Chances are you recognize the relatively new acronym WFH as "working from home." In less than a year, WFH has become a ubiquitous, inescapable facet of life for many people, so much so that newswires now ask which cities are best for WFH, and online job boards compile lists

of companies that allow remote work on a full-time, permanent basis.

Many people are debating the pros and cons of WFH. For employees, gone are the long commutes and cramped cubicles, but other work-related stresses have emerged. As the pandemic drags on, some workers experience feelings of loneliness and isolation, health problems

, and challenges related to work-life balance

.

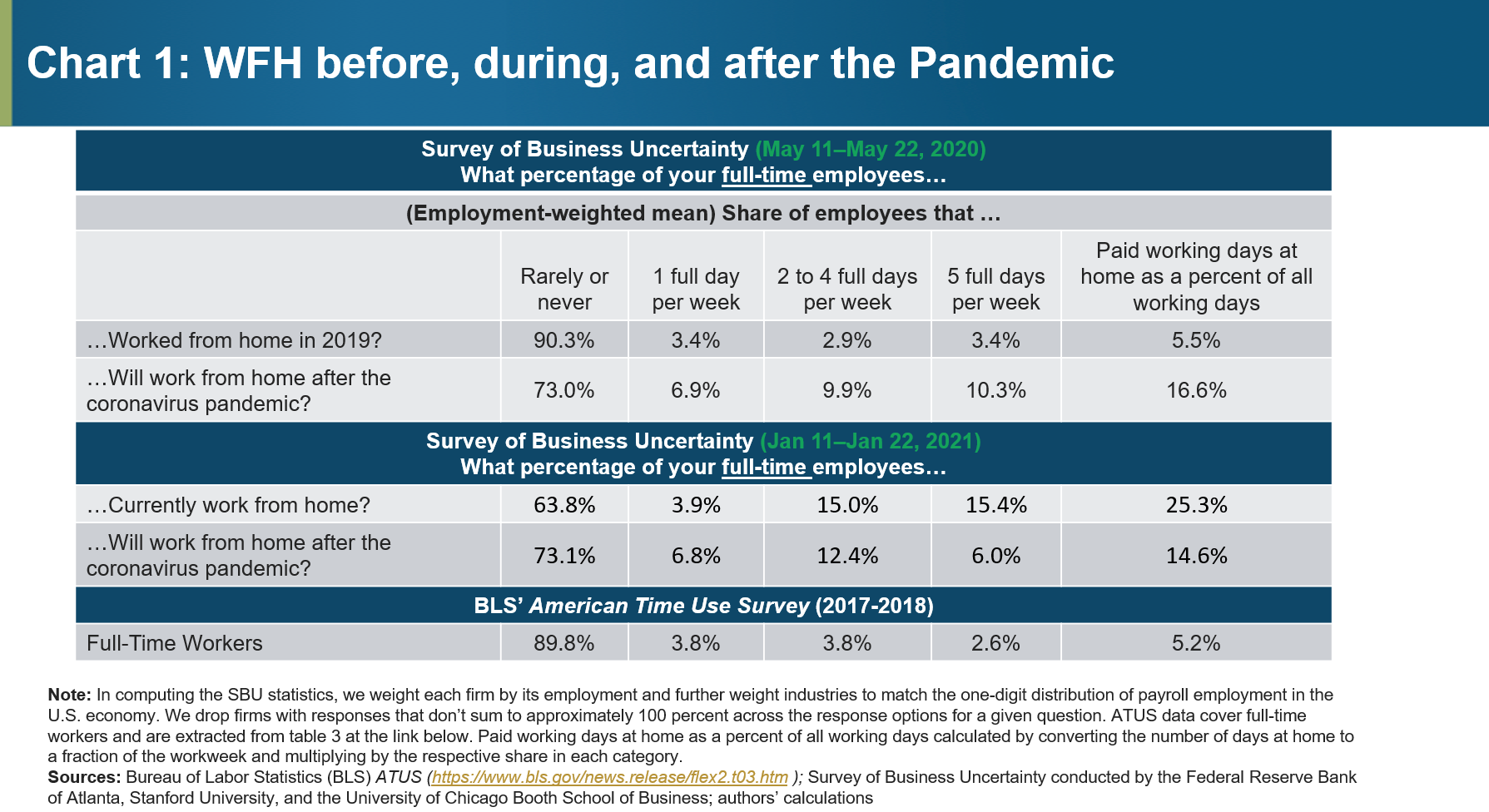

Back in May 2020, the Atlanta Fed's Survey of Business Uncertainty (SBU) elicited firms' views on WFH and found that, on average, firms anticipated that WFH would triple to 16.6 percent of paid workdays after the pandemic ends, up from 5.5 percent before it struck. Eight months later, we were curious to see whether and how plans had changed. So, in the January 2021 SBU, we asked two special questions very similar to ones we posed last May. Specifically, to gauge the extent of WFH, we asked, "Currently, how often do your full-time employees work from home?" To assess the future extent of WFH, we asked, "How often do you anticipate that your full-time employees will work from home after the coronavirus pandemic ends?" We asked firms to sort the fraction of their full-time workforce into six categories, ranging from five full days WFH per week to rarely or never.

It turns out that current plans are similar to those in May, with one important exception: firms increasingly favor a hybrid model for the postpandemic economy, walking back plans for the share of staff that will work exclusively from home.

