Trade worries remain at the forefront of economic news. Average tariffs on Chinese imports now stand at 21 percent, up from 3 percent in March 2018. Earlier this month, President Trump suspended plans for further tariff hikes on Chinese goods. Also this month, the U.S. is rolling out new tariffs on $7.5 billion worth of imports from Europe. On another front, fears are growing that Congress may not approve the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Trade Agreement, the intended successor to the North American Free Trade Agreement. Data from the folks at policyuncertainty.com say that articles about trade policy uncertainty in U.S. newspapers were more than 10 times as numerous in the third quarter of 2019 as the average from 1985 to 2010.

Trade policy worries extend beyond the newswires. We hear concerns about trade policy in reports from Main Street firms in the Sixth District collected through our Regional Economic Information Network and, more broadly, in the Federal Reserve's Beige Book. Amid reports of softening manufacturing conditions in the U.S., slowing growth in payroll employment, and a drop-off in business investment, it's natural to wonder whether trade policy is at least partly to blame. Professional forecasters seem to think so. For instance, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts that the U.S.-China trade dispute will shave roughly three-fourths of a percent from global output by 2020, which, as the IMF's managing director noted, is "equivalent to the whole economy of Switzerland."

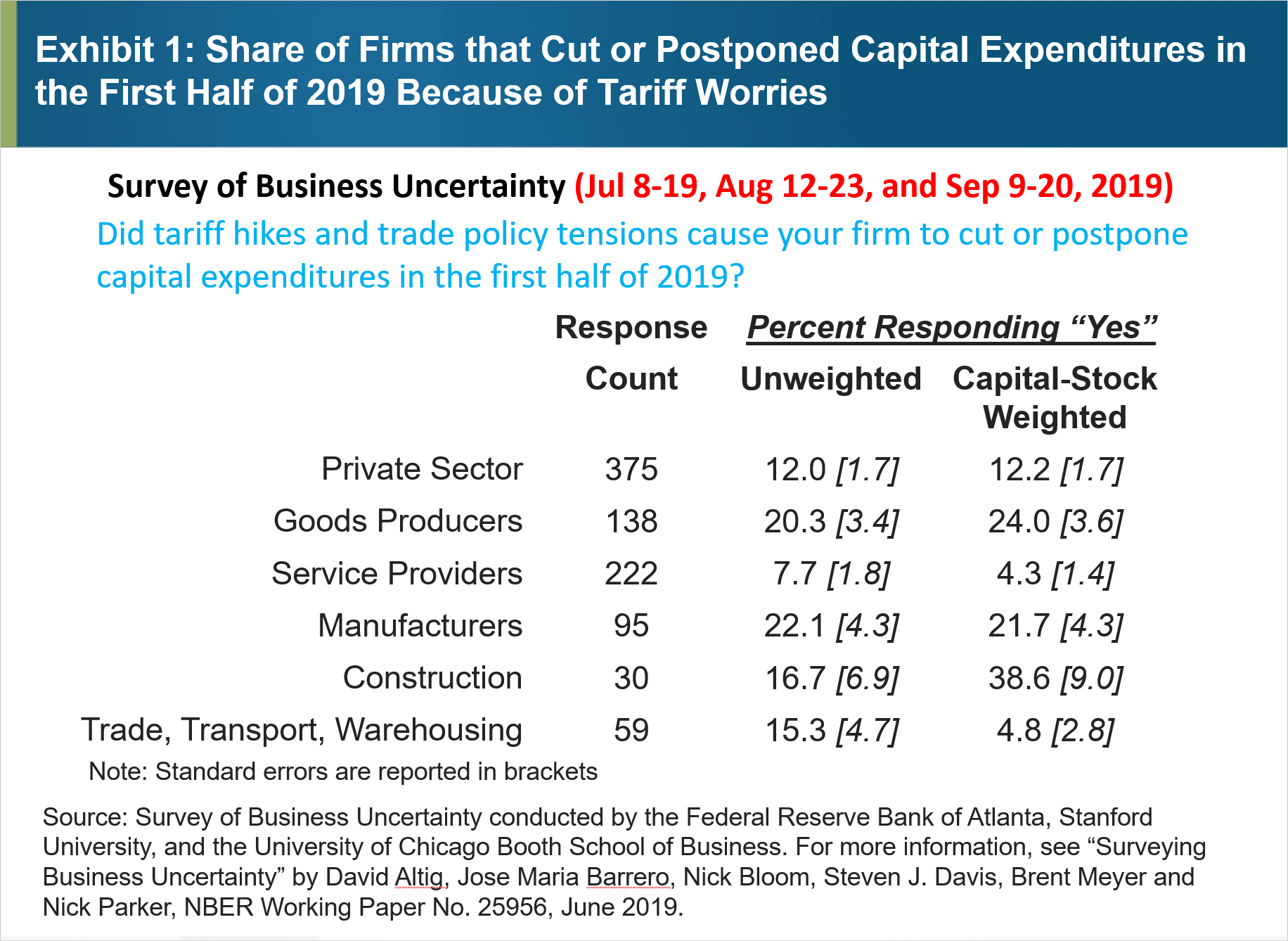

Over the past year and a half, we have been keenly interested in how trade policy worries affect business decision making. In August 2018, we reported that trade concerns prompted about 1 in 5 firms to re-evaluate their capital investment decisions. At the same time, only 6 percent of the firms in our sample had then decided to cut or defer previously planned capital expenditures in response to trade policy developments. Early this year, we noted that the hit to aggregate investment from trade tensions and tariff worries was modest in 2018, but firms believed the impact would increase in 2019.

