A mural depicting jazz legend Ella Fitzgerald at Lorene's Fish House in the Deuces neighborhood of south St. Petersburg, Florida. Photo by Ted Pio Roda

On a muggy July morning in St. Petersburg, Florida, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta president Raphael Bostic joined a couple dozen people in an unadorned space that once was the produce department of a Publix Super Market.

Far from the Reserve Bank's stately headquarters, Bostic and other Atlanta Fed officials mostly listened as community leaders opined on the state of inclusive economic growth in the Gulf Coast city of 260,000. Situated on a peninsula about six miles from Tampa across Old Tampa Bay, St. Pete maintains an identity distinct from its larger neighbor. Its palm-shaded core mixes sleek modern structures such as the striking Salvador Dali Museum with bungalows and remnants of old Florida, like walking mail carriers and the Sundaze Motel.

For all its charm, like most cities St. Pete has work to do to spread prosperity across its demography and geography, which is a major reason the city is launching an ambitious plan to redevelop its 22nd Street corridor, known as "the Deuces," and the Gas Plant District, a historic Black neighborhood gutted by construction of Interstate 275 in the early 1970s and a domed stadium in the late '80s. Tropicana Field is home of Major League Baseball's Tampa Bay Rays, but the dome was built years before the city had a team. The stadium plan materialized after a failed idea to develop an industrial park on the site.

