Raphael Bostic

President and Chief Executive Officer

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

Atlanta Economics Club

Atlanta, Georgia

November 12, 2025

Key Points

- Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta president and CEO Raphael Bostic discusses his outlook for the macroeconomy and monetary policy at the monthly meeting of the Atlanta Economics Club on November 12.

- He acknowledges that Fed officials are formulating policy without some data they typically rely on because of the federal government shutdown. But Bostic assures that Fed policymakers are not flying blind, as they have numerous data sources outside the federal government.

- Bostic says the Federal Reserve's two mandated objectives, price stability and sustained maximum employment, are both under pressure. Inflation remains above the Committee's 2 percent target, where it's been for nearly five years. Meanwhile, the labor market is shifting as monthly employment growth and labor supply growth have slowed.

- Policymakers face delicate trade-offs because the prescriptions for reducing inflation risk increasing unemployment, and the moves that typically boost employment risk stoking inflation.

- Bostic says price stability remains the more pressing risk. Signals from the labor market, he explains, don't indicate a cyclical downturn clearly enough to merit significant policy loosening while inflation remains well above target.

- He cautions that surveys and other forward-looking indicators suggest inflation is unlikely to decline substantially for some time. That raises the concern that inflation expectations could drift upward and trigger behaviors which produce higher actual inflation.

Thank you for inviting me to be with you. I especially enjoyed the short trip to the venue.

At the Atlanta Fed, we are honored to serve as regular host to the Atlanta Economics Club monthly meetings. My staff and I appreciate the work you do to advance the understanding and practice of economics.

Before I dive into my remarks, let me remind you that these thoughts are mine and do not necessarily reflect the views of my colleagues on the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) or at the Atlanta Fed.

Today, I will detail my economic and monetary policy outlook through the lens of the objectives Congress assigned the Federal Reserve: price stability and sustainable maximum employment. Let me set the stage by sharing that I believe that risks to both of the mandated objectives make this the most challenging environment since I became a central banker in 2017.

In this moment, we face the difficult circumstances of softening labor market conditions while inflation remains materially above the FOMC's stated 2 percent objective. The unwelcome implication is that reductions in interest rates that normally would mitigate risks to the employment mandate could heighten the risks to the price stability mandate. And vice versa: maintaining moderately restrictive monetary policy, the typical tool in battling inflation, raises the risks to the employment mandate.

The job of an FOMC participant is to confront this tension and weigh the trade-offs inherent in determining the appropriate setting for monetary policy. Right now, it is an extremely close call. But I'm going to detail my case that, despite shifts in the labor market, the clearer and urgent risk is still price stability.

Let me preface the meat of my talk by noting that we've missed some data releases because of the federal government shutdown. We are not flying blind, however, and I'll discuss some of the alternative information sources guiding my policy thinking right now.

Elevated inflation likely to persist

Let's dig into the price stability mandate first.

For much of this year, commentary about the direction of inflation has focused on how changes in trade policy—and most notably tariffs—will affect prices. That remains a critical question, and I'll explore it in detail shortly.

