As the COVID-19 pandemic stretches into its second year, we've seen evidence of changes in how it, and attendant policy measures designed to support the economy, are affecting firms. Early in the pandemic, firms generally appeared more concerned with flagging demand and falling revenue than issues of having sufficient supplies (notwithstanding obvious acute issues at grocery stores). Rather, at least through August 2020, firms saw the COVID-19 pandemic as disproportionately a concern of demand rather than supply

—so much so, in fact, that firms scaled back on wages, expected to lower near-term selling prices, and lowered their one-year-ahead inflation expectations to a series low (going back to 2011). These findings, based on our Business Inflation Expectations (BIE) survey, are consistent with other academic research based on quarterly earnings calls of public firms

and research out of the Harvard Business School

.

However, as the pandemic continued to unfold and as relief and support continued to flow into the economy via ongoing monetary and fiscal policy efforts, many firms have begun to indicate a shift in concerns—from flagging demand toward concerns about fulfilling demand. Although the recovery remains decidedly uneven across industries, strong shifts in consumer activity (toward durable goods purchases) amid crimped production due to COVID-19 restrictions appear to have disrupted supply chains, to the extent that shipping containers sit mired in ports amid "floating traffic jams

." Along with these difficulties, firms continue to indicate issues with employee availability

, which hampers their operating capacity.