Chart 1 summarizes the responses to WFH questions posed in January's SBU and compares them to our May results. We also compare the results to statistics computed from the American Time Use Survey, conducted by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics in 2017–18, which provides a useful benchmark. Aside from the striking similarity in pre-COVID levels of WFH across the surveys, several findings are worthy of note.

First, according to the January SBU, more than 35 percent of employees currently WFH at least one day per week. This estimate is plausible in light of work by Jonathan Dingel and Brent Neiman of the University of Chicago's Booth School of Business, which indicates that nearly 40 percent of U.S. jobs can be done at home . Moreover, the current WFH configuration tilts toward multiple days at home. All told, 25 percent of paid workdays are currently performed at home.

Second, firms report surprisingly similar figures in May 2020 and January 2021 for the share of employees whom they expect to work from home at least one day per week after the pandemic. Given the unprecedented nature of the pandemic recession, eight months is a long time over which to hold such stable expectations, suggesting that firms are serious about their intentions.

However, expectations have adjusted in one key respect: last May, firms anticipated that 10 percent of the postpandemic workforce would be fully remote, as compared to just 6 percent as of January. While still double the pre-COVID share, the revised expectation suggests many firms are coalescing around hybrid arrangements, whereby employees split the workweek between home and employer premises. These plans entail a large break from prepandemic working arrangements, but they imply more limited scope for employees to live anywhere—or for employers to hire from anywhere.

