be as sensitive to interest rates as they might be in more normal times. That, plus the extra cash that many have on hand, might mean less sensitivity to our policy moves in the shorter term.

So to close, looking ahead, my expectation is that the rate of inflation will continue to decline, but more slowly than the pace implied by where the markets signal monetary policy should be. As some colleagues and I have noted, we will likely soon contemplate the appropriate time for monetary policy to become less restrictive. Right now, a strong labor market and macroeconomy offer the chance to execute these policy decisions without oppressive urgency.

Put simply, we have made substantial and gratifying progress in slowing the pace of inflation. All things considered, the US economy is in a good spot, even an enviable spot compared to other major economies.

But from my vantage point, the evidence from data, our surveys, and our outreach says that victory is not clearly in hand, and leaves me not yet comfortable that inflation is inexorably declining to our 2 percent objective. That may be true for some time, even if the January CPI report turns out to be an aberration. So that gratitude will be accompanied by vigilance, and I will be ready to do what it takes to achieve our monetary policy mandates.

Thank you, and I'd be happy to take some of your questions.