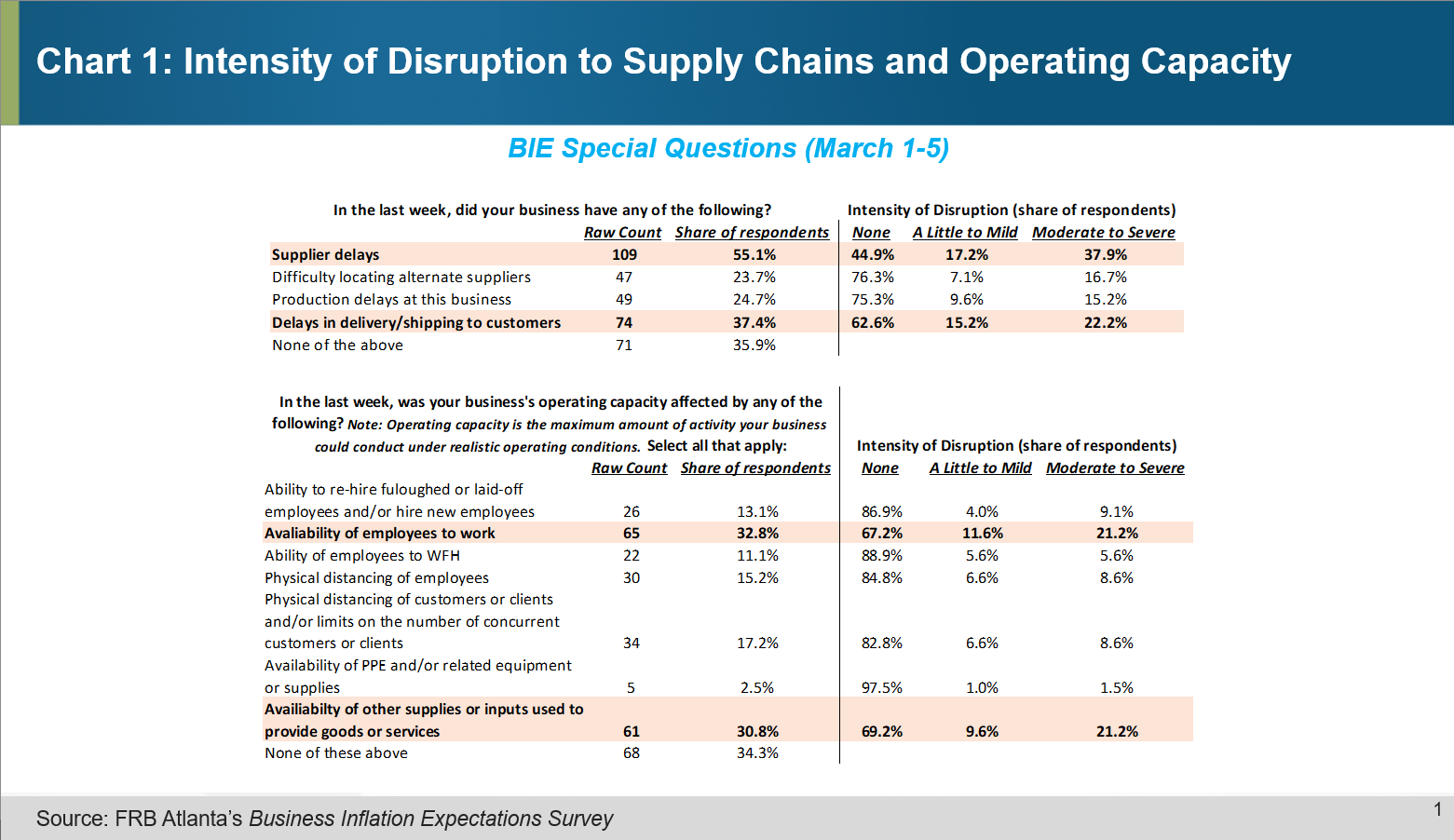

To investigate the breadth and intensity of these disruptions in supply chains and business operating capacity, we posed a few questions to our BIE panel during the first week of March. Specifically, we asked whether they'd recently experienced some form of supply chain disruption (anything from supplier delays to delays in shipping to their customers) as well as their experiences with crimped operating capacity (due to a variety of issues, ranging from employee availability to physical distancing issues). While we borrowed those two questions more or less directly from the U.S. Census Bureau's Small Business Pulse Survey, we also extended them by asking firms to gauge the intensity of these disruptions (on a scale ranging from "little to none" to "severe"). In addition, we posed these questions to medium-sized and larger firms in addition to those with fewer than 500 employees.

Chart 1 below shows the results. Regarding supply chain difficulties, we found that more than half of the firms in our panel felt some form of supplier delay, and the level of disruption is "moderate to severe" for 40 percent of them—a striking finding for a few reasons. First, our panel, like the nation, is disproportionately weighted toward service-providing firms (roughly 70 percent service firms to 30 percent goods producers). Second, just a few months ago (December 2020), firms ranked "supply chain concerns" as eighth out of their top 10 concerns for 2021. These results align with well-known diffusion indexes—the Institute for Supply Management Manufacturing and Business Services surveys—that have shown that a greater share of firms are experiencing slower deliveries and lower inventories in recent months.

In addition to issues receiving raw materials and intermediate goods from suppliers, a little more than one in three firms in the BIE panel also indicated that they themselves experienced delays in fulfillment, and the responses to the question on disruptions to operating capacity allow us some insight into the potential causes of these delays.