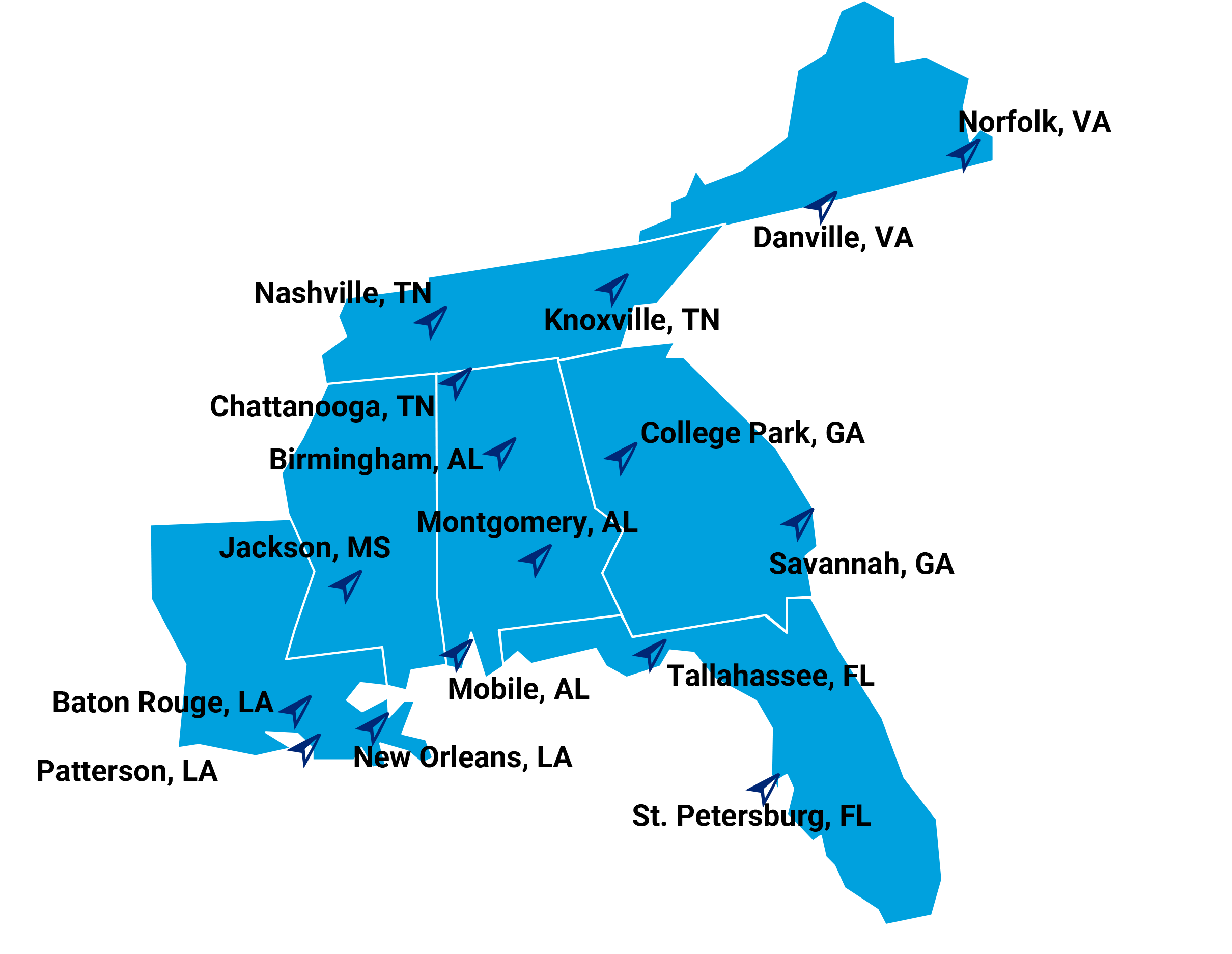

The central bank team visited St. Petersburg in part because it is among 16 participants in the Southern Cities Economic Inclusion initiative, a program sponsored by the National League of Cities, the Kellogg and Annie E. Casey foundations, and the Atlanta Fed. The initiative is among the first to showcase the Reserve Bank's Community and Economic Development (CED) department's engagement unit. That group takes Fed research, data, and expertise directly to communities to use in real-world programs. Its mission positions the two-year-old engagement team as a key element in animating the Atlanta Fed's strategic priority to promote economic mobility and resilience.

St. Pete began its community redevelopment plan before the Southern Cities initiative began, but the project is an ideal opportunity for initiative backers to support a major effort to boost economic inclusion and to take lessons from St. Pete's work that other cities might apply. The Southern Cities initiative is designed to help midsized cities in the region learn from one another what's working, and what's not, in trying to spread economic growth and prosperity, particularly to historically underserved Black businesses and communities. David Jackson, head of the Atlanta Fed's CED engagement group, said research and frontline experience show municipal leaders in the South are more apt to embrace ideas from peers in the region than from cities elsewhere.

"The idea behind the Southern Cities Economic Inclusion initiative is we are a

sort of clearinghouse for data and information. So, we might say, St. Pete,

you may want to talk to the people in Knoxville. Hey, Knoxville, you may want

to talk to people in St. Pete."

— David Jackson, Atlanta Fed CED engagement group

David Jackson. Photo by Ted Pio Roda

"The idea behind the Southern Cities Economic Inclusion initiative is we are a sort of clearinghouse for data and information," Jackson said. "So, we might say, 'St. Pete, you may want to talk to the people in Knoxville. Hey, Knoxville, you may want to talk to people in St. Pete.'" (Knoxville is another of the initiative's participant communities. See a complete list and background on the initiative.)

Ultimately, the aim is to bring together southern cities, develop southern strategies, and highlight southern successes to improve economic mobility and resilience in the region. The National League of Cities conceived the initiative to help cities devise and implement strategies to close racial disparities in economic outcomes and expand opportunities for residents and businesses of color. A particular focus of the initiative is helping cities craft programs to channel contracts toward women- and minority-owned firms and devise ways to provide incentives to larger firms to award business to local women and minority vendors.

In the initiative, mayors and city administrators from the various cities will spend two years building relationships. At the same time, Jackson explained, the Atlanta Fed will visit several of the participating cities and determine how to apply Reserve Bank research and convening power—the ability to gather experts—directly to projects like St. Pete's redevelopment program.

In several meetings with policymakers from the 16 cities, Jackson and senior CED adviser Charlene van Dijk have shared Atlanta Fed resources including the Small Business Credit Survey, the Small Businesses of Color Recovery Guide, and tools from the Reserve Bank's Advancing Careers for Low-Income Families initiative. The exchanges with Fed experts and counterparts from other cities can broaden the perspective of St. Pete officials, said Doyle Walsh, senior adviser to Mayor Ken Welch.

The Atlanta Fed's Charlene van Dijk. Photo by Ted Pio Roda

The Atlanta Fed's Charlene van Dijk. Photo by Ted Pio Roda

Cities in the inclusion initiative will partner with the Atlanta Fed on the next installment of the Federal Reserve's Small Business Credit Survey, a detailed nationwide report on the health of small companies. Working on the survey will offer local policymakers a rich pool of data and anecdotal information they can use to better understand the experiences of businesspeople in their own communities, Walsh pointed out. Officials may be intimately familiar with their own small business community, but the survey will allow them to compare how, for example, revenue and employment at those firms held up through the pandemic relative to businesses across the region and the country.

"This is an opportunity to reach small businesses that are underrepresented, and it will provide insight into how local businesses are faring in today's economy," Walsh said.

In some cases, van Dijk said, city officials can expand their vision simply by learning how counterparts elsewhere approached a project. For instance, when resources are scarce, rather than building a costly recreation center, perhaps developing less-expensive green space would improve health and well-being just as much while satisfying constituencies that might not have supported building a recreation center.

"The idea," said Jackson, "is not that the Fed is going to come in with definitive answers, but we do have research that illuminates potential answers. And we have friends who do this work. You know, just as important as pointing out what works is stopping places from doing stuff we know does not work." An approach that often does not work is carrying out elaborate plans without much input from those who will be directly affected or constructing infrastructure without a careful plan to ensure the surrounding community benefits. As Jackson points out, everyone enjoys shiny new objects, and they are not inherently bad. But context is critical.

