In this report, we provide details of the analysis presented in the accompanying macroblog post to demonstrate how the assistance offered in The Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCR Act), signed into law on March 18, and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act), signed into law on March 27, supplement the pre-existing social safety net to financially support American workers displaced because of the COVID-19 pandemic. (In addition, the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act was signed into law on March 6 and provided $8.3 billion in emergency funds to state and local governments to fight the outbreak.)

We use as an example a hypothetical single adult with no children who was working at a restaurant and making under $75,000 a year (the threshold for receiving maximum assistance under the acts). Around 45 percent of workers earn less than $75,000 a year, according to the monthly Current Population Survey and our calculations. We assume the restaurant is forced to close and lay off the worker because of COVID-19 restrictions, and we then calculate the financial assistance he can expect to receive under the acts when he becomes unemployed. For comparison, we also calculate the amount he would have received under the preexisting policy to show the net impact of the FFCR and CARES acts.

To what extent the FFCR and CARES acts helps stabilize a worker also depends on state-specific social safety net policies as well as regional differences in wages and cost of living. We compare how the hypothetical worker would fare in two cities with different state social safety nets, wages, and living costs: Boston, Massachusetts, and Birmingham, Alabama. Massachusetts social safety net laws, including unemployment insurance and health insurance, provide more financial assistance than Alabama social safety net laws. However, while the social safety net provides more in financial resources, the cost of living is higher in Boston than in Birmingham.

What do the acts do?

Both acts have a variety of provisions to help those affected by COVID-19, but we focus only on the key unemployment-related components of the acts that benefit workers directly. By focusing only on workers, the analysis excludes components that provide incentives to employers to retain or rehire workers.

The CARES Act provides a direct cash infusion and expands unemployment insurance benefits. Individuals receive up to $1,200 in tax rebates and an additional $500 per qualifying child. The rebate begins phasing out when a person's income exceeds $75,000 (or $150,000 for joint filers). The CARES Act also suspends all payments on federal student loans through September 30 and pauses the accrual of interest. (See the CARES Act for details on which children are qualified and which loans are covered.)

The CARES Act also dramatically expands unemployment insurance (UI). On top of the regular state UI benefits, the federal government provides an additional $600 per week in the form of federal pandemic unemployment compensation through July 31. After an individual reaches the state maximum number of weeks on UI, emergency federal UI benefits extend the state UI benefits for up to an additional 13 weeks.

The FFCR Act suspends work requirements for determining Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) eligibility. Typically, single, able-bodied unemployed adults can only receive SNAP for a maximum of three months unless they are meeting other qualifying work requirements (for example, enrollment in training). By suspending work requirements, the act enables abled-bodied, unemployed adults without dependents to receive SNAP until the secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services lifts the declaration of the public health emergency.

Our case study: Introducing Chef Andrew

Chef Andrew is 25 years old and works full-time in a restaurant, earning the area-specific typical entry-level wage for chefs. He accumulated $5,700 in student loan debt, which is slightly higher than the first-year student annual maximum loan limit on the Stafford loan, and he makes monthly loan payments. He receives health insurance through his employer and pays a monthly premium. He rents an efficiency apartment, where he lives by himself, and he has no children. (Future macroblog posts will examine how the acts support families with children.)

On April 1, Andrew's hypothetical restaurant employer closed. He is laid off and unable to find another chef job since many other restaurants are also closed or operating in limited capacity. To highlight the benefits of the FFCR and CARES acts, we assume he remains unemployed for 10 months, a period that includes the maximum duration of assistance under the acts in Massachusetts—39 weeks—and an additional month of unemployment simply to illustrate his financial status without any of the acts' financial support.

Case study 1: Birmingham, Alabama

We first consider the situation when Andrew lives in Birmingham, Alabama. He earns $37,000 per year before taxes ($3,083 per month), which is the 10th percentile of chef wages in Birmingham. Every month he pays $700 in rent (fair market rent in Birmingham, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development), $143 for health insurance (the average cost of employer-sponsored health insurance for a 25 year old in Alabama, according to the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey), $100 towards his student loans, and $252 for basic groceries (based on the U.S. Department of Agriculture's low-cost food plan for a one-person household).

When Andrew loses his job, he qualifies for the maximum amount of $275 in unemployment compensation, which is about 36 percent of his regular gross weekly income. Before the COVID-19 measures, this amount is typically all he would have received through UI for a maximum of 14 weeks. Under the CARES Act, however, he is eligible to receive an additional $600 of federal pandemic unemployment compensation through July 31. The federal extended UI provides the same state UI amount for an additional 13 weeks.

