As part of the Atlanta Fed's commitment to tracking COVID-19 impacts on lower- and moderate-income (LMI) people and communities, our report Navigating a Crisis: An Uneven Recovery for Communities and Organizations in the Southeast found that rental housing instability and efficiently deploying resources such as emergency rental assistance were challenges for communities across the Southeast over the course of the pandemic. In this Partners Update article, we highlight follow-up conversations about one program, the national Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) program, which is the largest COVID-related initiative that provides cash transfers to tenants or directly to landlords to rectify unpaid rent.

Key themes from the most recent conversations, outlined further in this article, include the importance of the following: 1) technology infrastructure in the implementation of ERA; 2) preexisting relationships, networks, and systems to optimize program implementation; 3) data availability and transparency; and 4) clearer guidance to mitigate the risk of fraud without hindering distribution to households in need.

About Emergency Rental Assistance

From December 2020 to March 2021, Congress allocated approximately $46 billion to fund Emergency Rental Assistance programs to aid struggling renters during the COVID-19 pandemic.1 While the US Department of the Treasury manages the program at the federal level, implementation, funds administration, and operations occur at the state and local levels.2 Local governments with more than 200,000 residents are eligible to design and administer their own rental assistance programs. States generally provide coverage to residents not residing within those eligible local areas.

Based on available data and recent reporting, state and local governments have had varied levels of success in their launch and rollout of their ERA programs. We followed up with our contacts to better understand what they saw as opportunities and challenges of the program's implementation in the Southeast.

ERA in the Southeast

Although nationwide evidence suggests that households that receive ERA funding are less likely to report negative financial (or mental health) outcomes like being behind on rent,3 ERA reporting data across the Atlanta Fed's District (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and parts of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee) suggest that households in southeastern states may have received less financial support relative to national peers.

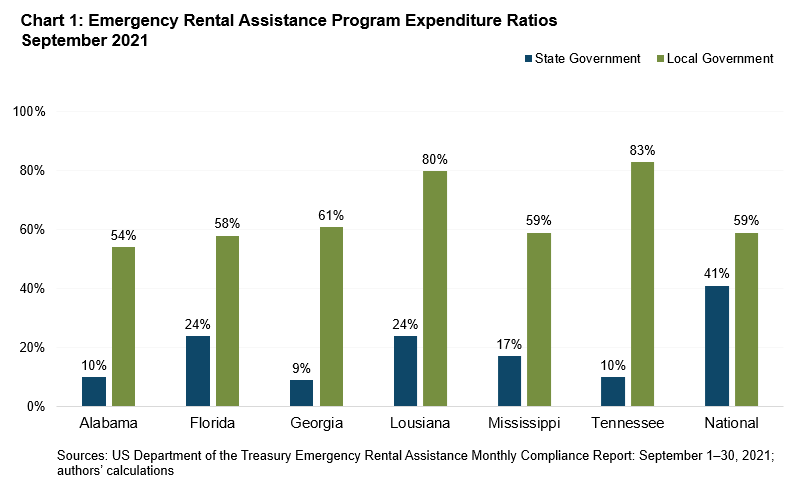

In September 2021, the first full month of data available following the US Supreme Court's overturning of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's national eviction moratorium, Treasury data revealed that state-run ERA programs across the Atlanta Fed's District were only able to reach expenditure ratios of from 9 percent to 24 percent (see chart 1), while the nationwide expenditure ratio amounted to 41 percent.4 Expenditure ratios are calculated as the sum of expenditure for assistance to households to date divided by 90 percent of the ERA1 allocation. The additional 10 percent accounts for administrative costs. Some southeastern states' combined local funds, however, outperformed state programs with expenditure ratios that ranged from 54 percent to 83 percent.5 As of September 30, 2021, state and local programs with expenditure ratios of less than 30 percent were determined to have "excess funds" that were subject to later reallocation to other programs. Programs that had not obligated at least 65 percent of funds were required to submit a program improvement plan.6