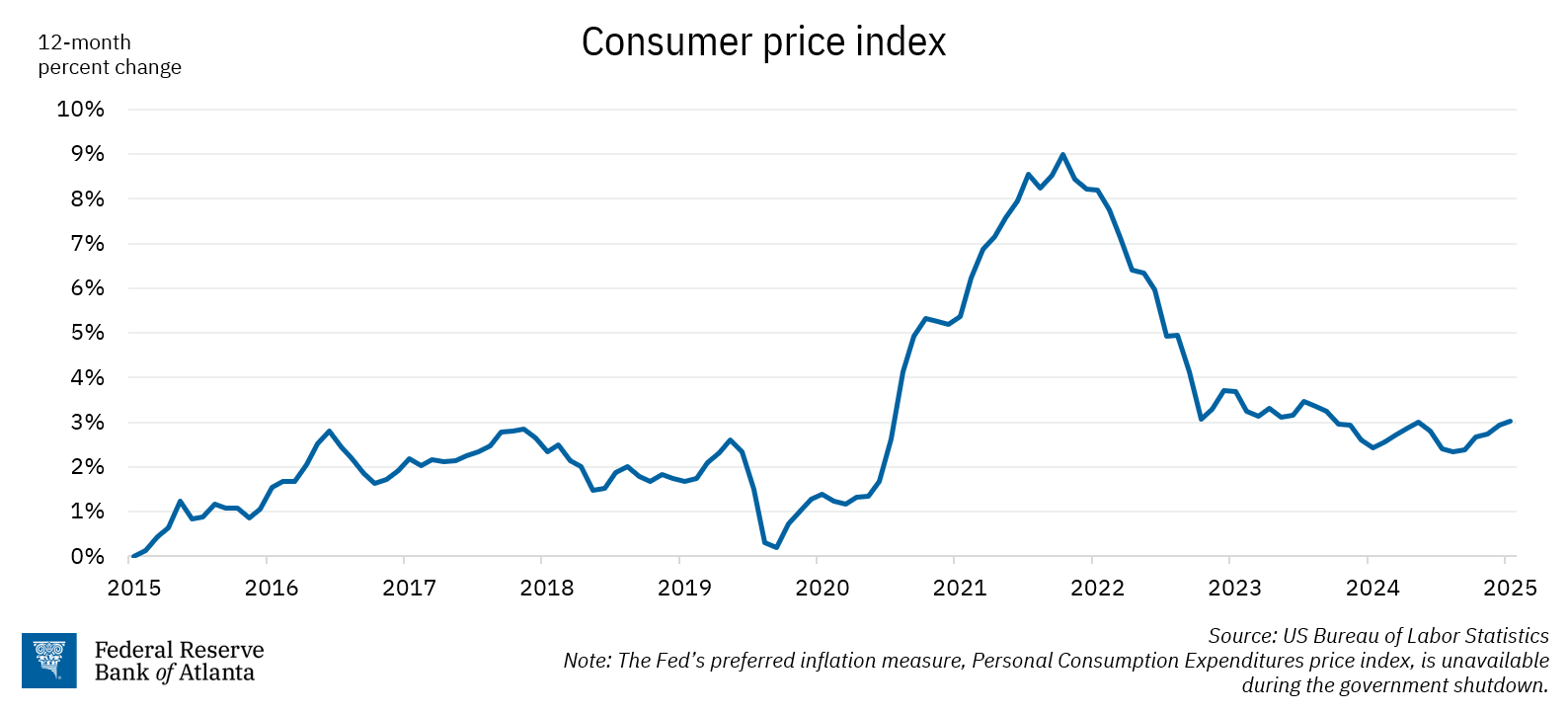

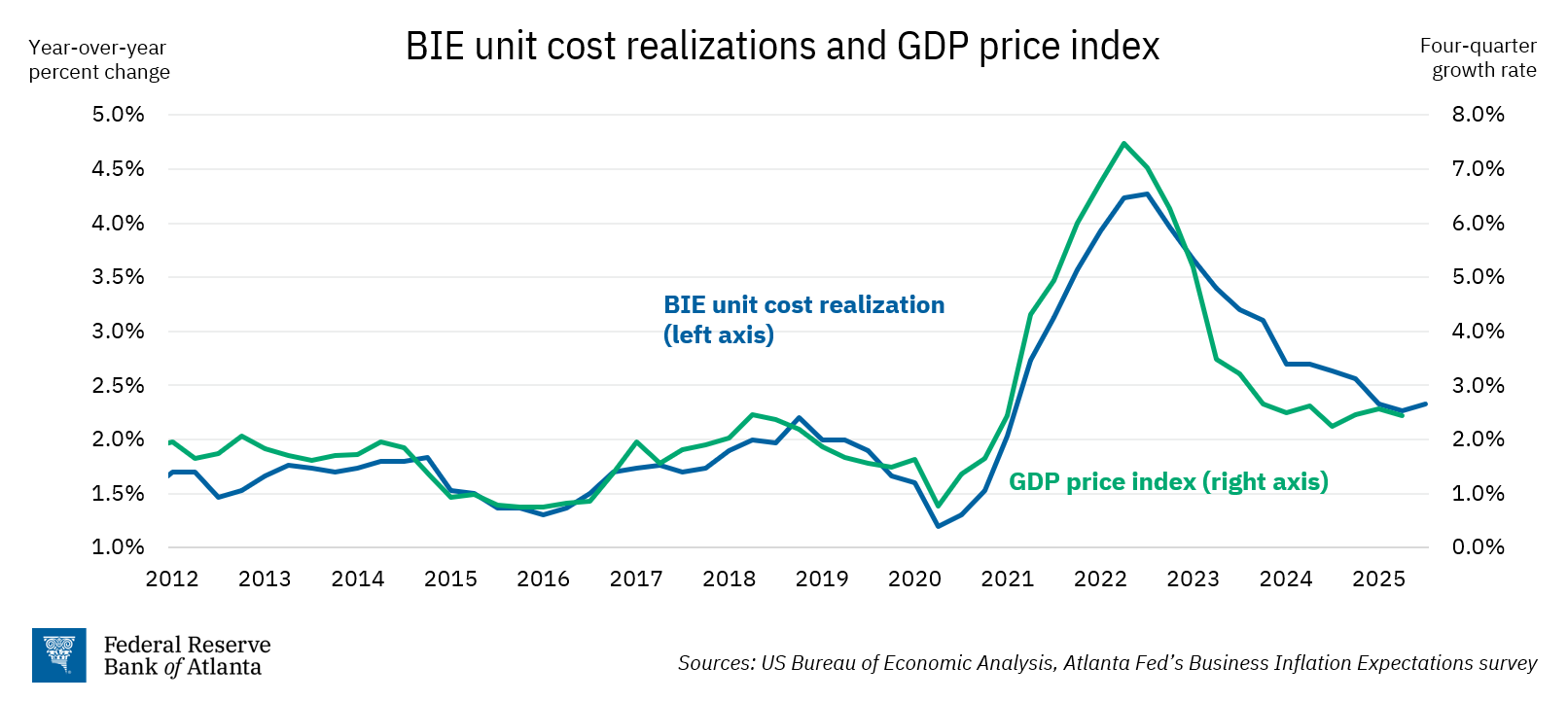

Before I do that, though, it's important to remember that inflation has already exceeded the Committee's 2 percent target for nearly five years. (Chart 1) The latest reading on the consumer price index (CPI), the well-known alternative to the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index that is the basis of the 2 percent inflation objective, strongly suggests that PCE inflation would be telling us we remained well above target in September—if we had the actual PCE data in hand. The CPI print for September was 3 percent, which equates to about 2.7 percent in the PCE.

Chart 1

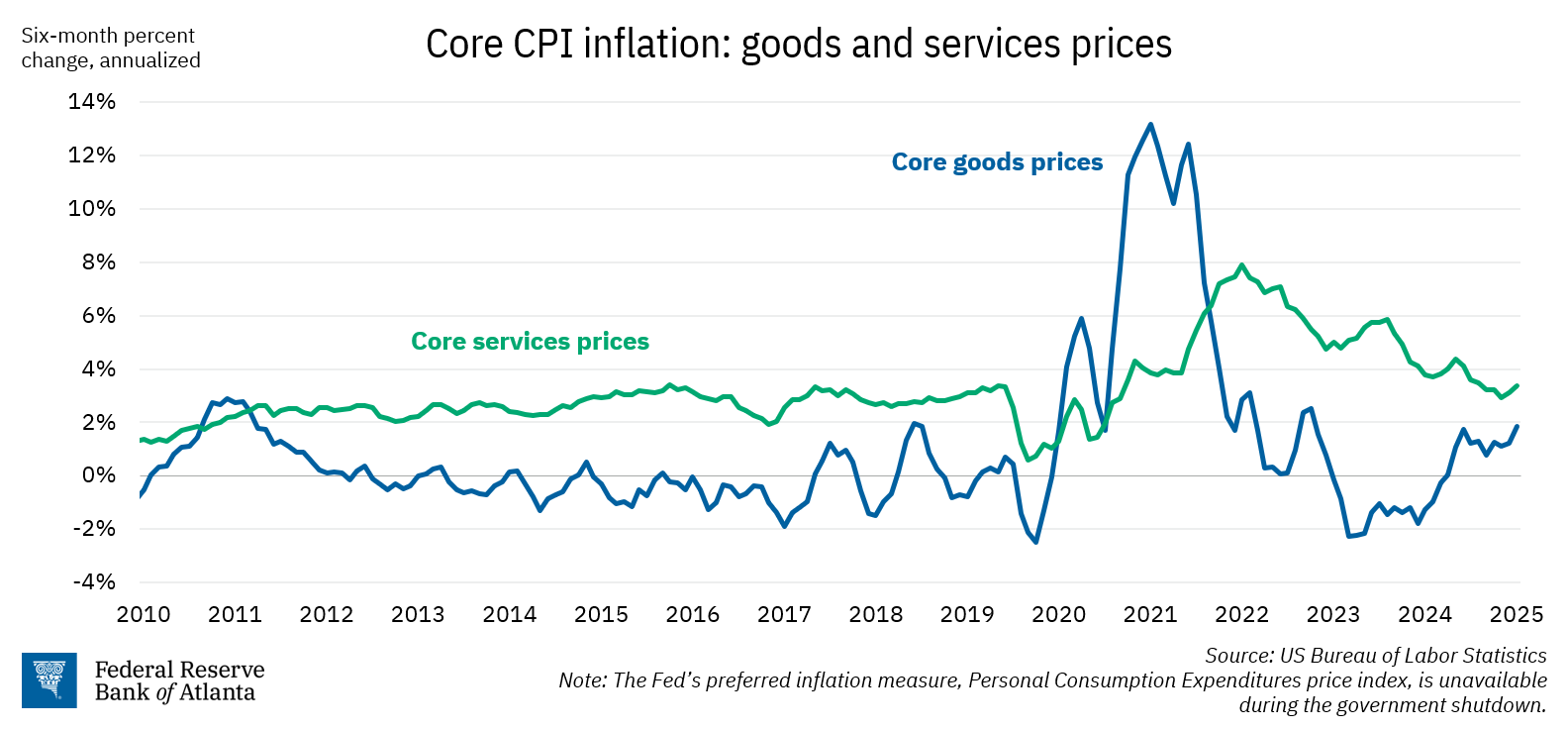

So far, we have not seen tariffs cause a severe spike in inflation, but they have played a role in buoying prices. This next slide (chart 2) illustrates why inflation is still too high, in a nutshell. As you see, core services prices, those excluding energy services, have defied most forecasters' expectations and remained above prepandemic levels. Then in the spring, core goods prices began climbing as tariffs kicked in. So, the main contributors to elevated inflation are now services prices other than housing—"supercore" services—and core goods prices. That is a reversal from 2024, when significant price pressures came from the shelter category and core goods prices were actually declining.

