Last week, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) again decided to raise the federal funds rate target by 75 basis points in an effort to help curb inflation. While Chair Powell, in his press conference following the July FOMC meeting, noted the lag in monetary policy's influence on inflationary pressures, he also pointed out that "if you have a sustained period of supply shocks, those can actually start to undermine or to work on de-anchoring inflation expectations" (see the 16-minute mark of the video

![]()

from the press conference).

We, too, share this worry. In fact, it's been something we've been concerned about here at the Atlanta Fed since last fall. In a speech at Peterson Institute speech in October 2021, Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic said: "I continue to believe currently elevated inflation is episodic, driven by pandemic conditions such as disruptions in supply chains and labor markets. A major caveat, though, is that the severe and pervasive supply chain issues will probably last longer than most of us initially expected. Up to now, indicators do not suggest that long-run inflation expectations are dangerously untethered. But the episodic pressures could grind on long enough to unanchor expectations."

After monitoring the evolution of our Business Inflation Expectations (BIE) survey data for the better part of a year, we're still concerned. While the BIE has only been around since 2011, and the current period of high inflation is the only shock we've picked up in our data, the speed and sharpness of the increase in our survey-based measure of inflation expectations have left us wondering: How unsettled are longer-run inflation expectations?

For those not familiar with the BIE survey and its unique perspective on firms' inflation expectations, it's a monthly regional survey that the Atlanta Fed conducts to measure firms' inflation expectations in the Sixth District. Rather than elicit firms' aggregate inflation expectations, we ask them about their own-firm unit cost expectations—an input that is directly related to their own-firm price formation strategies (see Meyer et al. 2021). Moreover, the expectations we elicit are probabilistic, meaning we can gauge not only an individual firm's average expectations but also the level of certainty with which firms are holding those views. What does the BIE tell us about how firms are reacting to the highest bout of inflation the United States has experienced in 40 years?

