By Raphael Bostic, President and Chief Executive Officer

By Raphael Bostic, President and Chief Executive Officer

November 29, 2023

The central lesson I took from the pandemic years was this: expect to be surprised.

Even today, economic signals remain mixed. In recent months, there's been a disagreement between incoming aggregate data and feedback we at the Atlanta Fed are gathering through our surveys and on-the-ground outreach. In fact, one of our economists calls the current economic picture a Rorschach test of conflicting signals—you may see a dragon, someone else sees a butterfly.

Nevertheless, I'm sensing greater clarity about a few important currents. One is the direction of inflation. There's no question the rate of inflation has slowed materially over the past year-plus, and thus far we have avoided a disruptive surge in unemployment that often accompanies a steep slowdown in price increases.

Just as important to my monetary policy thinking, our research and input from business leaders tell me the downward trajectory of inflation will likely continue. Thirdly—and one of the reasons I think inflation will keep falling—our intelligence leads me to believe economic activity will slow in the coming months, in part because restrictive monetary policy and tighter financial conditions are creating greater restraint on economic activity.

So, that's the butterfly I see.

On the other hand, recent incoming data—on gross domestic product growth, consumer spending, business investment, job creation—tell us economic activity has remained surprisingly resilient in the face of tighter monetary policy. So resilient, in fact, that it might appear to some that growth could continue to plow ahead above the long-term trend level. That is not the usual recipe for lower inflation. Given this ink blot of an economic outlook, why am I seeing mostly a butterfly for monetary policy making?

Let me first recap the trajectory of inflation.

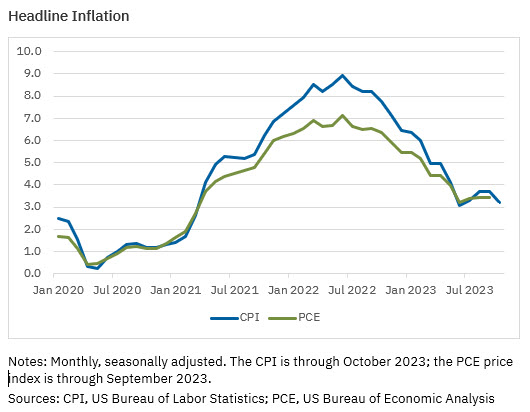

Over the past 15 months, though prices have continued upward, the pace of that climb has slowed considerably. On average, prices are rising about half as fast as they were in the summer of 2022, according to the two most prominent inflation gauges, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index (see the chart).

That said, inflation remains above 3 percent. Our objective is 2 percent, as measured by the PCE price index, so we still have a ways to go. As I've emphasized, the path to 2 percent will be bumpy, as evidenced by the fluctuating monthly inflation prints in recent months. But we'll get there.

Why do I think inflation will keep falling?

In explaining my case for continued disinflation, I'll start with the feedback my staff and I are gathering. In recent weeks, the core story contacts are telling our Regional Economic Information Network (REIN) staff has not changed. Rather, it has solidified. Evidence has continued to accumulate suggesting that tighter monetary policy is biting harder into economic activity.

From farmers delaying purchases of high-tech tractors to home builders offering incentives to lure buyers leery of rising mortgage rates, tighter financial conditions appear to be restraining activity more and more.

Relatedly, my staff and I are picking up clear signals that companies' pricing power is diminishing. That is, it is no longer easy to raise prices without resistance from customers. In that context, we're hearing reports of more and more companies sacrificing some profit margin to maintain market share. Firms are increasingly offering discounts and price promotions or otherwise swallowing cost increases rather than risk chasing away customers.

To be sure, reduced pricing power is not brand new for goods producers and sellers. The fresh information here is that pricing power is also eroding for providers of business and consumer services. That's significant because price increases have been far more persistent for services than for goods.

In the main, wage growth is also slowing. While there are differences among industries and, especially, locations, many firms across the Southeast tell our field staff they are reverting to annual pay raises of 2 to 3 percent on average, down from 3 to 5 percent and occasionally higher during the past three years. Wages are the biggest cost for many firms, especially those in service sectors.

Taken together, the feedback from business contacts points to ongoing disinflation and a measured slowing in economic activity. The good news is that, in the view of most of our contacts, activity is decelerating but not dramatically enough to portend a destructive economic downturn.