As U.S.-China trade tensions escalated during the third quarter of this year, we went back into the field, posing another set of trade-related questions to panelists in our Survey of Business Uncertainty (SBU). This time around, we asked both backward- and forward-looking questions about the perceived effects of trade policy, and we expanded the scope of our questions to cover employment and sales in addition to capital expenditures.

Overall, our results say that the negative effects of trade policy developments on U.S. business activity have grown over time, particularly for firms with an international reach. Trade policy effects on the business sector as a whole remain modest but larger than we saw six or 12 months ago.

Twelve percent of surveyed firms reported cutting or postponing capital expenditures in the first six months of 2019 because of trade tensions and tariff worries (see exhibit 1). That's twice the share when we asked the same question a year earlier. Given the capital-intensive nature of manufacturing, it is perhaps more concerning that one in five manufacturing firms now report cutting or postponing capital expenditures because of trade policy tensions.

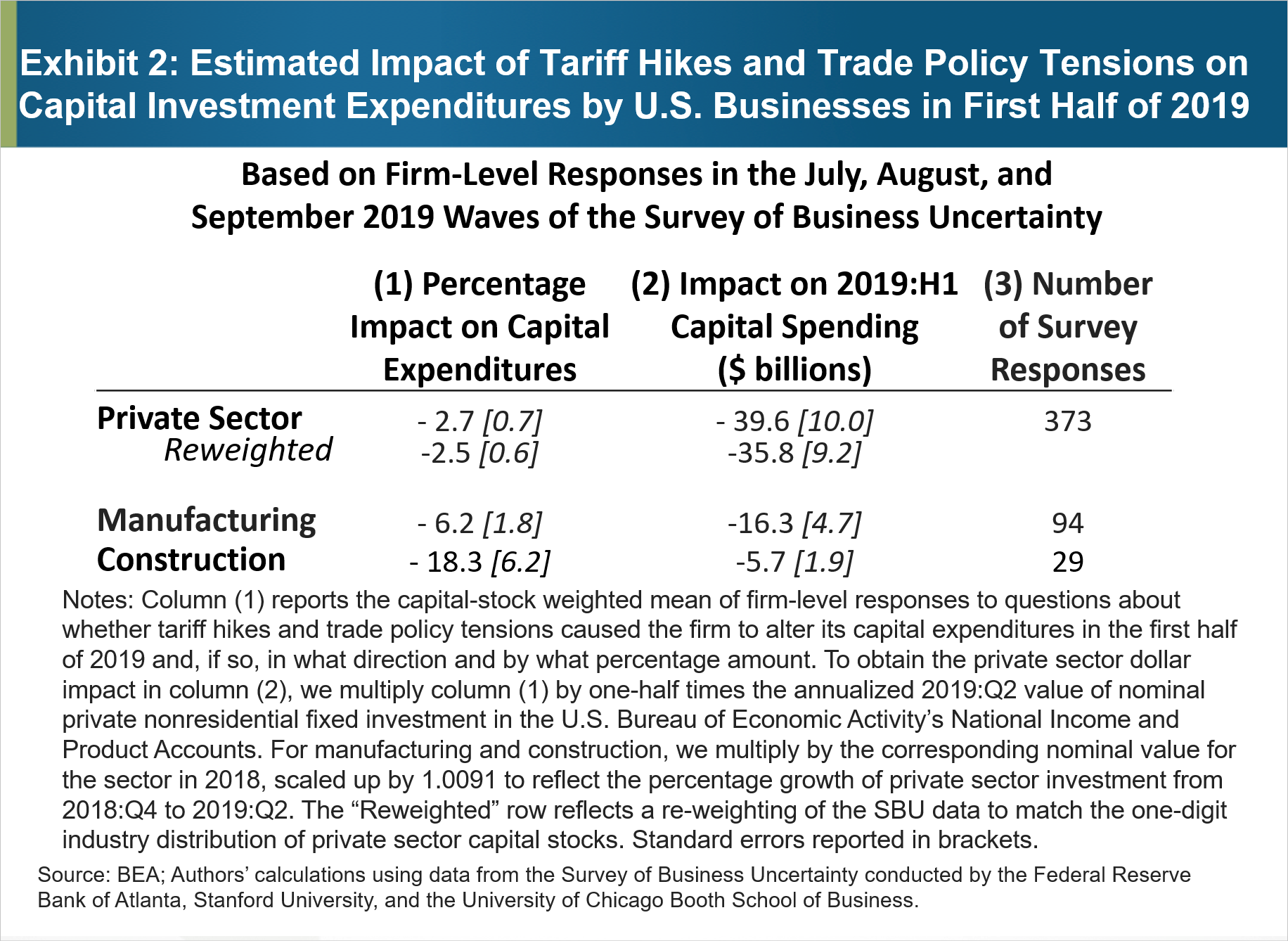

We also find that tariff hikes and trade policy tensions now exert a larger negative impact on gross U.S. business investment. Exhibit 2 uses SBU data on whether firms changed their capital expenditures due to trade policy tensions and, if so, by how much and in which direction. Column (1) reports the average percentage impact in the sample, where we weight each firm's response by its capital stock value. To estimate the dollar impact of trade policy developments in column (2), we multiply the weighted-average percent change by actual U.S. business investment in the first half of 2019, which yields an estimated effect on U.S. business investment of about minus $40 billion.

This estimated trade policy hit to aggregate investment is modest but roughly double what we previously found for the second half of 2018. Our results say that investment is hardest hit in manufacturing and construction, though perhaps for different reasons. The larger response for manufacturing is likely due to its higher international exposure, both in direct goods trade and across the supply chain. For construction, the impact is likely due to an increased cost of imported materials and equipment.

Exhibit 3 reports the estimated effects of tariff hikes and trade policy tensions on private sector employment and sales in the first half of 2019. According to our results (reached by using the same procedure as in Exhibit 2), these developments subtracted about 40,000 jobs per month from nonfarm payrolls and about $259 billion in sales over the first half of the year. Though this employment impact is sizable, it is not estimated very precisely (one standard error corresponds to about 24,000 jobs per month). The estimates for the impact of tariff hikes and trade policy tensions imply about $1.1 million* in lost sales per lost job.

Notes on Exhibit 3: In Panel A, column (1) reports the employment-weighted mean response to questions about whether tariff hikes and trade policy tensions caused the firm to alter its employment level in the first half of 2019 and, if so, by what percentage amount. We deleted three questionable responses to the employment question that we could not verify. To obtain the aggregate employment impact in column (2), we multiplied the column (1) value by the average nonfarm private sector payroll employment in the first half of 2019. The "Reweighted" row reflects