Chart 2

To cut to the chase, based on the (admittedly less than fulsome) data in hand and a host of forward-looking indicators, I see little to suggest that price pressures will dissipate before mid- to late 2026, at the earliest. Now, without all the usual inflation data, you may reasonably wonder how I've formed such a strong view of where things stand via price stability.

The answer is that in coming to this view, I'm leaning heavily on information from our Bank's Economic Survey Research Center. That team conducts three primary surveys of business leaders across the country: the Business Inflation Expectations (BIE) survey, the CFO Survey in partnership with the Richmond Fed and Duke University, and the Survey of Business Uncertainty with economists from Stanford University and the University of Chicago.

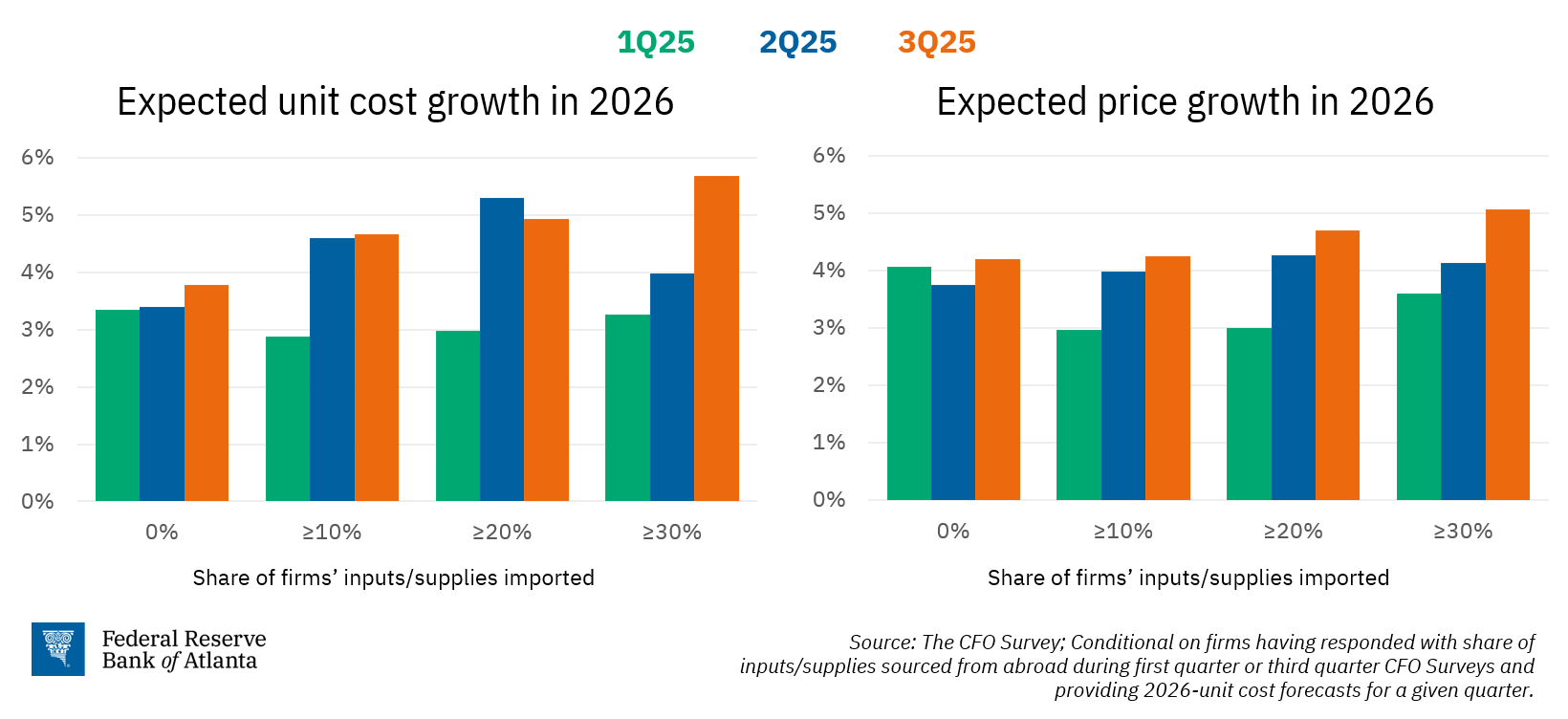

Evidence from all three surveys points decisively in one direction—continued upward pressure on costs and prices. Start with this picture (chart 3). This first column is what firms in the CFO survey told us early this year: basically, their price and cost expectations for 2026 continued upward. Then in the second quarter—after the original round of tariff announcements in April—expectations climbed further, particularly for importing firms. When we asked about this again in the third quarter, firms' price expectations for 2026 ticked up still higher.