Here, a third of firms indicated that they were having difficulties with their employees' availability for work. Presumably, these issues stem from employees' concerns over contracting the virus, outbreaks causing production delays, or employees' inability to work due to familial issues such as childcare or the care of other dependents. One out of five respondents indicated that the intensity of disruption to operating capacity stemming from employee availability was moderate to severe. The same share of panel respondents—a fifth—indicated that a lack of adequate supplies and inputs on hand (likely due to supplier delays) caused a shortfall in production relative to capacity.

Comparing these responses to the Census Bureau's Small Business Pulse Survey, we find that the relative rankings of sources of disruption are quite similar—supplier delays far outweigh other supply chain disruptions, and the availability of employees for work are the most frequently cited sources of disrupted operations. Yet we find a greater incidence of disruption (even if we restrict our sample only to small firms). For example, 40 percent of firms surveyed by the Census Bureau indicated supplier delays, which slightly more than half of firms indicated to us. Such a discrepancy is unlike previous comparisons to other Census Bureau work (which match quite closely) and could be the result of a number of survey-specific factors. For instance, the types of respondents differ markedly—whereas the BIE elicits responses mainly from those in the C-suite and business owners, the census typically aims for someone in the accounting department. The number of response options also differs, and census respondents have seen these questions on disruption to supply chains and operating capacity numerous times over the pandemic.

