Raphael Bostic

President and Chief Executive Officer

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

Atlanta Business Chronicle 2024 Economic Outlook

Atlanta, Georgia

January 18, 2024

Key Points

- On January 18, Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic discusses his latest thoughts on the macroeconomy and monetary policy at the Atlanta Business Chronicle's 2024 Economic Outlook event.

- Bostic says the Federal Open Market Committee may be approaching a new phase in the monetary policy cycle that began in March 2022.

- In Bostic's view, monetary policy is sufficiently restrictive to promote the return of inflation to the Committee's 2 percent target over the medium term.

- The Committee's primary challenge, Bostic says, now shifts to assessing how long the federal funds target range should be held at its current level before it will be appropriate to begin unwinding the restrictive stance of policy.

- Bostic explains that faster-than-expected progress on inflation, strong economic growth, and a healthy labor market signal it may soon be time to reassess the monetary policy stance.

- Bostic sums up his current policy views with two words: grateful and vigilant. He's grateful for the progress on inflation. But he's staying vigilant because, though inflation has been moving toward 2 percent for some time, numerous risks could throw it off course.

- Bostic affirms that his views will be informed by incoming data, and should conditions evolve differently from his expectation, he is willing to adjust based on what happens.

Good afternoon. As many of you probably noted, the title of my talk today is an homage to the Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King Jr. as we conclude the week when the nation honors his legacy.

It's a privilege to be with you. I'd like to especially thank publisher David Rubinger and the staff at the Atlanta Business Chronicle for hosting this event. I spend a good deal of time with journalists and the press more generally, but I don't say often enough that I believe they do our community and our country a service. Informed consumers and business leaders make better decisions, and that in turn improves the efficacy of monetary policy and the workings of our economy. So, thanks to you all.

Today, I will discuss my latest thinking on the macroeconomy and monetary policy, this time in my capacity as a voting member of the Federal Reserve's policymaking Federal Open Market Committee. The Atlanta Fed president votes every three years, and 2024 is my turn.

Before I go further, though, let me remind you that the thoughts I'll share are mine alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of my colleagues on the Committee or at the Atlanta Fed.

As we enter a new year, we may be approaching a new phase in the monetary policy cycle that began in March 2022. Then, the Committee initiated a series of moves that raised the federal funds rate from effectively zero to a range of 5 1/4 to 5 1/2 percent, as we took action to subdue a bout of inflation born of pandemic-induced economic imbalances. Where are we now in this fight?

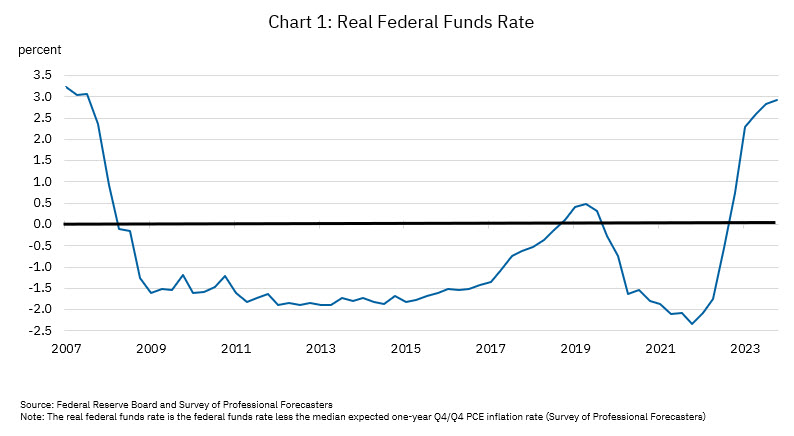

This slide illustrates that the real federal funds rate—that is, our interest rate adjusted for inflation—is at its highest level in over a decade (chart 1). To summarize one key takeaway for you, my view today is that monetary policy is at an appropriately restrictive stance, sufficient to promote the return of inflation to our 2 percent target over the medium term.

For me, the primary challenge now shifts to assessing how long the federal funds target range should be held at its current level before it will be appropriate to begin unwinding the restrictive stance of policy.

In forming this judgment, the Committee must gauge the long and variable lags of monetary policy—that is, how much bite from restrictive policy remains to play out—in determining the path for normalizing the federal funds rate that will be consistent with achieving the dual mandate Congress has given us. As a reminder, our charge is to return inflation to our target of 2 percent over time while supporting the strongest possible pace of employment growth.

You have no doubt heard the goal of getting inflation to 2 percent while experiencing limited or no employment loss described in the popular press as a "soft landing." While I generally avoid using this term, as it doesn't really have a clear definition, whether one calls this dynamic a "soft landing," "the golden path," "immaculate disinflation," or something else, the fact is that it is quite rare and awfully hard to achieve.

But so far, so good. Probably the clearest illustration of our progress is this: when the Committee began increasing the federal funds rate in March 2022, the headline unemployment rate was 3.6 percent. It was 3.7 percent last month. So, the Committee has undertaken one of the most aggressive policy-tightening campaigns in recent Fed history without significant damage to the labor market. That is highly unusual.