a re-weighting of the SBU data to match the one-digit industry distribution of private sector payroll employment. In Panel B, column (1) reports the sales-weighted mean response to questions about whether tariff hikes and trade policy tensions affected the firm's sales in the first half of 2019 and, if so, by what percentage amount. To obtain the aggregate sales impact in column (2), we multiplied the column (1) value by Nominal Gross Output: Private Industries. According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, gross output is, "principally, a measure of an industry's sales or receipts. These statistics capture an industry's sales to consumers and other final users (found in GDP), as well as sales to other industries (intermediate inputs not counted in GDP). They reflect the full value of the supply chain by including the business-to-business spending necessary to produce goods and services and deliver them to final consumers." The "Reweighted" row reflects a re-weighting of the SBU data to match the one-digit industry distribution of private sector gross output. Standard errors are reported in brackets.

We also asked forward-looking questions to assess whether firms think trade policy worries will continue to dampen their business activities in the second half of 2019. Exhibit 4 summarizes our findings in this regard. SBU respondents anticipate that the impact of trade policy on their second-half sales revenue will be similar to what they reported for the first half of 2019, but they anticipate somewhat larger negative effects on their capital expenditures and employment. Across the private sector as a whole, SBU respondents see their capital expenditures as down by 3.8 percent in the second half of 2019 due to tariff hikes and trade policy tensions.

In sum, as trade policy tensions escalated in the first half of 2019, our results say that businesses took a hit to their sales and backed off on hiring and investment. Moreover, firms anticipate that the negative effects will continue during the second half of 2019. Our estimated impact magnitudes are rising over time but remain modest.

We should also note that our estimates do not capture certain effects. For instance, they don't capture the pass-through of tariff hikes to American consumers in the form of higher prices or to American companies in the form of compressed margins and lower profits. Tariff hikes and trade policy tensions also slow growth in the global economy, with negative effects on the U.S. economy. These blowback effects are also outside the scope of our investigation.

*When this post was originally published, the figure was $110,000 due to an error in the calculation.

By

By  Jose Maria Barrero, assistant professor of finance at Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México Business School,

Jose Maria Barrero, assistant professor of finance at Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México Business School, Nick Bloom, the William D. Eberle Professor of Economics at Stanford University,

Nick Bloom, the William D. Eberle Professor of Economics at Stanford University, Steven J. Davis, the William H. Abbott Professor of International Business and Economics at the Chicago Booth School of Business and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution,

Steven J. Davis, the William H. Abbott Professor of International Business and Economics at the Chicago Booth School of Business and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution,

Nick Parker, the Atlanta Fed's director of surveys

Nick Parker, the Atlanta Fed's director of surveys