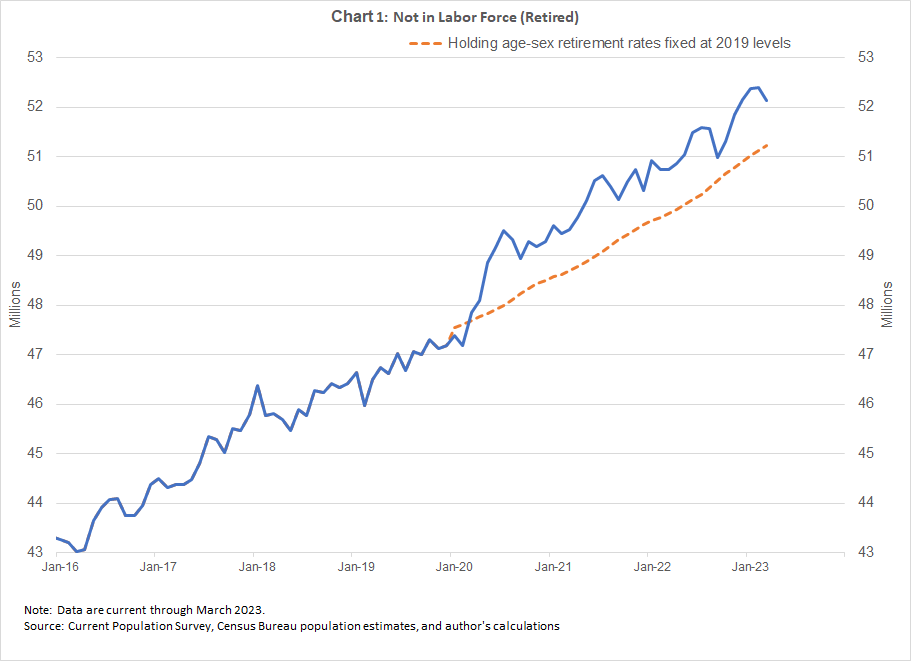

As I enter my sixties, the notion of retirement crosses my mind more often—and apparently I'm not alone. By my estimation, there are about five million more retirees in early 2023 than there were immediately prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Chart 1 shows this increase, with the blue line depicting the estimated number of people who are not in the labor force and say they are retired.

As a technical aside, the data in the chart are corrected for population estimates based on the 2020 decennial census. The revised data imply fewer retirees in the years before 2020 than the population estimates based on the 2010 decennial census indicate.

The chart clearly shows a jump in the number of retirees with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. I find that, of the five-million increase in the number of retirees since 2019, roughly one million can be attributed to a change in retirement behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. That is, if retirement rates for each sex-age combination had stayed the same as they were on average in 2019, there would have been about four million more retirees simply because of the aging population. (See this study by my colleagues at the Board of Governors for related analysis on this topic.)

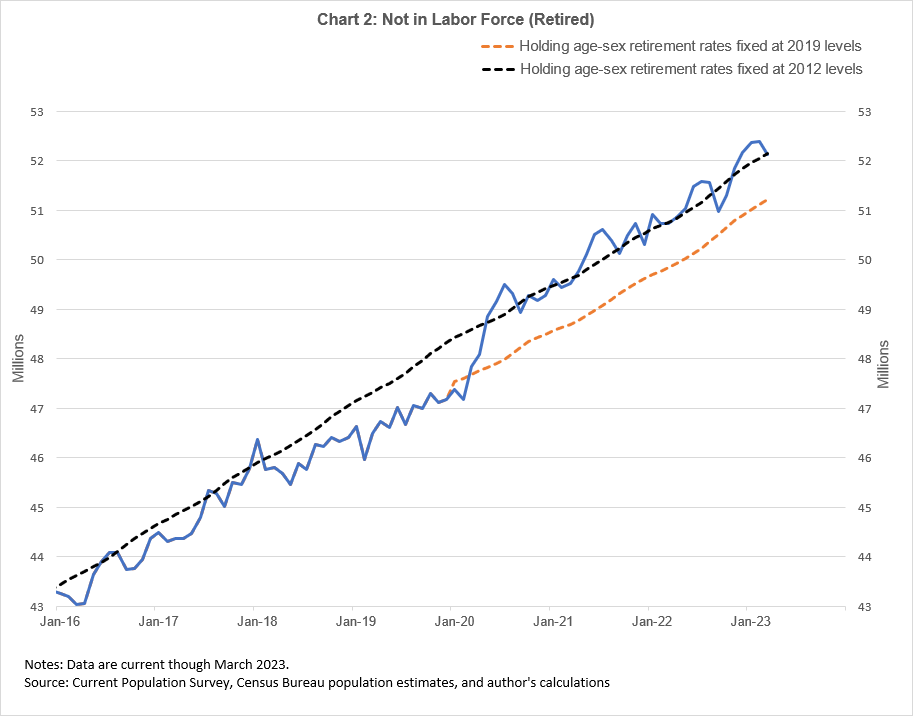

Interestingly, the couple of years leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic was a period of rising participation rates across all ages, responding in part to the tight labor market conditions that existed at the time (see, for example, this study that was presented at the 2021 Jackson Hole symposium). These conditions helped suppress retirement rates by keeping people engaged in the labor force. To see how this affected retirement numbers, I ran an experiment that held age-sex retirement rates fixed at their average levels in 2012 (see chart 2). (I choose 2012 as being representative of the period recovering from the Great Recession of 2008–09.) My analysis, which also used the demographics of aging from 2012, would put the number of retirees close to where it actually is today. Chart 2 shows this experiment, where the black dashed line shows the estimated number of retirees based on 2012 retirement rates.