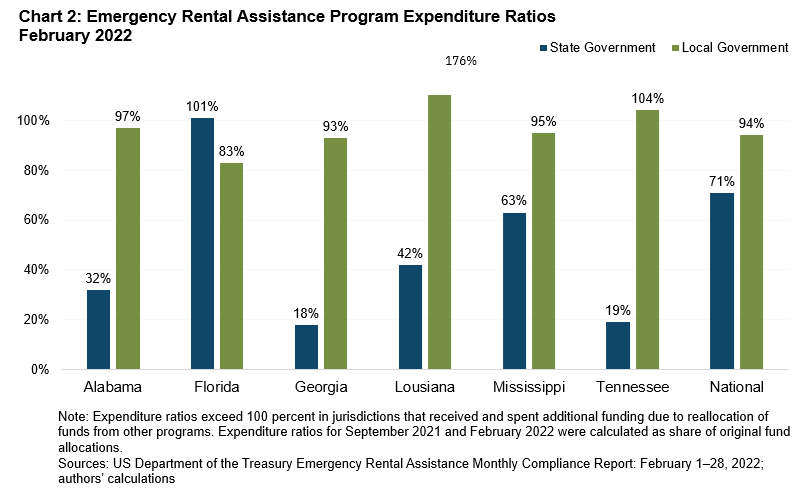

Although improvements were made, by February 2022, when we began to speak with southeastern contacts close to the programs, many state ERA programs across the Atlanta Fed territory continued to lag national program expenditures, particularly Georgia and Tennessee, which lagged 52‒53 percentage points behind national peers (see chart 2).

These data, including the juxtaposition of underutilized state-wide funding and greater utilization of local funding, warranted more examination. Accordingly, the Atlanta Fed Community and Economic Development team spoke with 17 southeastern affordable rental housing stakeholders from a convenience sample to understand more about local and state ERA implementation across the District. The intent of the conversations was to understand what made some programs better able to reach struggling renters than others, understand bottlenecks, and document best practices. The stakeholders we interviewed were chosen to include state and local administrators of ERA (which includes public and community-based organizations) and individuals representing both tenants and landlords across the District's six southeastern states. A smaller team coded data from the interviews and synthesized the trends.

Although the sample was not statistically significant or fully representative of all ERA programs in the Southeast, the themes outlined may be useful for further research and analysis and to inform development of similar programs in the future. We gleaned several key high-level themes from our semi-structured interviews, these key takeaways:

- Technology and infrastructure: Interviewees spoke often about technology infrastructure and the implementation of ERA—both in terms of challenges and assets. Web-based platforms created opportunities and issues, depending on the program and population served. For example, broadband access was a repeated concern, especially in more rural areas. Contacts cited examples of targeted outreach to hard-to-reach populations (such as rural communities, households without broadband connectivity, and the underemployed) and on-site support for applicants in filling out their online applications.

- Networks: There were frequent mentions of how preexisting relationships, networks, and assistance delivery systems could help or impede program growth and implementation. For example, utilizing existing networks that support natural disaster recovery to administer ERA funding was a best practice mentioned by several contacts.

- Data: Many interviewees, both state and local program administrators, expressed a lack of data availability on ERA disbursement at the household level and desire for better data and information transparency. Examples of what ERA stakeholders suggested include better data on the availability and affordability of existing housing stock, more transparency on where program funds were disbursed, detailed demographic information on applications and disbursements, more transparency on the pipeline of applications, and statistics on reasons for denial of an application.

- Fear of fraud: Several contacts noted that there are mixed perceptions of fraud concern from program administrators on ERA disbursement. Future programs may consider including clearer guidance from the grantor on program oversight that may bolster the efficiency and effectiveness of funds reaching households eligible for ERA support.

Moving forward

As the continuing impacts of COVID-19 and other shocks on the economy unfold for LMI communities, the Atlanta Fed's Community and Economic Development program will continue to work with policymakers, practitioners, funders, and researchers to advance the lessons and highlight the issues around programs like the ERA that were designed to help communities weather the pandemic-related economic downturn.

The CED team at the Atlanta Fed supports efforts that promote community development and advance economic mobility and resilience in communities. If you would like to learn more or have questions, please contact Sarah Stein at sarah.stein@atl.frb.org or Dontá Council at donta.council@atl.frb.org.

By Sarah Stein, CED adviser, Dontá Council, CED adviser, and Grace Meagher, CED research analyst I. A team comprised of Ann Carpenter, Dontá Council, Mary Hirt, David Jackson, Grace Meagher, Sarah Stein, and Charlene van Dijk—all part of the Community and Economic Development program at the Atlanta Fed—designed the interview protocol and conducted the interviews. The authors thank the team and the interview subjects who generously gave their time. The views express here are the authors' and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors are the authors' responsibility.

_______________________________________

1 The Emergency Rental Assistance program is a federal program that makes funding available to assist households that are unable to pay rent or utilities. This program was funded under two separate legislative acts, ERA1 and ERA2. ERA1 was funded at $25 billion under the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021, which was enacted on December 27, 2020. ERA2 was funded at $21.55 billion under the American Rescue Act of 2020, which was enacted on March 11, 2021.

2 US Department of the Treasury. Emergency Rental Assistance Program Allocations and Payments.

3 Airgood-Obrycki, Whitney. June 14, 2022. The Short-Term Benefits of Emergency Rental Assistance. Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies.

4 US Department of the Treasury. Emergency Rental Assistance Program Reporting.

5 Ibid.

6 US Department of the Treasury, October 4, 2021. "How Emergency Rental Assistance Reallocation Works."