Chart 3

The upshot is that firms in our survey expect to raise prices well into 2026, and by substantially more than 2 percent. What is especially compelling and concerning is that inflationary expectations are not confined to importers directly affected by higher import duties. On the contrary, our surveys reveal considerable spillover to other firms and other motivations for raising prices, such as increases to match those of competitors. In other words, there is space to raise prices, and so, as one would anticipate, profit-maximizing firms indicate that they plan to do just that.

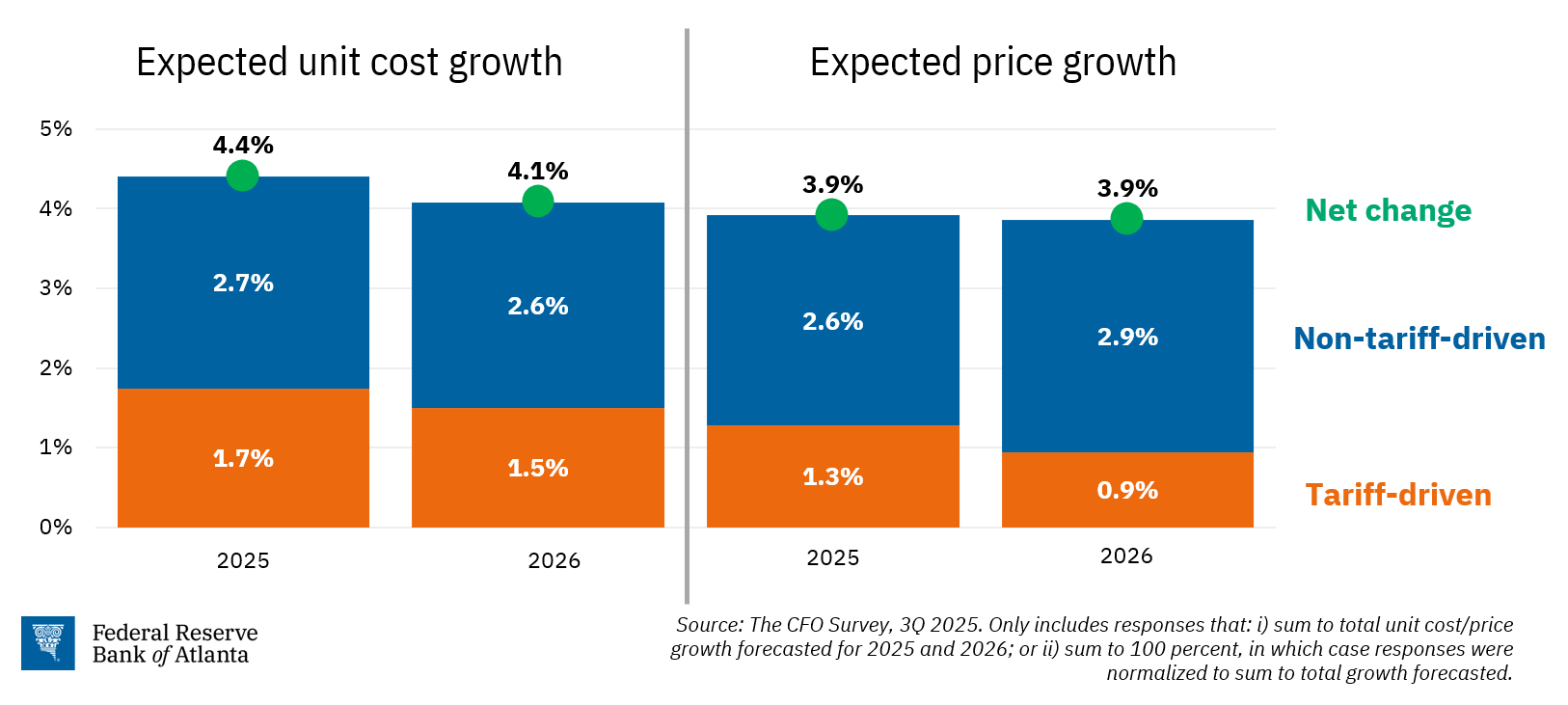

This next picture (chart 4) shows that respondents in the CFO Survey—all firms, not just those directly exposed to tariffs—expect to raise prices just as much in 2026 as in 2025, and much of that impulse is not driven directly by tariffs. Moreover, we find that expectations for operating costs continue to climb as well.

Chart 4

On average, firms assign just under 40 percent of their total unit cost growth in 2025 and 2026 to tariffs. Firms also assign one-third of their price growth this year to tariffs and around one-quarter of next year's price growth to tariffs. These findings point again to the reality that price pressures extend beyond tariff effects. As such, it would appear unlikely that cost and pricing pressures will evaporate when tariff policies are finalized, whenever that may be.