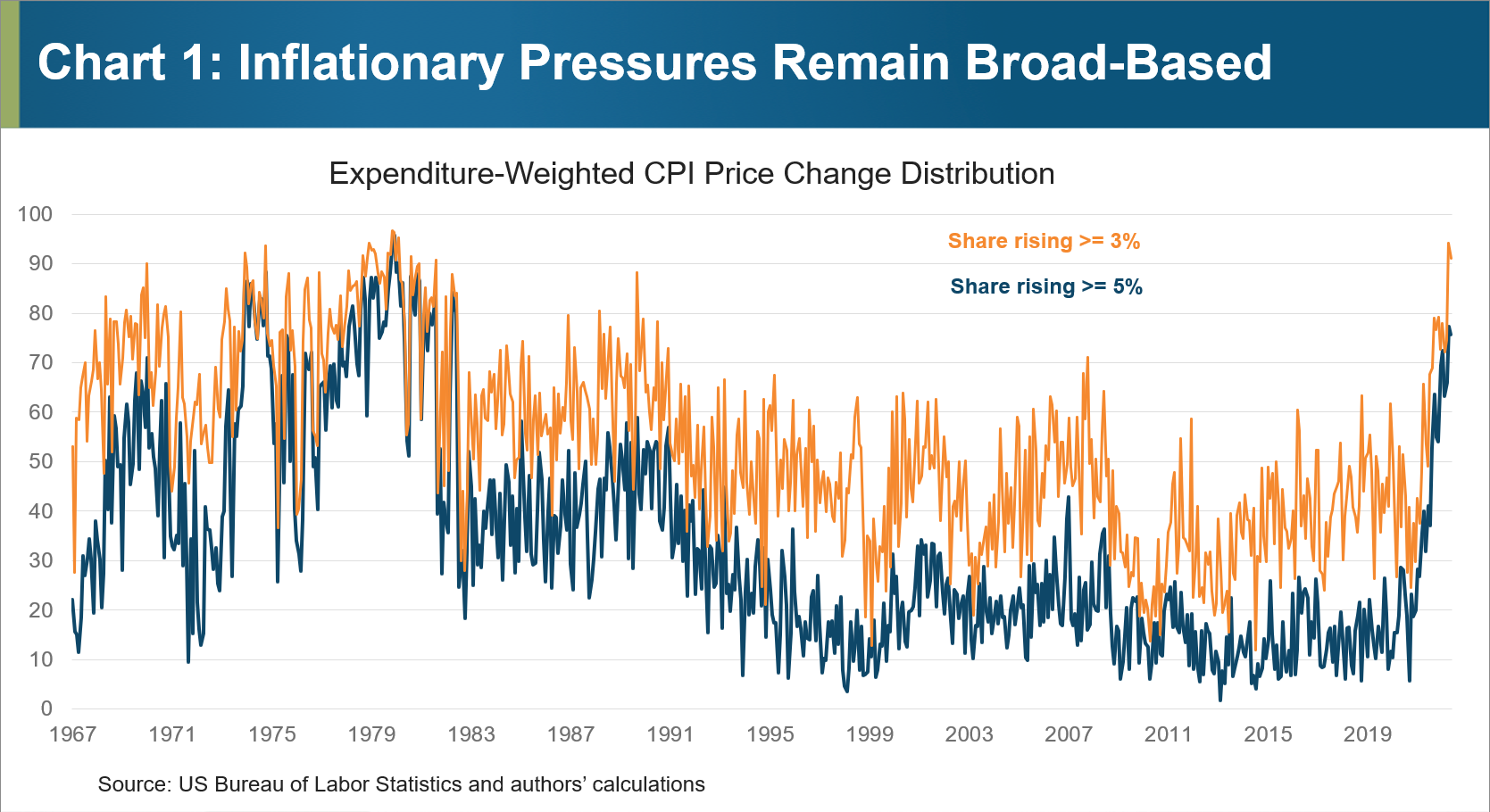

By now, the current inflationary environment should be apparent to just about everyone. It's affecting all areas of the consumer market basket and has become a recurring headline in the news. It's even become a popular search term on Google. In fact, inflationary pressures have risen to heights that we haven't seen since the early 1980s, during the period known as the Great Inflation. As the chart below shows, roughly three-quarters of prices in the consumers' market basket (by expenditure weight in the consumer price index, or CPI) have risen at rates equal to or exceeding 5 percent (see chart 1). In June, more than 90 percent of prices in the market basket outpaced the 3 percent mark.