While that progress is encouraging, I want to stress two things. First, we are still a ways from our 2 percent target. Second, there remains considerable uncertainty about how supply and demand in the economy will evolve in 2024 as we seek to promote a return to balance of these two fundamental forces.

Inflation rate declining faster than expected

Let me offer context for my policy views. Over the past year, many of the key data points I monitor have moved more rapidly than my team and I, along with most forecasters, expected. In large part, that is why we may be approaching the time to consider removing restriction from our policy.

What are these fast-moving indicators?

Start with overall economic activity. In the early and middle parts of 2023, most economic observers, including economists at the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, predicted that tight financial conditions would contribute to a mild recession in late 2023 followed by a moderately paced recovery. We at the Atlanta Fed were a tad more optimistic. At the start of 2023, rather than seeing a recession, our staff projected gross domestic product (GDP) growth of about 1 percent for the year.

Well, the US economy proved to be even more vigorous than our more optimistic outlook. We subsequently bumped the forecast up to about 2.1 percent in September, and we are now expecting GDP growth to come in at 2.6 to 2.7 percent for the year. We'll get the first estimate in a week.

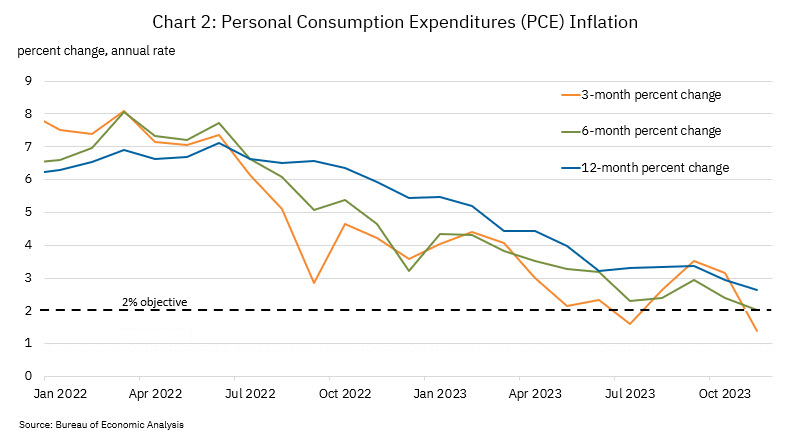

Inflation has similarly surprised us to the good (chart 2).

In June of last year, we forecast that year-end 2023 inflation, as measured by the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index, the Committee's preferred metric, would be around 3.5 percent. Late last year, we lowered our forecast to 2.9 percent.

Well, the latest print has PCE inflation at 2.6 percent for the 12 months through November. (The US Bureau of Economic Analysis will release PCE inflation for December next week.)

Taken together, these data indicate that the golden path of declining inflation and still-solid labor markets and economic growth may stretch farther than most of us figured just a few months ago.

Because I'm data dependent, I have incorporated the unexpected progress on inflation and economic activity into my outlook, and thus moved up my projected time to begin normalizing the federal funds rate to the third quarter of this year from the fourth quarter.

On balance, it appears that restrictive monetary policy is indeed working to help lower the rate of inflation. The rub is that if we keep policy too restrictive for too long, we risk doing unnecessary damage to the labor market and the macroeconomy.

Here, I think it is worth considering what my staff and I call "passive tightening." Basically, this means that as the inflation rate declines, and the federal funds rate holds steady, policy in effect becomes tighter.

Put another way, to borrow an analogy from my friend Austan Goolsbee at the Chicago Fed, this phase of policymaking is a bit like cooking a holiday turkey. You clearly need heat to cook the turkey. But everyone in this room knows that one faces the risk of overcooking the turkey by leaving it in at full baking heat for too long, because the turkey continues to cook even after it is removed from the oven. You have to take the bird out before it is fully done or we get a dry holiday meal.

Likewise, the effects of restrictive monetary policy could continue to impinge on economic activity and labor markets even after the Committee stops actively tightening. Therefore, we must seek a delicate balance, and the time to seriously ponder how we arrive at that balance will quite likely soon be at hand if it is not already.

If we wait too long to begin adjusting policy, we run the risk of overtightening the economy and serving up a labor market so weak that it unsettles the economic lives of more American families and businesses than necessary to get inflation back to our 2 percent target. So, our task now is to assess the economy's progress and decide when it is time to start easing our restrictive policy stance.

What am I watching?

Let me list a few metrics that will be of particular interest to me in assessing the appropriate path for policy in coming months.

First, I will be looking at shorter-term inflation measures for clues to where the 12-month inflation readings are likely headed. As the chart shows, the six-month and three-month change in the PCE inflation gauge, respectively, were right at and a bit below the 2 percent target as of November (chart 2). I will look for continued good news there.

Next, labor market indicators will offer important signals about whether we remain decisively on the path to 2 percent inflation without serious damage to employment.