Now, I might be less firm in my stance if we detected faint stirrings of inflationary sentiment from a single question tucked into one survey, or from a small minority of respondents. But that is not the case. This evidence of continually rising costs and prices comes from all three of our primary surveys of business decision-makers across industry sectors and geographies.

I take these findings very seriously for two reasons in particular. One, the survey data are especially useful when traditional data we rely upon are absent, slow in coming, or incomplete, like during the government shutdown. Second, our survey results have proven to be reliable gauges and predictors of actual economic activity. Our BIE survey's unit-cost realizations have tracked the patterns of aggregate inflation quite closely in recent years, as you see in this picture (chart 5). The blue line shows BIE survey respondents' reported unit costs, and the green shows inflation per the GDP deflator, the broadest overall measure of inflation.

Chart 5

What's more, expectations of prices, costs, and sales gleaned from the three surveys have a good track record as predictors of events. We've found that businesses' unit cost expectations are generally more accurate in forecasting inflation than households' inflation expectations and are at least as accurate as professional forecasts. Point being, the survey results are as good as the best forecasts.

I should add, as a caveat, that our survey results date mostly from the post-Great Financial Crisis period, so they have not been tested at a major economic turning point. (I don't count the pandemic because it was so extraordinary and did not emanate from economic forces.) In fairness, the traditional "hard data" suffer from the same problem, as signals like the unemployment rate are lagging indicators.

So, I take heed when these firms' leaders say something is likely to happen.

Taken together, this evidence from surveys, buttressed by additional research and anecdotal input from price setters, reinforces my view that we cannot breezily assume inflationary pressures will quickly dissipate after a one-time bump in prices from new import duties. Across all our information sources, I see little to no evidence that we should be sanguine about the forward trajectory of inflation.

That gets me to the real rub: If inflationary forces lurk for many months to come, I am concerned that the public and price setters will eventually doubt that the FOMC will achieve the inflation target. Does that happen after five years of above-target inflation? Six years?

I don't know. But serious trouble awaits if inflation expectations for the medium- and longer-term drift upward and influence behavior in ways that produce higher long-run realized inflation. Should those things happen, history suggests that some pain, in the form of higher unemployment, could be required in order to move inflation expectations back into the long-run target range.

So far, though some measures of inflation expectations have bumped up, by and large, we have not seen a worrisome unanchoring of longer-term inflation expectations from businesses or consumers. I will be watching measures of expectations very closely, as the Committee's revised monetary policy framework explicitly calls out the primacy of inflation expectations.

Labor market is shifting, but is it weakening?

Turning to the sustainable maximum employment side of the Fed mandate, the labor market is unquestionably shifting in uncomfortable ways. I say "shifting" rather than "weakening" because I don't read the available indicators from recent months as a clear signal that the labor market is weak.

This is a nuanced distinction—shifting versus weakening—and I'm going to frame my explanation of it with a question that I think is receiving too little attention. That is, what is the underlying nature of the labor market shift? How much stems from cyclical forces rooted in labor demand and thus shaped by aggregate macroeconomic demand? Those would be factors monetary policy may address.

On the other hand, how much of the shift in labor markets results from more structural forces largely beyond the influence of monetary policy? These structural dynamics would include reduced immigration, an aging population and meager population growth, and the deployment of labor-replacing technologies. In addition, the stated motivations for tariffs—including a fundamental restructuring of supply chains and the nation's industrial mix—would almost certainly disrupt the labor market over the long term, should those developments happen.

Even though I'm raising this cyclical versus structural question, I admit I lack solid answers. To be honest, I don't think anyone has clear answers at this point. But we need answers for many reasons, an immediate one being the implications for monetary policy. If we are in fact experiencing the early stages of a cyclical downturn in the labor market, then monetary policymakers may need to respond. By contrast, if labor market shifts reflect secular forces, then the ideal first-level policy response would likely not come from monetary policy.

Few compelling signs of a cyclical downturn

Let's look at cyclical factors first.