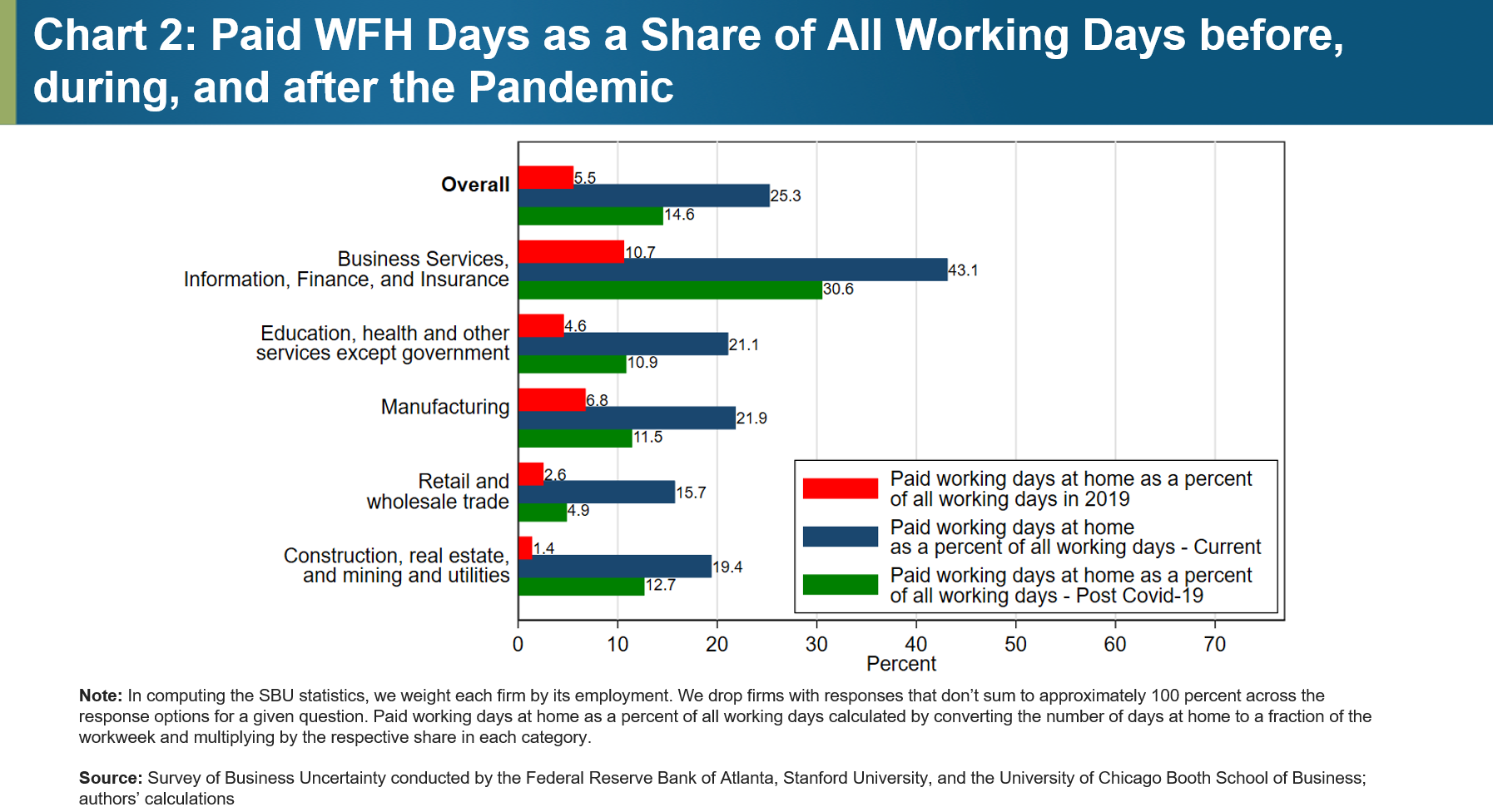

Chart 2 shows how the extent of actual and planned WFH varies by industry. Every major industry sector saw dramatic increases in WFH during the pandemic. With the exception of retail and wholesale trade, firms in every sector anticipate that a tenth or more of paid workdays by full-time employees will take place at home after the pandemic ends. For firms in business services, information, finance, and insurance, the postpandemic figure is 30.6 percent. And for the economy as a whole, it's 14.6 percent—nearly triple the prepandemic level.

Further digging into our survey results reveals the finding that COVID-19 shifted employment growth trends in favor of industries with a high capacity of employees to WFH and against those less able to accommodate remote work. Firms with a high WFH capacity experienced much higher stock returns in the past year than did firms with a low capacity. In addition, urban residences have become cheaper relative to suburban ones since the pandemic struck, suggesting that a shift to WFH has lowered the desirability of urban living

. More WFH also means fewer people commuting into city centers and less worker spending on meals, coffee, personal services, shopping, and entertainment near employer premises. A recent study finds that a permanent shift to WFH will directly reduce postpandemic spending

in major city centers by 5–10 percent relative to prepandemic circumstances. Of course, such changes also mean lower sales tax revenue for cities that had high rates of inward commuting before the pandemic.

To summarize, firms have largely stuck to their early expectations about the extent of WFH in the postpandemic economy. There has, however, been a notable drop in plans for employees to work from home five days a week. Remarkably, in every major industry sector except retail and wholesale trade, firms anticipate that WFH will account for one-tenth or more of full workdays by full-time employees, far above prepandemic levels. These shifts toward more remote work are driving a reallocation of jobs across industries and locations, contributing to fewer jobs, lower sales tax revenues, and lower property values in city centers. Our results suggest that these effects are likely to persist.