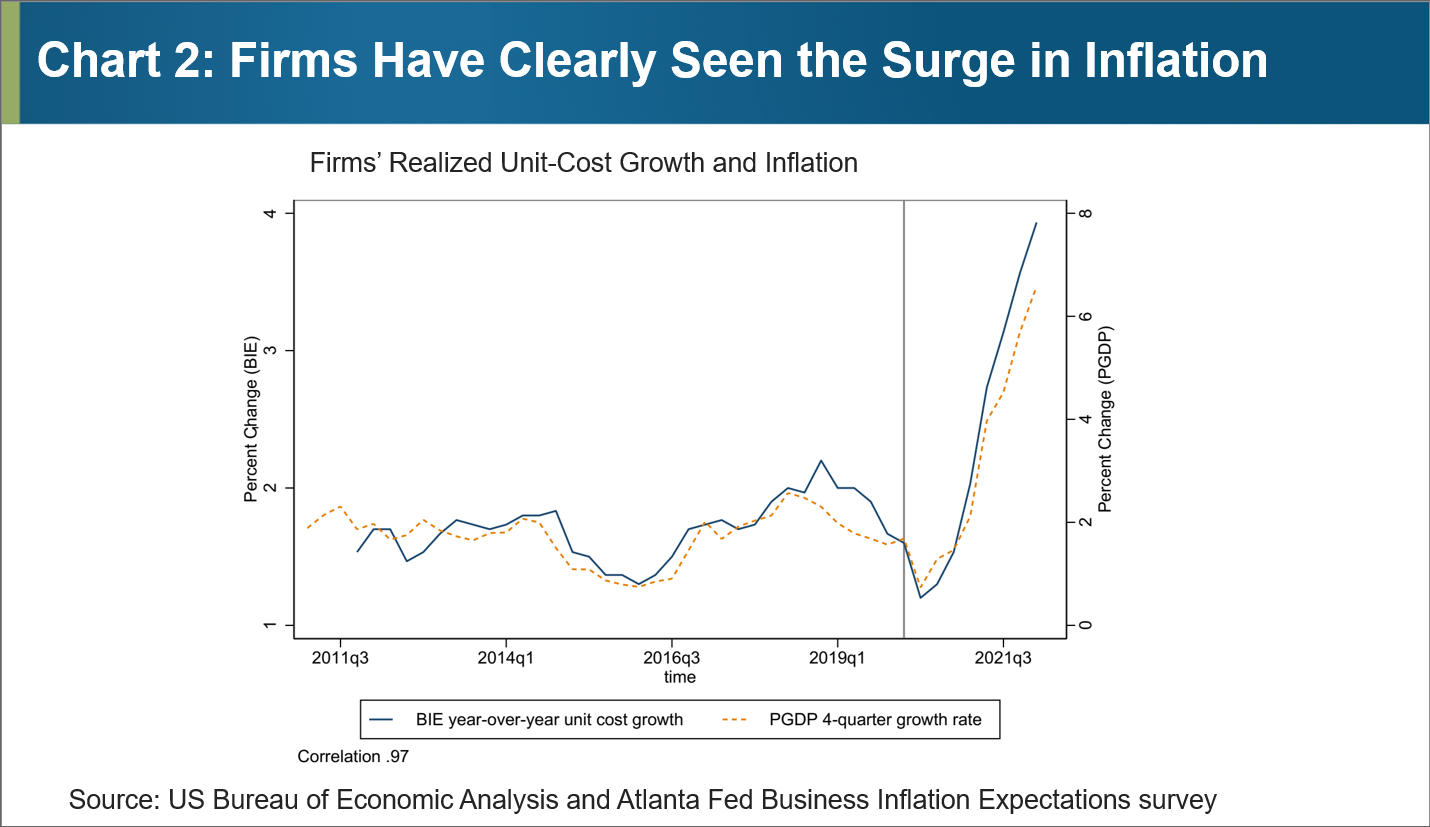

This high-inflation environment is not lost on businesses. In fact, firms' perceptions (unit-cost realizations) have been highly correlated with the evolution of overall inflation over the course of the pandemic. Chart 2 plots firms' realized unit-cost growth over the past year and compares it to the year-over-year growth rate in overall inflation as measured by the GDP price index, which is the broadest measure of inflationary pressures as it goes beyond just consumer prices to gauge price pressures in the entire economy.

In the world of survey-based measures of inflation expectations, our BIE survey has one clear advantage: not only can it track the evolution of expectations but it can also provide clear insight into firms' perceptions of the current environment, which is very useful in gauging the external validity of those expectations. To us, this insight compellingly shows that firms in our BIE panel are clearly seeing the facts when it comes to inflation.

