Notes from the Vault

Larry D. Wall

May 2020

The aggregate allowance for credit losses (ACL) at a set of large banks increased by 65 percent in the first quarter of 2020.1 The increase was due in approximately equal parts to two developments. First, the banks increased their ACL on January 1 to conform to a change in the method of estimating credit losses, from the incurred loss model to current expected credit loss (CECL). Second, the banks increased their ACL to cover an increase in expected credit losses. The magnitude of the ACL increase—commonly referred to as a "build"—at each bank depends on a variety of factors, but banks typically cited the increase in expected losses due to COVID-19 as a major determinant. This post reviews the change in accounting standards, provides some context for the ACL build, and explores the first-quarter increase in greater detail.

Change in accounting standards

In June 2016, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) issued Accounting Standards Update 2016-13, Topic 326, Financial Instruments–Credit Losses, which adopted a new way of estimating credit risk for financial instruments accounted for at amortized cost. From the perspective of most banks' ACL, the smaller part of the change was the application of a single methodology across credit exposure classes (loans, loan commitments, and securities) where there had been multiple methodologies. More importantly, from most banks' perspective, is the replacement of the incurred loss model with the current expected credit loss methodology for estimating losses in banks' biggest source of credit risk—their loan portfolio.2 The incurred loss model only allows losses to be measured if it is probable they have already been incurred. CECL requires that losses be based on estimates of expected losses under future economic conditions.

The adoption of CECL has generated considerable controversy in some quarters.3 The main arguments for and against it can be summarized as follows. Probably the strongest argument for CECL is that the loss estimates provided by the incurred loss model were not credible with market participants during the Great Recession.4 The incurred loss model resulted in banks delaying the reporting of credit losses until long after it was apparent the banks would suffer increased losses. The resulting loan loss provisions were widely criticized as "too little, too late." The lack of credibility in reported allowances necessitated the Federal Reserve's 2009 stress tests of banks so that market participants and supervisors could obtain credible estimates of likely credit losses. CECL addresses this by requiring bank financial statements to reflect all changes in the expected value of credit losses in the period in which those expectations change.

One of the main conceptual arguments against CECL is that it would result in procyclical provisions for credit losses. That is, ACL would likely decline during boom times and sharply increase during recessions unless the banks had perfect forecasts of future economic developments, especially the turning points of the economic cycle. The incurred loss model is also procyclical, but it tended to delay and spread the increase over a larger number of quarters as banks awaited confirmation that the losses had become "probable." A second conceptual argument is that since almost all loans involve some risk of credit loss, CECL would require provisioning for even newly made loans. The practical objection to CECL implementation is that the estimates would depend upon banks developing procedures and making estimates of economic activity that had not previously been required for financial accounting.

Both the FASB and the bank regulators responded to the concerns about CECL, albeit not to the degree desired by some banks. FASB's response in October 2019 was to delay CECL's effective date to January 2023 for private corporations and public firms that met the Securities and Exchange Commission's (SEC) definition of a "smaller reporting company." This provided more time for those banks with fewer resources to prepare.

The issue for the bank regulators is how to incorporate the increase in ACL due to the new accounting standard into existing regulatory measures of bank capital adequacy. The adoption of CECL will generally result in a higher ACL, which would result in a reduction in regulatory capital adequacy measures.5 The likely upshot of this would have been that banks would have lowered their asset growth rates and reduced capital distributions in order to rebuild their regulatory capital ratios. Rather than force banks to make the full adjustment to CECL over a short period of time, the bank regulatory agencies on December 21, 2018, announced a three-year transitional period for phasing in the impact of CECL on capital ratios. However, by March 27, 2020, it was apparent that the United States would enter a steep recession as a result of the private and public responses to COVID-19. The bank regulatory agencies decided that if CECL induced a marginal reduction in bank lending, that would likely have the effect of making the COVID-19 economic downturn even worse. Thus, the agencies offered banks the option of delaying the estimated effect of CECL on regulatory capital measures for two years, followed by a three-year transition period.

Congress also responded in March to concerns about CECL in Section 4014 of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act), by giving banks the option to delay their adoption of CECL until the earlier of the president terminating the national emergency declared for the novel coronavirus or December 31, 2020. Some banks that would otherwise have been required to implement CECL took advantage of this opportunity, according to an article by Bloomberg reporters Nicola M. White and David Hood. However, all of the large banks eligible for this study elected to proceed with the adoption of CECL. Among the explanations given are that the CARES Act did not delay adoption for very long, these banks were already prepared to implement CECL (see here), and the regulatory action delaying the impact of CECL on capital ratios removed a major incentive to delay adoption.

COVID-19 lockdown shock to the financial system

The novel coronavirus COVID-19 went from not being considered a factor in late 2019 economic forecasts to causing severe economic disruption early this year. In the first two months of 2020, the economy started out reasonably strongly. However, a combination of privately determined and governmentally mandated social distancing led to a substantial economic downturn as the month of March progressed. This reduction in economic activity would be expected to reduce bank borrowers' ability to service their debt and lead to increased loan losses. The issue for the credit loss allowance is that it is estimating the magnitude of expected losses.