Surveys back up anecdotal evidence

Survey results support the anecdotal feedback our staff gathered. In the October Survey of Business Uncertainty (SBU), respondent firms on average forecast their sales to increase about 3 percent over the next year. That's the lowest reading the SBU has recorded since its inception nearly a decade ago other than during the worst of the pandemic.

On the consumer side, there are a few reasons why spending could slow from the lofty levels that have buoyed economic activity in recent quarters. We have already noted that wage growth is likely to slow. Further, though the picture on pandemic-era savings is not entirely clear, it appears this stockpile is dwindling but may keep fueling consumption into next year, according to research from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. And the end of relief programs such as childcare subsidies and student loan forbearance could further weaken consumer spending in coming months.

Consumer spending accounts for roughly two-thirds of GDP, so less shopping will mean slower economic growth. Our research staff forecasts growth around 2 percent for the fourth quarter and just above 1 percent for next year. The staff projects unemployment to nudge up from 3.9 in October to 4 percent and hold there as labor markets continue to loosen.

When economic growth throttles back, that typically is associated with a slowdown in inflation.

Our latest surveys of business decision makers suggest as much. The October Business Inflation Expectations (BIE) survey finds that, on average, firms expect to increase prices 3.4 percent over the next 12 months. That's the lowest 12-month-ahead projection in the monthly survey since early in this inflationary episode (July 2021), and less than half the average firm's price hike over the previous 12 months—7.8 percent.

The median BIE survey respondent also plans to change the price of their main product or service just once in the next 12 months, versus twice in the past year. Our inflation experts label this shift in pricing plans a return to a "time-dependent" approach, meaning companies adjust prices according to a set schedule. That's fundamentally different from the "state-dependent" approach that prevailed the past couple of years, as firms increased prices frequently in response to rapidly rising costs.

After synthesizing all the data and anecdotal input, our staff forecasts inflation to decelerate to 2.5 percent by the end of 2024 and closer to 2 percent by the end of 2025.

Altogether, the research, data, survey results, and input from business contacts tell me that tighter monetary policy and tighter financial conditions more broadly are biting harder into economic activity. At the same time, I don't think we've seen the full effects of restrictive policy, another reason I think we'll see further cooling of economic activity and inflation.

Admittedly, the case for economic slowing ahead may seem hard to square with the indicators I mentioned above—healthy growth in jobs, consumption, and business investment, to name three—and with GDP growth of 4.9 percent in the third quarter, per the initial estimate from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. But based on the totality of the evidence I've presented, I simply don't think that kind of blockbuster expansion is durable given the current restrictive stance of monetary policy in combination with tight financial conditions.

And while I always view economic projections with a healthy degree of caution—especially in these times of heightened uncertainty—I believe we can feel more confident in the outlook just now. One reason is that the surveys I cited—the Atlanta Fed's BIE and SBU as well as our estimating tool, GDPNow—have been reliable lately. And the anecdotal feedback we gather from business leaders has likewise proven dependable.

The accuracy of GDPNow, in fact, has improved significantly in 2023. In the first three quarters, GDPNow's final estimates missed the actual gross domestic product growth number by an average of just 0.2 percentage points. The average miss for each quarter of 2020 through 2022 was 1.6 points.

Declining inflation doesn't mean declining prices

Before I conclude, I want to clarify that a declining inflation rate does not mean prices actually fall. What we are experiencing is called disinflation. When prices on average decline, that's deflation.

Deflation might sound appealing. After all, who wouldn't want to pay less for groceries next week? But it can be economically destructive. Consumers may delay purchases because they expect prices will keep falling. That can curtail overall consumption, which can prompt businesses to cut production, which in turn can mean lower profits, cost cutting, and layoffs.

I've written mostly about inflation here. But the Fed has a dual mandate from Congress to pursue not only price stability but also maximum employment. Our policy-setting Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) selected a target of 2 percent inflation as both a stable rate of price growth that allows households and businesses to plan effectively and a level most consistent with maximum employment.

It's important to remember that calibrating monetary policy involves striking a balance: an economy that produces healthy employment growth without stoking high inflation. In the judgment of the FOMC, a key characteristic of that economic sweet spot is an inflation rate averaging 2 percent over time.

That is what my fellow FOMC participants and I are working daily to achieve. And we will not rest until inflation is decisively bound for our objective.