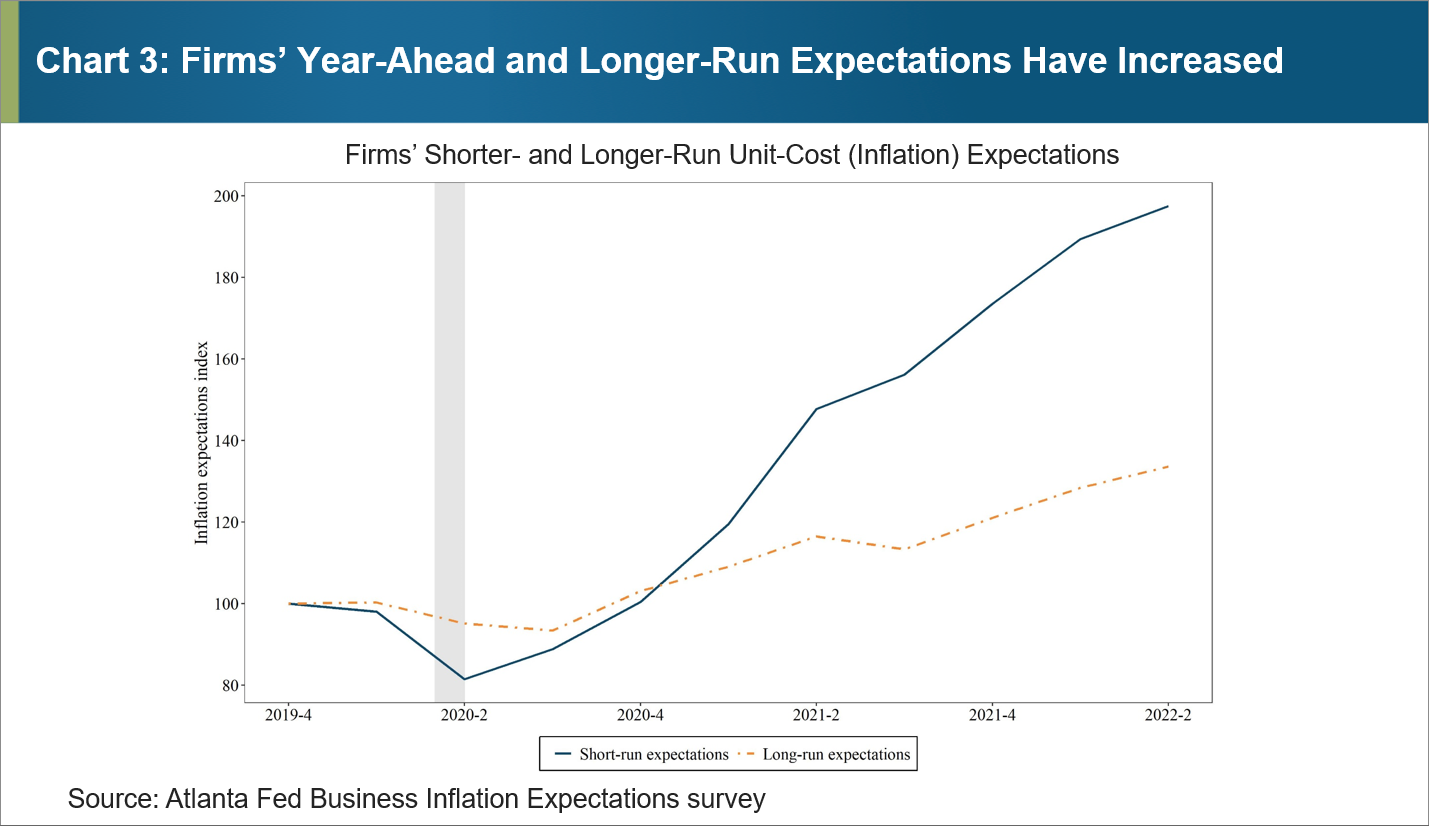

When general prices increase, businesses' input costs also increase, and as higher costs squeeze margins, many firms will pass some or all of those costs on to their customers in the form of (you guessed it) higher prices. Survey evidence suggests a correlation between supply chain disruptions and higher year-ahead inflation expectations. We've previously noted that although supply chain disruption isn't the only factor influencing expectations, firms with the largest levels of disruption tend to hold higher expectations for inflation in the year ahead (see chart 3). So what are firms telling us about their expectations for the evolution of inflation over the year ahead and beyond?

Perhaps the easiest way to see how much both short-run and five-year-ahead (long-run) inflation expectations have moved over the past two years is to index them to their prepandemic growth rates. In chart 3, we depict these expectations, indexing each series to 100 in the fourth quarter of 2019. What we can see is that both short-run and longer-run expectations have increased dramatically.

While initially short-run expectations dipped at the start of the pandemic (amid widespread lockdowns and a substantial decline in economic activity), starting early in 2021, firms' short-run inflation expectations began to increase sharply. Later in 2021, firms' long-run expectations also started to show a meaningful pickup. Firms' short-run inflation expectations have roughly doubled relative to the prepandemic period. And firms' longer-run expectations are about 25 percent higher than the expectations we saw in late 2019.

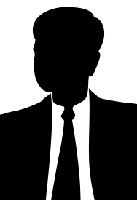

We can dig a bit deeper into firms' longer-run expectations by examining the average probability weights that firms assign to the potential outcomes for longer-run unit costs at different periods, as chart 4 shows. In this case, we look at the fourth quarter of 2019 and the second quarters of 2020, 2021, and 2022.

These histograms illustrate the degree to which firms' inflation expectations have shifted over the course of the pandemic. Here, two aspects of this shift stand out to us. First, through the middle of 2021, even as inflation metrics were beginning to heat up, the distribution of firms' longer-run expectations hadn't moved much. Second, during the past year, the average probability distribution shifted starkly. The typical firm in our panel is now assigning nearly a 60 percent probability to longer-run unit cost increases of at least 3 percent per year. Moreover, their modal expectation is for longer-run unit costs to increase by 5 percent or more annually—which means that more firms anticipate the need to adjust their unit costs by more than 5 percent per year in the long run. To put this bluntly, we haven't witnessed anything like this in the decade-long existence of this survey.

A couple of caveats are worth mentioning here. First, although this is the first sizable "inflation shock" we've been able to examine in the BIE survey, we do not have a long enough time series to compare the current era to the aforementioned Great Inflation. At best, we can suggest that—given the high correlation between firms' unit-cost expectations and professional forecasters' expectations—our measures would have performed similarly in the '70s and '80s. Also, as the extensive literature on consumer expectations documents, the possibility exists for business executives to base their projections for future unit costs solely on current conditions (a phenomenon economists call adaptive expectations). Still, that last point cuts two ways. First, it's possible that, should inflation ebb meaningfully in the coming months, these longer-term expectations might follow suit. Conversely, persistently high inflation could further cement such expectations for the longer run, making it more challenging for policymakers to bring inflation back to their price-stability goals.

Said another way, the current bout of high inflation is unusual in many different ways, and how it will play out remains fraught with uncertainty. Firms' short- and long-run expectations have risen sharply, and longer-run expectations show a clear rise in the average firm's probability distribution, to the extent that nearly one-third of the weight is being assigned to anticipated cost increases greater than 5 percent. So as we continue to delve further into these expectations and monitor upcoming developments, we're left pondering the question: is this how "unanchoring" begins?