The estimate of loan losses in CECL is explicitly forward looking, requiring an estimate of expected losses on all loans based on economic forecasts. CECL is not prescriptive about how to form such forecasts but rather requires the forecasts to be "reasonable and supportable." The estimate of losses using "reasonable and supportable" models requires banks to estimate the strength and duration of the COVID-19 downturn. This estimate is necessarily going to be based on economic conditions at the end of the reporting period.

The high degree of uncertainty about the economy and credit losses was widely reflected in my review of banks' discussion of their first-quarter results, including their increase (or build) of their allowance for credit-related losses. They often discussed the potential for future significant increases in the allowance, depending upon how the economy developed. As events have developed, it appears those warnings were appropriate. As one metric of how forecasts have changed, the consensus of Blue Chip Financial Forecasts (2020a) of top forecasters reported on April 1 was that the peak in unemployment in 2020 would climb to 9.6 percent. A month later, the May 1 Blue Chip Financial Forecasts (2020b) had the peak unemployment rate nearly doubling to 17.5 percent.

Although it is virtually certain that CECL is forcing banks to increase their allowances for credit losses during the COVID-19 downturn faster than would have been the case under the incurred loss model, exactly how much is difficult to estimate. Banks generally limited their discussion of estimated losses to their estimate measured in accordance to CECL. Kroll Bond Rating Agency recently argued, "Old GAAP [generally accepted accounting principles, a reference to the incurred loss model] or CECL may not make much difference this time."6 Kroll's rationale is that the downturn in 2020 has unfolded far more rapidly than previous credit cycle downturns. For example, it took months during the Great Recession to observe the jump in unemployment seen during the first month of the 2020 downturn. Bank loss allowances would have had to increase sharply in the first quarter of 2020, even if the loss estimates were conditioned solely on developments prior to the first quarter's end.

First-quarter 2020 allowance for credit losses

In order to better understand how changes in accounting rules and COVID-19 affected banks' estimates of credit losses, I gathered data from a sample of U.S. banks. I first identified the 39 bank holding companies (BHCs) with total assets greater than $100 billion on the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council's National Information Center page Large Holding Companies. Then 11 intermediate BHCs that are owned by a foreign bank group were dropped to focus on domestic banks.7 Also eliminated were 10 domestic BHCs for which credit risk on lending was a significantly smaller part of their business model. Relative to the remaining banks, these BHCs were less active in traditional commercial banking activities and more active in some combination of asset management, financial planning, investment banking, insurance, and securities processing.8 Data on the remaining 18 banks were obtained from the banks' first-quarter 10-Q filings with the SEC as well as their first-quarter earnings presentations and financial supplements posted on their respective websites.

The ACL for the banks in the sample increased by 65 percent from December 31, 2019, to March 31, 2020. The accounting change to CECL that took place on January 1 accounted for 50 percent of the increase in ACL (49 percent for the median bank). The remainder of the increase was due to an intentional build of ACL.

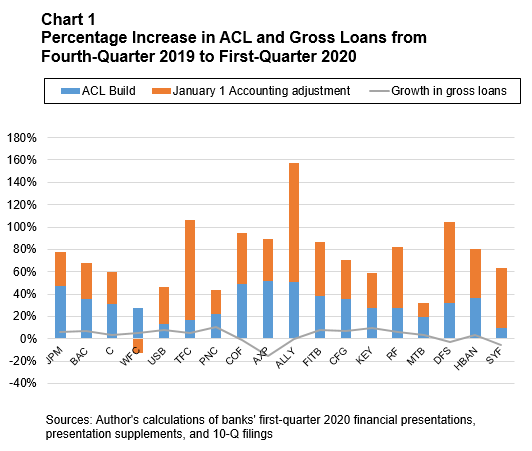

Chart 1 shows the percentage increase in ACL by banking organization (listed by their ticker symbols). The blue bar shows the portion attributable to the ACL build, and the orange bar shows the incremental contribution of the accounting change. The orange bar for WFC (Wells Fargo) is negative, indicating that the January 1 effect of the accounting change was to reduce its ACL.

Banks generally did not identify how much of the ACL build was due to COVID-19. However, chart 1 provides a crude way of getting at that issue. The gray line shows the percentage growth rate of gross loans. The allowance for loan and lease losses (ALLL) was 94 percent of the aggregate increase in ACL (94 percent for the median bank in the sample). Thus, we can use the growth rate of loans as a rough measure of the extent to which banks were increasing their credit exposure. Note that this gray line is always less than the percentage growth rate in ACL and in most cases, less than one-third the ACL build. The banks in the sample are building their ACL in anticipation of a higher loss rate on their loans, with COVID-19 likely to be the single biggest reason for the build.