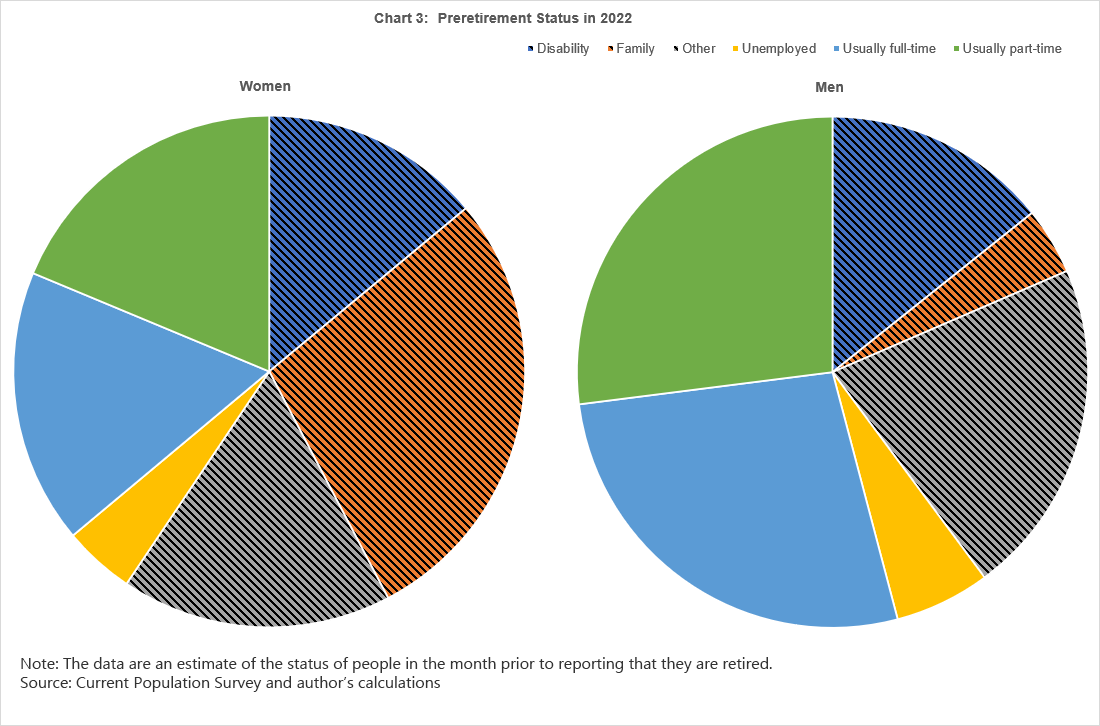

What are the labor supply implications of increased retirement? One thing to keep in mind is that rising retirement numbers don't translate to a commensurate decline in the size of the labor force, because many people who enter retirement were already out of the labor force prior to retirement. For example, someone who was at home taking care of household responsibilities, and thus not counted as a participant in the labor force, might say they are retired once their working spouse or partner retires. Similarly, someone who had been too sick or disabled to work but is now eligible for retirement benefits might say they are now retired although their health is unchanged. Changing from one nonparticipation category to another doesn't affect the number of labor force participants. Chart 3 shows the distribution of preretirement categories of new retirees. I've aggregated the data to an annual frequency to smooth out any seasonal fluctuations. The crosshatched colors identify preretirement activities that are outside the labor force, and the solid colors identify activities within the labor force.

Around 60 percent of women who moved into retirement during 2022 were not in the labor force immediately prior to retirement (the hatched area of the chart). The largest preretirement category for women was "family responsibilities" (28 percent). For men, about 40 percent were not in the labor force for several years prior to retirement, with "other reasons" being the largest nonparticipation category (20 percent). Also notice that part-time and full-time employment are about equally important preretirement characteristics for both men and women, but because more men than women are labor force participants, moving from employment to retirement is generally more common for men than for women.

The aging population is clearly a powerful influence on the labor force. A recent blog post by my colleagues at the New York Fed argues that the aging population is behind almost all the shortfall in the overall labor force participation rate relative to pre-COVID. Importantly, an aging population is likely to continue to pressure the labor force in coming years. A January 2023 study

by the Congressional Budget Office projected that between 2023 and 2053 the number of people aged 65 and older will increase by 25 million (an average rate of 1.2 percent per year), whereas the prime working-age population (defined as those aged 25–54) will have increased by only eight million (an average rate of 0.2 percent per year). Moreover, immigration will increasingly drive projected prime-age population growth as US birth rates remain below the rate necessary for a generation to exactly replace itself.

Absent faster growth in the working-age population through increased immigration, boosting the growth rate of the labor supply will need higher labor force participation rates. Encouragingly, this is something that we have started to see in recent months among the prime-age population. For example, a tight labor market has helped to increase prime-age labor force participation, which has increased from 82.5 percent in March 2022 to 83.1 percent in March 2023 and is the same as its pre-COVID level. However, prime-age participation is still well below the 84 percent level seen in the early 2000s. For the older population, especially those over 65, participation rates remain well below pre-COVID levels (currently around 19 percent versus 21 percent pre-COVID), suggesting that, in the wake of the pandemic, the desire and willingness of older Americans to work might have permanently changed. That said, one of the lessons I have learned over my career studying labor markets is that while demographic changes are slow and reasonably predictable, behavioral changes can be fast and are much less easily anticipated. During the 1990s, reforms to social security and a shift away from defined-benefit pension plans had a significant impact on older workers' participation in the labor force. Lost retirement savings during the Great Recession also lifted participation behavior. In that regard, according to the Federal Reserve's Distributional Financial Accounts overview, the net worth of older American's is around 25 percent higher than it was in 2019 but is down by about 3 percent at the end of 2022 from a year earlier. So never say never.