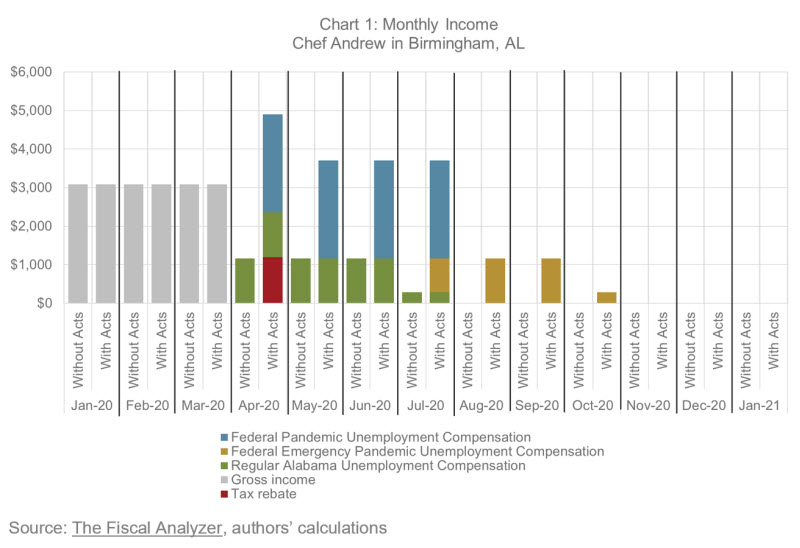

Chart 1 compares Andrew's sources of income with and without the acts for a period of one year, which is a long enough time period to show three months of pre-UI income and the maximum duration of available assistance under the CARES Act. April is his first month without employment income. Without the CARES Act, Andrew would receive only Alabama UI (represented by the green bars), which is around one-third of his typical employment income. He is eligible for Alabama UI for up to 14 weeks, after which the program ends and he has no source of income. With the CARES Act and assuming the distribution of act funds begins in April, his loss in employment income (represented by the gray bars) is offset—and more than offset in some months—by the tax rebate (represented by the red bar), the regular state unemployment insurance (green bars), the $600 federal pandemic unemployment compensation (represented by the blue bars) and federal emergency pandemic unemployment compensation (represented by the gold bars). These programs provide Andrew with financial support for a total of 27 weeks.

The CARES Act specifies that federal pandemic unemployment compensation is available only through the end of July, after which Andrew's income declines and he becomes eligible for SNAP. At this point, he continues to receive federal extended UI and begins to receive $29 monthly in SNAP. When in November he runs out of UI, he receives more SNAP assistance—$194 monthly—the maximum amount for a one-person household. Without the provisions in the FFCR Act, he would have received $29 monthly in SNAP benefits for a maximum of three months. Thus, when regular state UI ends, he would be without any sources of income and without food support payments.

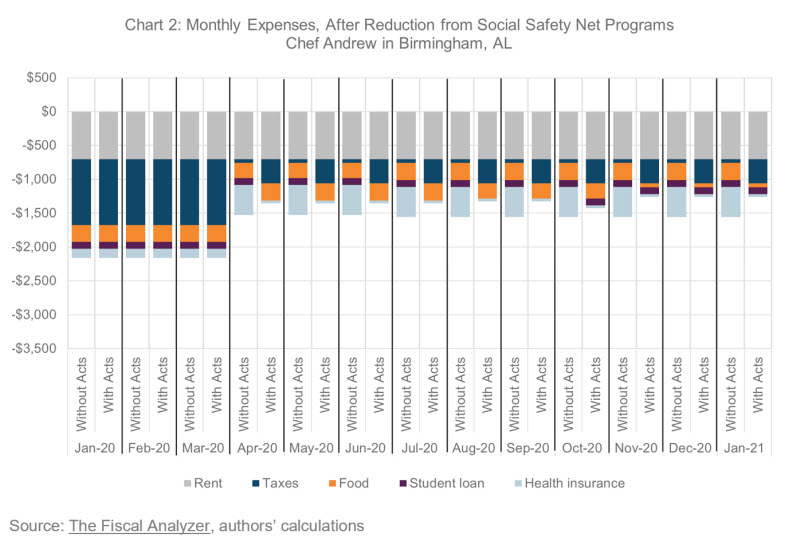

Chart 2 shows how both acts, together with the preexisting social safety net, reduce monthly expenses. For simplicity, we only include certain basic expenses that the pre-existing social safety net or the acts have the ability to reduce: housing, health insurance, food, and student loan payments.