After surging in 2022 as labor demand dramatically outstripped supply, nominal wage growth is easing back toward the average annual rate of just over 3 percent that prevailed in the three years before the pandemic. Meanwhile, inflation has decelerated faster than nominal wage growth, so real inflation-adjusted wage increases nudged into positive territory in mid-2023 and are still climbing.

However, real average hourly earnings remain below pre-COVID levels. So, a bit more acceleration in real wages should not necessarily spark a resurgence in inflation. In short, a normalization of real wage growth back to prepandemic levels would be conducive to reaching the inflation objective without tanking the economy, and by and large that's what we're seeing.

Finally, I'm tracking job growth and job losses.

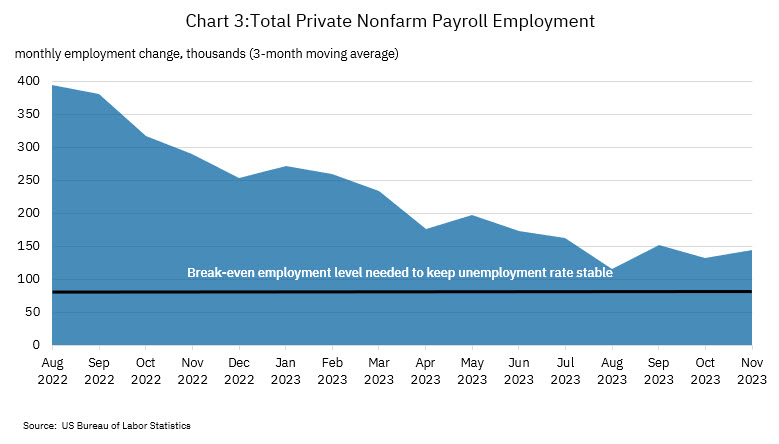

For now, the labor market remains broadly healthy—remarkably so during a forceful monetary policy tightening cycle. Even as employment growth has slowed over the past year, the economy is still adding enough jobs each month to hold the unemployment rate stable at historically low levels. And as my staff and I talk to business leaders, we hear very few say they expect layoffs.

At the same time, employment growth is slowing (chart 3). It would be slowing even more sharply but for one comparatively small employment sector: health care and social assistance.

Jobs in health care and social assistance, the bulk of which are in health care, account for only 14 percent of private-sector employment. Yet that single sector generated about 60 percent of private-sector job growth over the past seven months. In fact, without health care and social assistance, employment growth over the past several months would be below the level needed to keep the unemployment rate from rising.

If employment growth slows more rapidly, then that would complicate the task of continuing to promote disinflation alongside healthy economic activity. In that case, I would need to adjust my view of the appropriate path for policy.

Uncertainty abounds

Of course, in the coming months none of this—continued disinflation, normalizing wage growth, a healthy labor market—is assured. We remain in a highly uncertain economic environment.

Recall the continual shifts in the outlook for inflation and GDP growth I mentioned a moment ago. Those changes demonstrate just how difficult it remains to discern true signals from noise in this economy.

That's because uncertainty lurks in numerous corners. Conflicts around the world could again complicate global supply chains and rattle energy markets. Other geopolitical events including federal budget fights and elections at home and abroad could affect economic activity and financial markets. A weakening labor market could sap consumer spending that has buoyed GDP growth.

In light of these risks, it probably should not be surprising that our Survey of Business Uncertainty continues to find executives are more unsure of future sales and employment growth than they were before the pandemic.

In such an unpredictable environment, it would be unwise to lock in an emphatic approach to monetary policy. That is why I believe we should allow events to continue to unfold before beginning the process of normalizing policy.

As always, my views will be informed by incoming data, and I will remain steadfast in my commitment to achieving the 2 percent inflation objective. Should conditions evolve differently from my expectation, I am willing to adjust my view of policy based on what happens. Should underlying economic momentum prove stronger than expected and spark inflationary pressure, the Committee may need to maintain the restrictive policy stance longer than I foresee. Relatedly, premature rate cuts could unleash a surge in demand that could initiate upward pressure on prices.

This argues for caution to ensure that we don't undermine the great progress we have made to date in bringing inflation back to target. But it also calls for heeding the data and being responsive in our plan to normalize policy. Even after incorporating the recent softness in the underlying inflation data, my baseline forecast for full-year core PCE inflation is still 2.4 percent. That said, if we continue to see a further accumulation of downside surprises in the data, it's possible for me to get comfortable enough to advocate normalization sooner than the third quarter. But the evidence would need to be convincing.

During the pandemic, I've tried to use a few terms to characterize my approach to policy in the moment. Summarizing all that I've said today, those words would be grateful and vigilant. I'm very grateful for the progress that has been made to date in the fight against inflation. But I'm staying vigilant because, though inflation has been on a path toward the 2 percent target for some time, there are risks that could throw it off course.

To be sure, striking the delicate balance of price stability without undue harm to labor markets will be exceedingly difficult. It's rarely been done following a serious bout of inflation. But that's the job, and we are going to continue to do everything we can to achieve it.