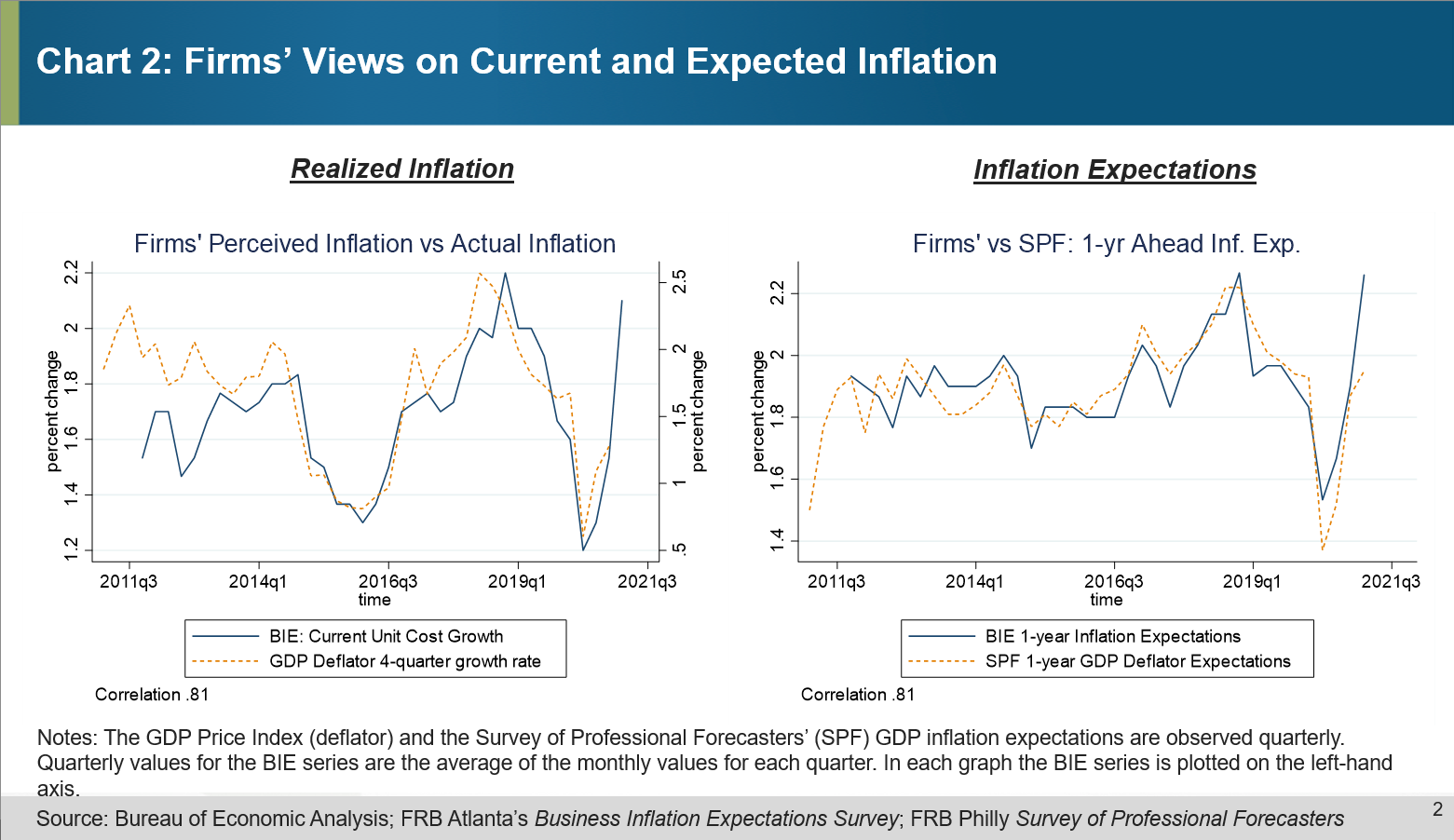

Although disrupted supply chains and crimped operating capacity are significant enough to warrant attention on their own merits, another aspect of these issues deserves attention. Concurrent with widespread supply chain disruption and hobbled operating capacity, firms have ratcheted up both their perceptions of current inflation and their expectations for unit costs going forward (see chart 2).

When we survey firms' expectations around inflation, we prefer to gauge their views on the nominal aspects of the economy through the lens of their own-firm unit costs, as other Atlanta Fed research shows. After falling to the lowest levels on record during the depths of the pandemic, firms' perceptions of unit cost growth over the past year have risen sharply. Interestingly, these perceptions correlate tightly with movements in official aggregate price indexes, such as the gross domestic product price index (also called the GDP deflator) and the personal consumption expenditures price index.

Firms also appear to anticipate higher unit-cost growth in the year ahead. Since hitting a low in April 2020, firms' unit-cost (basically, inflation) expectations for the year ahead have surged to all all-time high just 11 months later. Not only does that kind of volatility speak to the dramatic and disparate impact COVID-19 has had on business activity, but it also suggests that the underlying drivers of these expectations have shifted markedly. (Incidentally, chart 2 shows that this measure of firms' inflation expectations moves in lockstep with professional forecasters' views.)