When Andrew becomes unemployed, he loses access to employer-sponsored health insurance. In Alabama, able-bodied adults without dependents are not covered by Medicaid. Without the acts, Andrew's annual income when unemployed is below 100 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), which makes him ineligible to obtain a subsidized health care plan through the health exchange. Therefore, while unemployed, he pays health care expenses of $447 per month (the second lowest cost silver plan on the health exchange).

Under the CARES Act, he is able to defer his student loan payments through September 30, which reduces his expenses by $100 per month.

With the additional UI compensation provided by the CARES Act, his annual income is above the 100 percent FPL eligibility threshold, and he receives a subsidy under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which reduces his monthly expenses by about $400. At the same time, he pays taxes on the financial assistance from the government (except on the tax rebate, which is not treated as taxable income), which increases his monthly expenses by $355 compared to what they would be without the acts.

Case study 2: Boston, Massachusetts

Now let's suppose Andrew was an entry-level chef in Boston. He earns $34,472 per year before taxes ($2,906 per month), the 10th percentile of chef wages in Boston.Every month he pays $1,700 in rent (fair market rent in Boston, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development), $147 for health insurance (the average cost of employer-sponsored health insurance for a 25 year old in Massachusetts, according to the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey), $100 towards his student loans, and $252 for basic groceries.

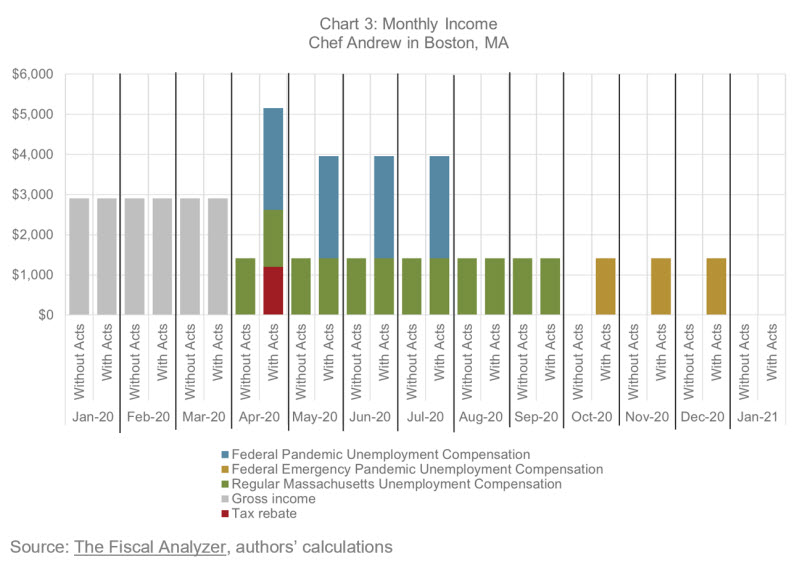

Chart 3 shows Andrew's sources of income with and without the acts. Under Massachusetts law, Andrew receives $335 in the unemployment compensation for 26 weeks (represented by the green bars). As in the Birmingham case, under the CARES Act, Andrew receives a tax rebate (represented by the red bar), federal pandemic unemployment compensation (represented by the blue bars). and federal emergency pandemic unemployment compensation (represented by the gold bars) for an additional 13 weeks. In total, without the acts, Andrew would have income support for 26 weeks in MA (compared to 14 weeks in Alabama). Likewise, with the acts, Andrew would have income for 39 weeks in Massachusetts (versus 27 weeks in Alabama).

With the FFCR, starting from August, Andrew is eligible for SNAP. While he is receiving state or federal extended UI, he receives $18 monthly in SNAP. When in January he runs out of UI, he receives more—$194 monthly—the maximum amount for a single person. As in the Alabama case, without the act Andrew is eligible only for a small amount of SNAP—$18 monthly—for the total duration of three months.

