Here's a puzzle. Unemployment is at a historically low level, yet nominal wage growth is not even back to prerecession levels (see, for example, the Atlanta Fed's own Wage Growth Tracker). Why is wage growth not higher if the labor market is so tight? A recent article in the Wall Street Journal posited that the low rate of job-market churn likely explains slow wage growth. Switching jobs is typically lucrative because it tends to be going to a job that better uses the person's skills and hence offers higher pay. Job switchers can also help improve the bargaining position of job-stayers by inducing employers to pay more to retain them.

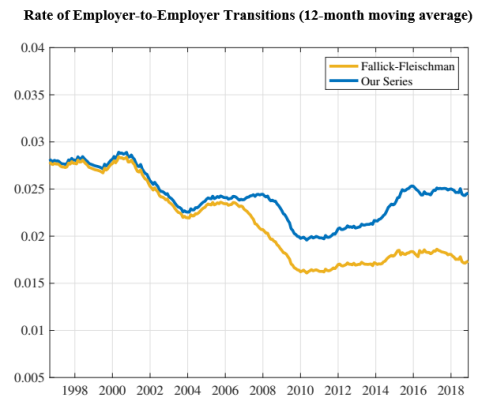

But is the job-switching rate really lower? A paper that Shigeru Fujita, Guiseppe Moscarini, and Fabien Postel-Vinay presented at the Atlanta Fed's 10th annual employment conference looked at a commonly used measure of employer-to-employer transitions. That measure, developed by Fed economists Bruce Fallick and Charles Fleischman in 2004, uses data from the Current Population Survey (CPS) on whether a person says that he or she has the same employer this month as last month. Job switchers are those reporting having a different employer. As the following chart shows, the Fallick and Fleischman data (the yellow line) support the Wall Street Journal story that the rate of job switching is much lower than it used to be.

Source Fujita et al. (2019)

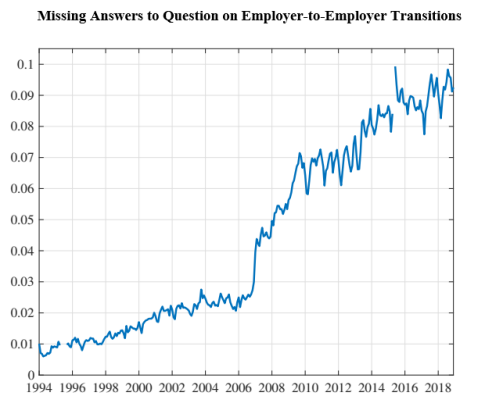

However, Fujita and his coauthors discovered a potential problem with these data, noting that the CPS doesn't ask the same-employer question of all surveyed people who were employed in the prior month. Importantly, the incidence of missing answers has increased dramatically since the 2006, as the following chart shows.

Source Fujita et al. (2019)

If these missing answers were merely randomly distributed among job switchers and job stayers, then it wouldn't matter much for the Fallick-Fleischman measure. But Fujita et al. found that the missing answers were disproportionately from people who look more like job switchers in terms of observable characteristics such as age, marital status, education, industry, and occupation—making it likely that the Fallick-Fleischman measure undercounts job switchers.

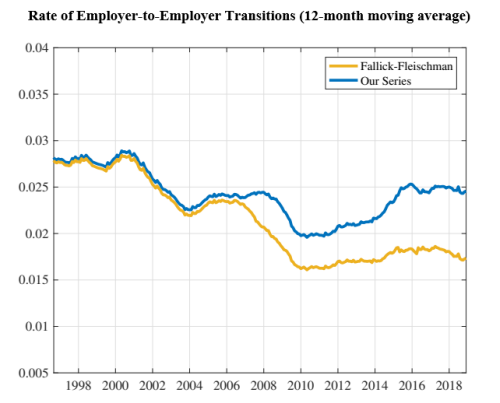

The researchers developed a statistical adjustment to the Fallick-Fleischman measure to account for this bias (the blue line label our series in the following chart—this is the same as the first chart) that tells a somewhat different story than the original measure (yellow line).

Source Fujita et al. (2019)

In particular, the adjusted job-switching rate is only moderately lower than it was 20 years ago and has fully recovered from the decline experienced during the Great Recession. Although a decline in job switching might be a factor in the story behind low wage growth, based on this adjusted measure it doesn't seem like the dominant factor. The low wage growth puzzle remains a puzzle.

By

By