As previously noted, the Federal Reserve gave the banks the option of delaying an estimate of CECL's impact on their regulatory capital ratios. The impact of CECL was estimated as the effect of the January 1 change in accounting standards on a bank's financial statement plus 25 percent of the ACL build in a quarter. All of the banks except Wells Fargo took advantage of the regulatory option of delaying an estimate of CECL's impact on their regulatory capital ratios. Wells Fargo was unable to take advantage of the option because the first-quarter impact of CECL was to raise its capital ratio.

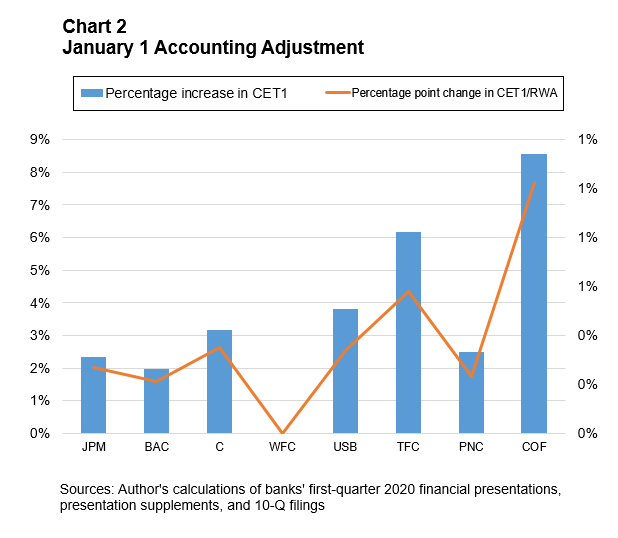

The banks in the sample provided varying degrees of detail about the impact of the CECL accounting change on their regulatory capital ratios. Fortunately, that information is available for the seven banks with more than $200 billion in total assets and is shown in chart 2. Chart 2 focuses on changes common equity tier 1 (CET1) and CET1 capital ratio, as that is the ratio for which banks supplied detailed information.

The blue bar in chart 2 is the percentage increase in the dollar value of CET1 with its scale on the left-hand side of the chart. In most cases the increase is less than 4 percent of CET1, with the biggest exception being an over 8 percent increase for COF (Capital One Financial). The orange line is the percentage point change in the CET1 capital ratio. In most cases, the increase in the ratio was 0.4 percentage points or less, with the COF again being the biggest exception. Note, however, that the banks cautioned that their reported CET1 capital ratios were estimates and subject to change. These results suggest that the delay in incorporating CECL into regulatory capital ratios will generally have a small but meaningful impact on banks' overall capital ratios.

Conclusion

Large banks' allowance for credit losses increased by approximately two-thirds in the first quarter, split about equally between an increase due to CECL and an increase due to higher expected losses. The adoption of CECL by the large banks should give investors and policymakers a clearer view of these banks' financial condition than they had at the start of the financial crisis in 2007–08. CECL would also have induced a de facto increase in capital requirements if the bank regulators had not deferred incorporating the CECL related changes in the capital requirements. The deferral was done in order to avoid creating an incentive for banks to reduce their lending during this economically stressful period. Importantly, however, this deferral merely delays a de facto increase in capital requirements; the deferral does not allow banks to reduce their loss-absorbing ability relative to what was expected at the end of 2019.

Larry D. Wall is executive director of the Center for Financial Innovation and Stability at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. The author thanks Mark Jensen for helpful comments. The view expressed here are the author's and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta or the Federal Reserve System. If you wish to comment on this post, please email atl.nftv.mailbox@atl.frb.org.

_______________________________________

1 The set consists of all domestically headquartered bank holding companies with total assets greater than $100 billion and whose business model requires they take substantial credit exposure. More detail on the set of banks is provided later in this post.

2 Using aggregate data for the set of banks in this sample, the part of the ACL dedicated to loan losses, the allowance for loan and lease losses (ALLL), is 94 percent of ACL.

3 See my earlier post "Procyclicality: CECL versus Incurred Loss Model."

4 A paper by Till Schuermann at Oliver Wyman observed that a number of financial firms were considered adequately or even well-capitalized prior to their failure, including Bear Stearns, Washington Mutual, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Lehman, and Wachovia. All of the firms experiencing runs or much higher risk premiums on their debt prior to their collapse (see the report of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission).

5 An increase in a bank's ACL will result, all else being equal, in a reduction in retained earnings. As retained earnings are a major part of regulatory capital measures, the result of an increase in ACL due to CECL would be a decrease in regulatory measures of bank capital adequacy.

6 See Kroll Bond Rating Agency's "Coronavirus (Covid-19): Why CECL Should Not Be Delayed." (Access requires the creation of a free account with Kroll.)

7 They were also dropped in part because these foreign-owned banks would report their first-quarter results at the parent level, which means they would not necessarily supply the information needed to evaluate credit allowances in their U.S. operations.

8 The domestic BHCs not included in the analysis are Goldman Sachs Group, Morgan Stanley, Bank of New York Mellon, State Street, Northern Trust, Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association, Charles Schwab, State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance, United Services Automobile Insurance, and Amerprise Financial.