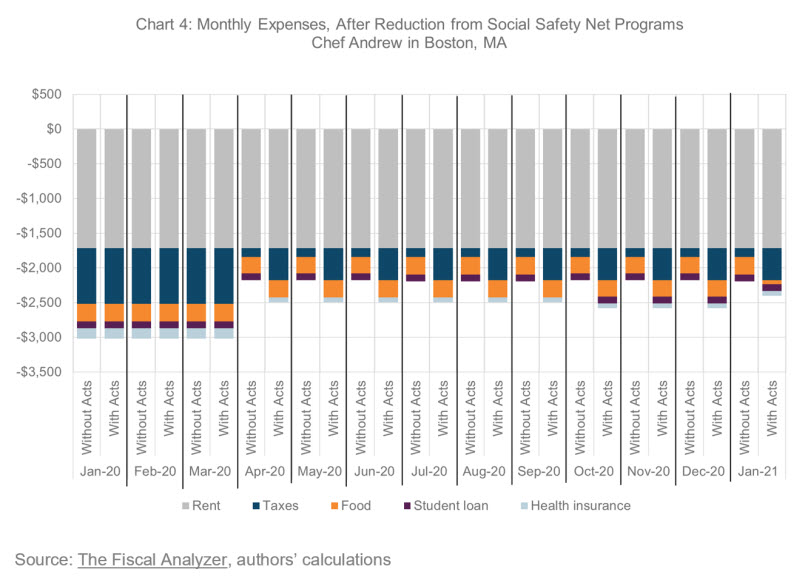

Chart 4 shows how the acts affect Andrew's basic living expenses if he lives in Boston. The most notable difference compared to the Alabama scenario is the cost of health insurance. Massachusetts does not have a Medicaid coverage gap. That is, able-bodied adults without dependents with income under the 137 percent FPL can receive coverage under Medicaid. Therefore, for the full duration of unemployment Andrew's health insurance premium is $0. (This is only true for the case without the acts. With the acts, Andrew is not eligible for Medicaid. However, he can receive a subsidy under the ACA and pays $68 per month for health insurance.

The CARES Act defers his student loans payments through September 30, which reduces his monthly expenses by $100.

A look at Andrew's net resources in both cities

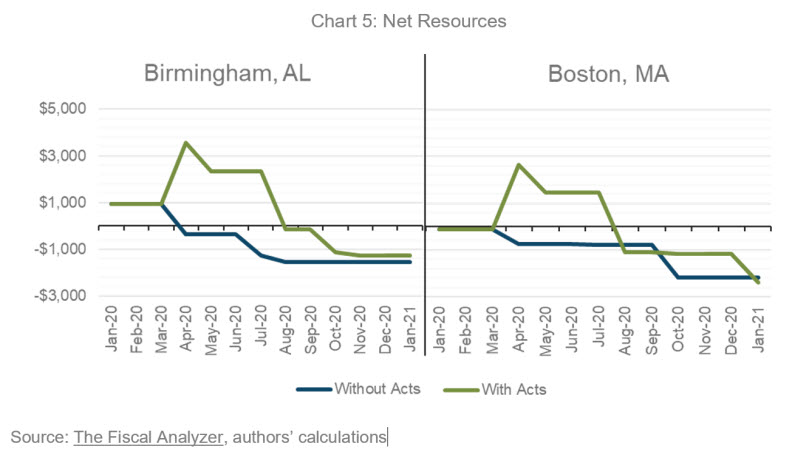

Chart 5 summarizes how the provisions in the FFCR and CARES acts, along with the preexisting social safety net, combine to support Andrew and help him pay his living expenses. The vertical axis on the chart shows net resources, which we define as the sum of after-tax income, SNAP, ACA health care subsidies, and assistance from the two acts, minus the basic expenses the acts created and safety net provisions. A value of net resources above zero can be thought of as the liquid savings in his budget that can be used to cover other expenses.

In Birmingham, before the crisis, he has about $1,000 of monthly slack in his budget. With the acts, he is able to meet most covered basic expenses until August (shown by the green line). In Boston, because of the slightly lower wage and higher living expenses, he cannot meet his covered expenses even before he becomes unemployed. Thus, in this period, he would likely have to borrow to make ends meet. The acts allow him to pay basic expenses also until August, when the net resources line drops below zero despite receiving more unemployment compensation and health care subsides. That again reflects significantly higher cost of living in Boston than in Birmingham (his monthly rent is $1,000 higher in Boston). Although Andrew receives federal extended unemployment insurance from October 2020 to December 2020, it does not cover Boston's high cost of living.

In conclusion, the potential impact of these current acts depends on the ultimate length of the unemployment spell, the variation in state UI laws, and the variation in the cost of living. Although this blog post illustrates a hypothetical case, the analysis does highlight the point that although the FFCR and CARES Acts should help to provide financial stability for many displaced workers in the short term, the size and duration of the acts' positive impact depends a lot on individual circumstances, including where they live. The longer the COVID-19 crisis persists, the greater the financial stress for many households will become—and the need for additional policy action will also become greater.

By Elias Ilin, a research associate at the Atlanta Fed and a PhD candidate at Boston University,

By Elias Ilin, a research associate at the Atlanta Fed and a PhD candidate at Boston University,