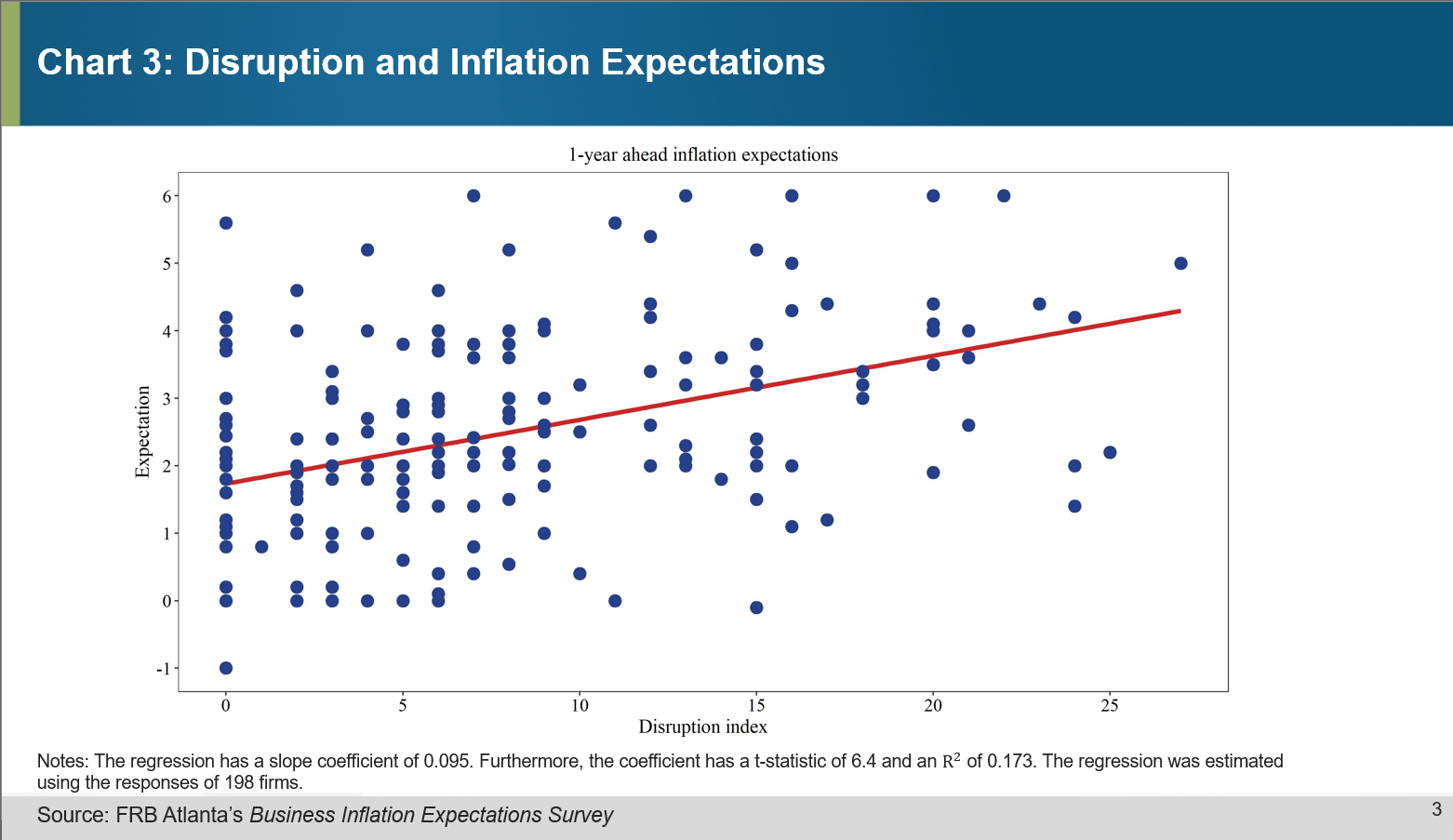

Indeed, in sharp contrast to their views early in the crisis, firms' one-year inflation expectations appear to have risen sharply alongside their views on supply chain and operating capacity disruption. Chart 3 shows a simple scatterplot between firms' one-year-ahead inflation expectations and a summary measure of the intensity of their disruption. To create this measure, we first assigned a score from 0 to 4 to each special question response based on whether they responded "None," "Little to none," "Mild," "Moderate," or "Severe." We then add their scores to obtain their disruption index. The mean disruption index value for firms in goods-producing industries is 9.3 and 6.6 for service-providing firms. And consistent with anecdotes and news stories, the disruption is highest in manufacturing industries (9.75) and trade and transportation industries (9.1).

Chart 3 visualizes the relationship between inflation expectations and the index of supply chain disruption. Although supply chain disruption isn't the only factor influencing year-ahead unit cost expectations, we can see that firms with the largest levels of disruption tend to be those that hold higher expectations for inflation in the year ahead.

