Hurricanes, a massive oil spill, and a terrorist attack are among the catastrophes that tested the resilience of the Southeast and the Atlanta Fed in the past quarter century. In virtually every case, the Reserve Bank passed those tests resoundingly.

At least a dozen hurricanes struck the Southeast over those years, including eight between 2004 and 2005, the most massive of which was Hurricane Katrina (see video below). The largest oil spill in the nation's history contaminated the Gulf of Mexico and damaged Gulf Coast economies in 2010. And, of course, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, traumatized the region along with the rest of the nation.

Hurricanes took a toll

Hurricane Andrew, the second costliest storm in U.S. history, after Hurricane Katrina, struck south Florida in August 1992. It destroyed more than 150,000 homes and disrupted power to more than a million people. However, at the Atlanta Fed's Miami Branch, a dedicated staff—some sheltered at the branch with their families—worked under generator power to distribute high volumes of cash to meet the increased local demand.

Holding the Fort during and after the Storm

For 13 days and nights, Mike Fieramusca ate military-style "meals ready to eat" (MREs), drank and bathed in water siphoned from a 20,000-gallon reserve tank, and, as the situation called for, slept on cots in the boiler room of the Atlanta Fed's New Orleans Branch. "It's my job to stay here and make sure this building survives whatever is thrown at it," said Fieramusca, the New Orleans building superintendent. "If we don't have this building, folks don't have a place to work."

The deteriorating conditions outside created a demanding test of patience and resourcefulness inside the branch. As the temperature climbed above 95 degrees, Fieramusca and two Federal Reserve law enforcement officers fashioned standard-issue post-Katrina survival uniforms—T-shirts, shorts, and bulletproof vests. Carrying a fire extinguisher, Fieramusca moved constantly about the property to check on essential functions. A persistent worry was flaming ash from a nearby fire that rained down on the building's rooftop.

As a small and determined group held on, Senior Financial Services Project Leader Jude Miller rushed to bring in relief. Starting from his native southwestern Louisiana, Miller began his own epic journey, driving his truck east across low-lying back roads. Using his personal radio equipment to stay in touch with Fed management in Atlanta and Birmingham, Miller made frequent stops in the countryside to purchase fuel and other supplies for the branch, at several points negotiating for purchases in Cajun French.

At Baton Rouge, Miller joined a group of Federal Reserve protection officers who had driven from Atlanta, and from there he led the group along the treacherous route to New Orleans. The convoy passed many miles of traffic by riding on the shoulder, making its way along roads jammed with heavily armed and upset civilians and past military checkpoints. U.S. Army soldiers waved the convoy through after Miller turned on flashing blue lights on his truck and showed federal homeland security authorization papers—official documents provided by the Fed Board of Governors in Washington.

Finally, Miller and his convoy reached the branch, and Fieramusca opened the gate to let the group with the much-needed fuel, water, food, clothing, toothbrushes, and other supplies—and, above all, manpower—into the parking lot. The building was secure for the remainder of the emergency period.

Nine years after Andrew, the 2001 terrorist attacks also disrupted the Atlanta Fed's operations. After the attacks, the broader Fed System and the Atlanta Fed played critical roles in keeping the nation's financial system intact, thus preserving public confidence in that crucial component of our nation's economy. For the Atlanta Fed, the attacks spurred renewed focus on contingency planning, which would prove highly beneficial amid the storms to come.

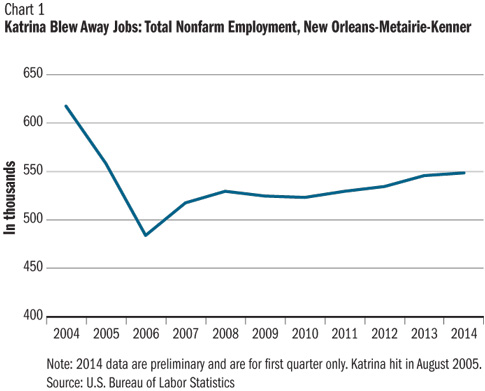

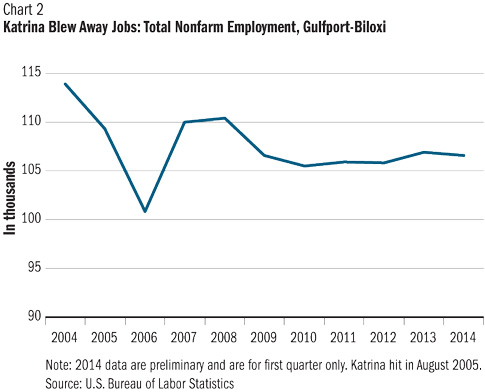

For as difficult as 9/11 was, in a practical sense Hurricane Katrina tested the mettle of the Atlanta Fed and its people, especially those in New Orleans, like no other disaster. Many of the 179 employees at the Reserve Bank's New Orleans Branch lost their homes to flooding after the hurricane struck on August 29, 2005. It took two weeks to account for all of the New Orleans staff, and none was lost. The branch office was closed for operations for nearly a month, but a stalwart crew stayed on site to secure the vault and property (see "Holding the Fort during and after the Storm").

"The mental and emotional damage was absolutely incredible," said Robert Musso, who was then head of the Atlanta Fed's New Orleans Branch. Katrina and its resulting flooding left more than 1,500 dead, mainly in Louisiana and Mississippi. Property damage exceeded $100 billion. Katrina was "the single most catastrophic natural disaster in U.S. history," according to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

With infrastructure crippled, cash was king

The Atlanta Fed helped devastated communities of the Gulf Coast reclaim a semblance of normalcy following the storm. As many areas in Louisiana and Mississippi lacked power for several weeks, 21st-century commerce ceased. Thousands of people had no access to automated teller machines or credit and debit card transactions. Cash, therefore, was king (view video above). Commercial banks badly needed currency to meet heightened customer demand. The Atlanta Fed's New Orleans Branch would normally supply the cash, but it was closed. Making matters worse, many of the commercial bank buildings in south Mississippi and Louisiana were flooded, making it difficult in some cases to know where to deliver currency.

Under these trying circumstances, Atlanta Fed officials in New Orleans and Atlanta quickly instituted contingency plans. The Reserve Bank stationed its New Orleans cash department leaders in Birmingham to coordinate innovative methods to supply cash to storm-ravaged areas. They called on Fed offices in Atlanta, Birmingham, Jacksonville, and Houston to provide cash (watch former First Vice President Pat Barron video above). Leaving their homes for weeks, New Orleans staff also partnered with a few large commercial banks in key Gulf Coast markets to deliver them cash, then those institutions assisted in distributing cash to smaller banks nearby.

The aftermath of Hurricane Katrina was a wrenching but ultimately proud chapter in the history of the Atlanta Fed.