"Are you creating jobs for the people who live there, jobs that pay family-supporting wages? Are you structuring requests for proposal and other plans to incentivize contracts to go to qualified minority and women-owned businesses?" he said. "Those are critical questions to ask up front."

Blunt feedback comes from caring and passion

In St. Pete, the big revitalization project aims to transform what's officially called the South St. Petersburg Community Redevelopment Area, which is home to about 37,000 people. During a bus tour, Atlanta Fed visitors see plenty of hopeful signs. A gritty warehouse arts district is maturing, boosted by the city's vibrant arts community. Bike and pedestrian paths thread throughout the redevelopment area. Plans call for affordable housing, including studio space for artists, parks, an incubator for creative and tech-oriented startups, event halls, and shared working spaces. A Healthy Corner Store Initiative aims to help existing businesses bring fresh produce to the neighborhood.

Uncertainties, like a global pandemic, have complicated St.

Petersburg’s redevelopment plans. Photo by Ted Pio Roda

Uncertainties, like a global pandemic, have complicated St.

Petersburg’s redevelopment plans. Photo by Ted Pio Roda

However, Atlanta Fed officials saw both potential promise as well as

concrete evidence of the challenges that confront sweeping redevelopment

efforts. For example, the Healthy Corner Store Initiative will seek to

improve several census tracts surrounding 22nd Street that are classified by

the US Department of Agriculture as

"low income and low access"

to healthy food—food deserts. In that same area, two supermarkets have

closed in a shopping center now owned by the city. Most recently, a Walmart

Neighborhood Market shuttered in 2017.

Along with ample energy and optimism, Bostic, Jackson, and van Dijk also heard disillusionment from community leaders who have seen well-intentioned plans wither before. In the meeting at the converted Publix, a longtime community advocate said he is rooting for the redevelopment to succeed but expressed exhaustion from repeated "loud talk saying nothing." Another said the Gas Plant District, in particular, has endured "a long trail of broken promises."

While hope is essential for these kinds of projects to succeed, blunt feedback is valuable, Bostic explained, to fully appreciate the context on the ground. "One of the things I appreciate about visiting communities," he said, "is they all tell us exactly what they think because it comes from a place of caring and passion."

Redevelopment is a long arc

Inclusive economic development requires much to go right. And it might not always be immediately obvious whether you do get it right.

It requires planning, persistence, and perseverance. An undertaking like the St. Pete community redevelopment is complex and expensive in the best of circumstances. Uncertainties like a global pandemic, a worsening shortage of affordable housing, and the expiration of the Rays' lease on Tropicana Field in 2027 only add complications. In fact, citing changed circumstances, the city in late June announced it is reworking a 2017 master plan for the redevelopment of the Gas Plant district.

It's clear St. Pete's work will not bear immediate fruit. Revitalizing a seven-square-mile section of a city is a long-term commitment. Hence, Bostic stressed the importance of staying power, in part because bold projects that require significant capital and imagination often founder on the vagaries of election cycles that shape and disrupt public policy.

A longtime researcher of urban development, Bostic noted that agendas change with turnover among mayors and city councils. By contrast, sweeping efforts like St. Pete's revitalization proceed along "a 20-year arc," Bostic said. "It's not a four-year arc. It's not an eight-year arc."

Through knowledge sharing and other support, the Fed can help to bridge those two- and four-year time frames, he said, and thus help sustain momentum. In fact, Jackson had visited St. Pete three times as of early September, and he and van Dijk will bring a team of Fed experts to the city again this winter.

"We're not going to leave," Bostic said at the converted Publix, which serves as headquarters of the Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg, Florida's largest philanthropy devoted to racial equity. "The whole point of what we're doing here is we are trying to do something different. I doubt you've had conversations with the Fed in the past where we're actually talking about doing things."

What he and Fed officials aim to do is improve communities by, in the Atlanta Fed's parlance, making the economy work for everyone. The better communities work, the easier it is to make monetary policy because the economy is stronger and more resilient, Bostic said. Thus, community development is firmly situated within the central bank's core duties of striving for maximum sustainable employment and price stability.

The Southern Cities initiative aims to bring additional intellectual energy to deep-seated challenges in St. Pete and places across the Southeast. The Atlanta Fed hopes to help that happen. "As a southern-based institution, we are proud to be part of an effort that helps national institutions invest and partner with southern cities to build networks of leaders from across the region," Bostic said. "We all realize the Southeast has considerable economic challenges. But we have vast opportunities because people across the region are deeply committed to the places they live and, like the Atlanta Fed, want to achieve an economy that works for everyone."