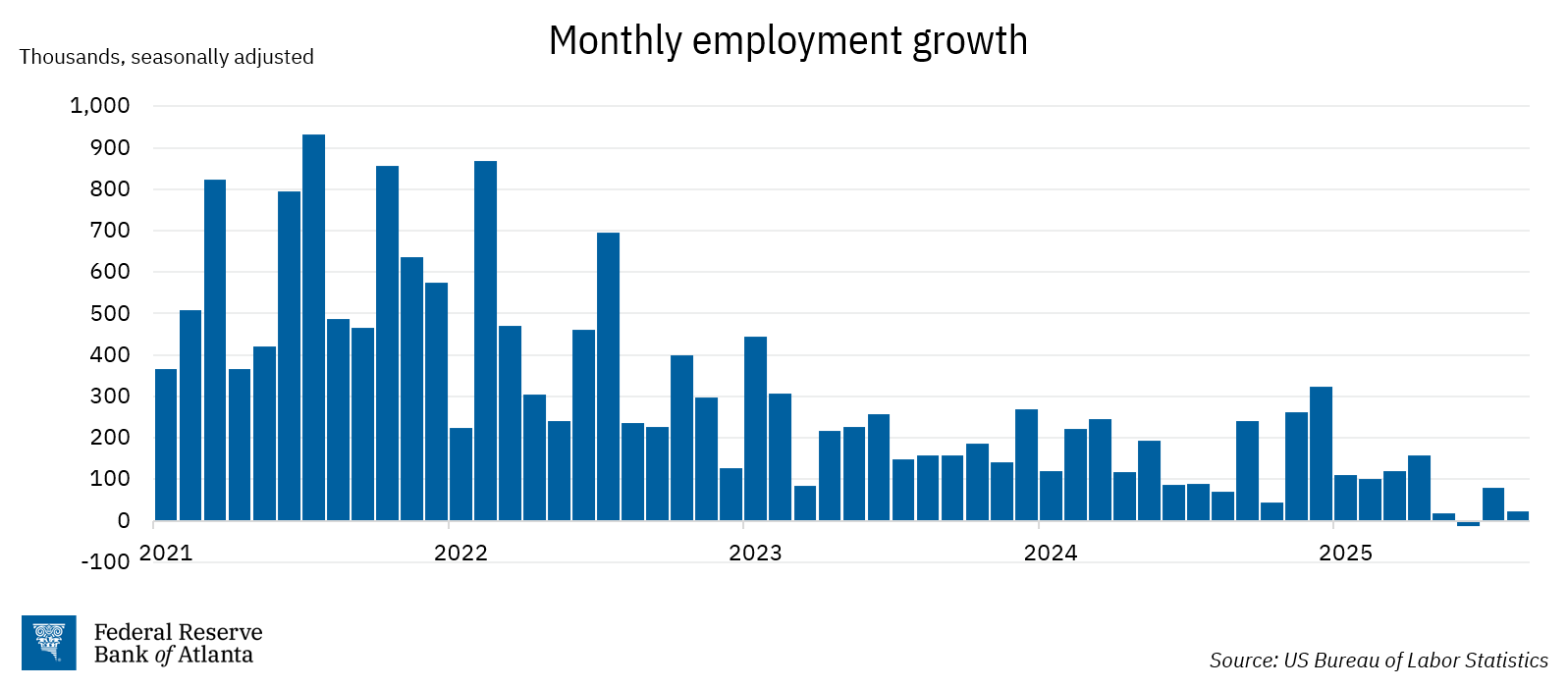

The latest aggregate data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (chart 6), which admittedly are growing stale, tell us monthly payroll employment growth has slowed markedly—to an average of 29,000 in the three months through August.