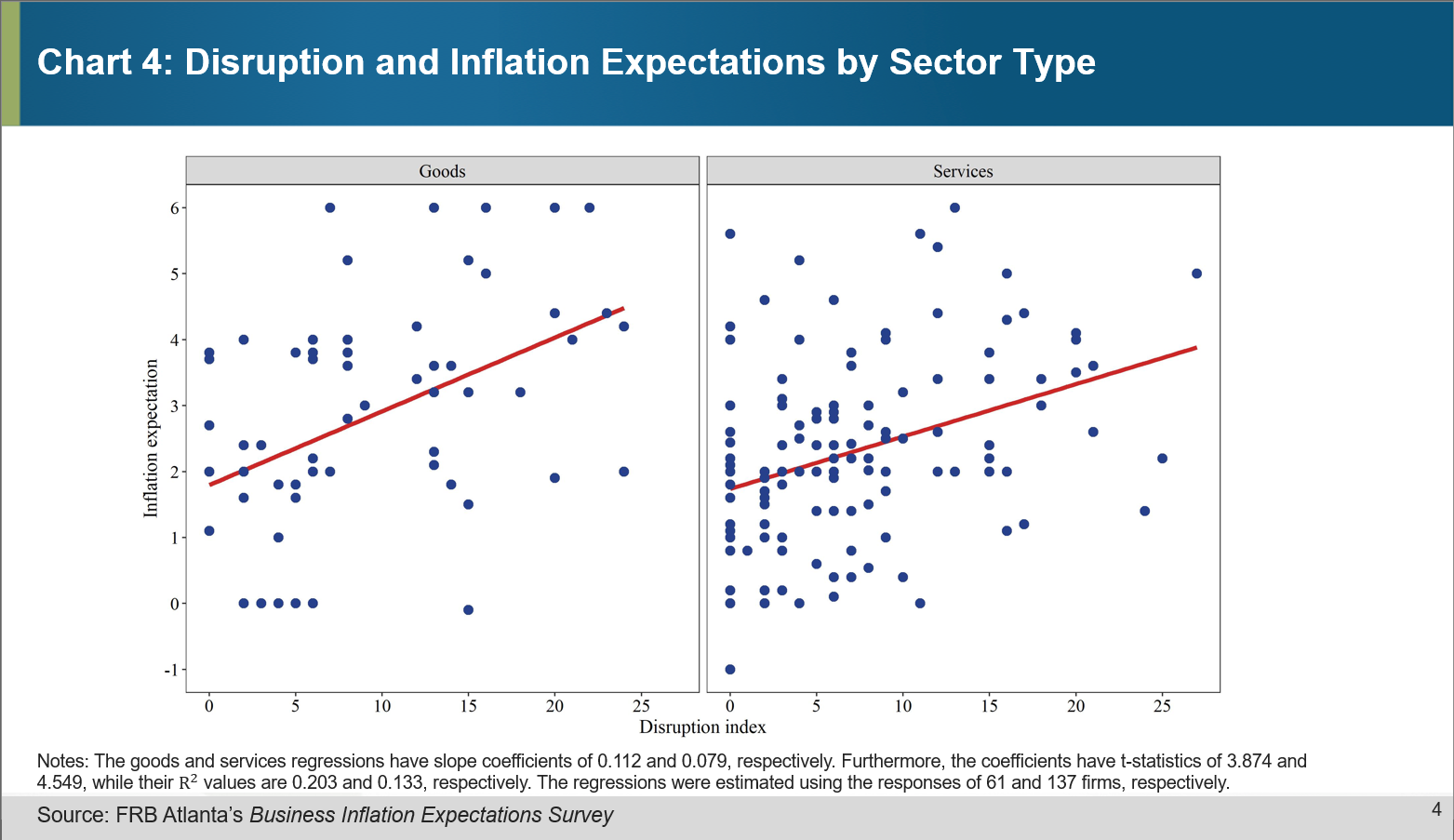

For another perspective, chart 4 shows that the relationship between inflation expectations and disruption depends on whether the responding firm belongs in the goods-producing sector or the service-providing one. While both have strong positive relationships, it's interesting to note that the relationship is even stronger among firms in the goods-producing sector. While perhaps an unsurprising result, it is a reassuring one given that the most-cited reason for supply chain disruptions—supplier delays—is more likely to affect goods-producing firms.

Overall, when one contrasts the early portion of the pandemic with the more recent period, significantly more firms indicate that they are experiencing disruptions in their supply chain and operating capacity. More than 50 percent of our survey panelists indicated delayed deliveries from suppliers (and for most of those respondents, the disruption is moderate to severe). Combined with crimped operating capacity due largely to uncertain employee availability and lack of inputs, firms are beginning to view these disruptions as factors that are driving up their unit costs and leading to higher inflation expectations. We can connect the dots from firms' year-ahead inflation expectations to the intensity of these supply and production disruptions. Firms experiencing the most intense disruption tend to be those with the highest expectation of future inflation. This explanation tamps down the speculation that the potential inflationary impact of recent fiscal stimulus on demand is behind heightened year-ahead inflation expectations.