Chart 6

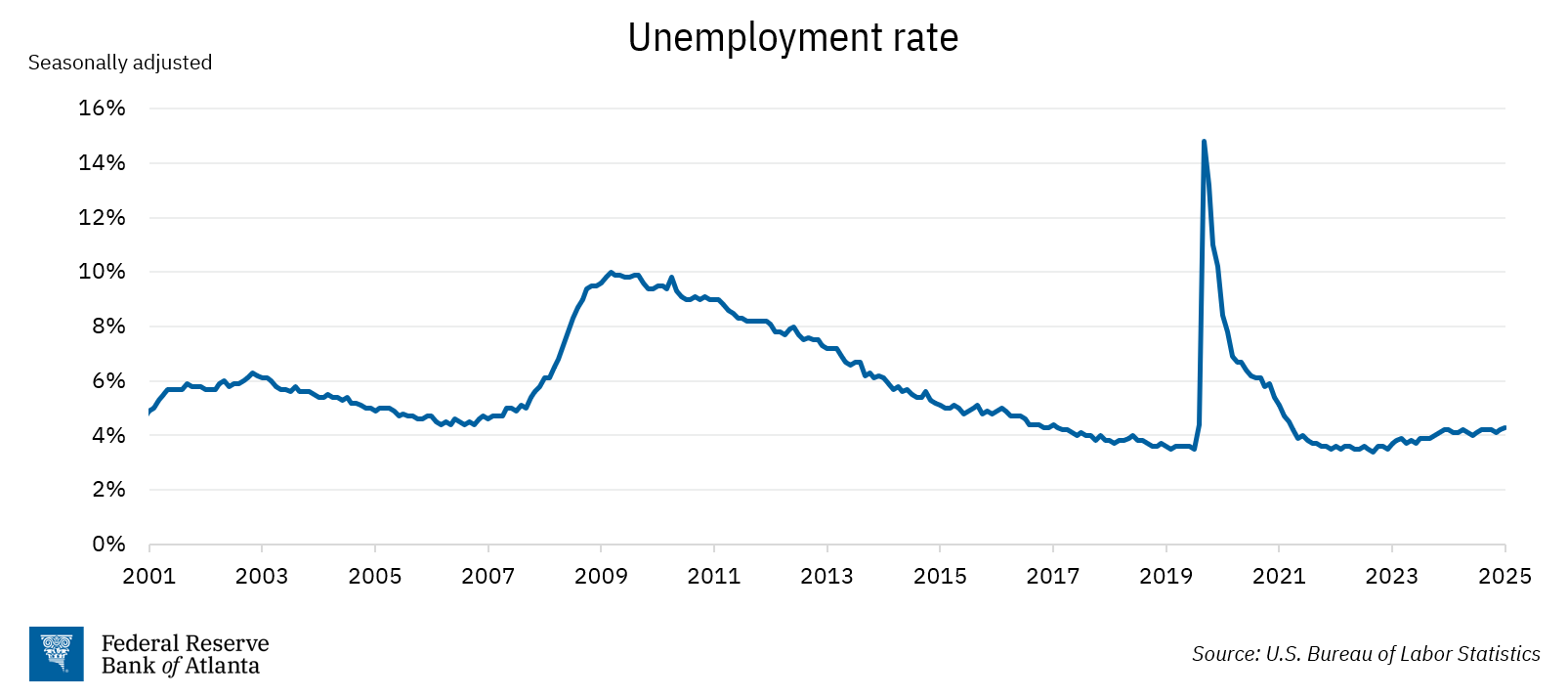

Even as hiring has tapered off, the broadest measure of labor market balance—the headline unemployment rate—has barely moved (chart 7). It inched up to 4.3 percent in August, a modest increase from an average of 4.1 percent in the first quarter of this year and 4.2 percent in the last half of 2024. Essentially, then, the unemployment rate is unchanged over the past 12 months of available data.

Chart 7

The bottom line is, the headline unemployment rate is characteristic of a balanced labor market. But maybe there is weakness that is not captured in the headline jobless numbers? Not yet anyway, per the data we have. The broader U-6 unemployment rate that accounts for the unemployed plus those working part time for economic reasons and marginally attached to the labor force has also climbed just slightly—to 8.1 percent in August from 7.8 percent the year before.

The official employment data are aging a bit. So, what do alternative sources tell us? The more real-time indicators my staff and I consult reinforce the story described by the official data—a labor market in a curious state of balance but a state of balance nonetheless.

Some of the best information we gather comes from talking to business decision-makers across our six-state district. A team we call the Regional Economic Information Network—or REIN—conducted more than 700 interviews this year. Those reveal growing apprehension among firms toward payrolls, certainly. Yet, in the main, the sentiment describes a "hiring chill," as one contact called it, rather than a freeze.

Other non-governmental sources paint a similar picture.

One of my favorite gauges of broad labor market conditions is the Kansas City Fed's Labor Market Conditions Indicators. This index aggregates two dozen labor market variables to produce measures of labor market momentum and level of activity. Economists there constructed an alternative measure with non-government inputs, and those readings suggest that the labor market is continuing to moderate at the same steady rate we have seen over the past two years. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago's real-time estimate of the unemployment rate was at 4.36 percent in October, again not indicating a dramatic downturn in the labor market.

Finally, our October Survey of Business Uncertainty finds that respondents' year-ahead expectations for their own employment growth were just a smidge lower than in January and actually higher than they were in the spring.

In totality, the official data we have, along with the alternative measures I follow, suggest to me that the labor market is not obviously in a state that demands strong monetary policy medicine. And in any case, before we prescribe remedies for the hiring chill, it is important to diagnose the underlying condition.

As I mentioned earlier, the vast majority of our business contacts tell us their hesitation to add to payrolls fundamentally stems from painful increases across a range of business expenses: materials, insurance, healthcare, utilities, various services, and labor. In most cases, firms lack or have exhausted easy ways to offset this array of cost shocks. They can't lean solely on price increases, as customers have grown increasingly price sensitive. So, firms have turned inward in the search for expense reduction, and, for most businesses, labor is the largest expense.

Given those circumstances, it is not surprising that most firms are not adding staff. Some are slimming down through attrition, while others are planning or conducting layoffs. Contacts describe a complicated blend of rising costs and moderating demand that is pressuring margins, forcing cost cuts that recently include headcount reductions. The general characterization is that firms are selectively trimming payrolls as opposed to desperately laying off huge numbers of workers in the face of plunging demand. One of our REIN staff noted that not a single contact uttered the word recession leading up to the October FOMC meeting.

Structural forces in the labor market

Put simply, I'm not detecting unambiguous signals of a serious cyclical labor market downturn. What about the structural forces shaping the labor market?

These affect both the demand for labor and the supply. On the supply side, Atlanta Fed economist Julie Hotchkiss untangled numerous dynamics that have combined to suppress labor force participation for more than 12 months now.

Julie found that a reduction in the foreign-born share of the population and an accompanying fall in their labor force participation rates contribute heavily to the recent decline in the aggregate participation rate. Beginning in late 2024 and intensifying this past summer, participation has declined dramatically among foreign-born workers who have lived in the United States for at least five years.

My staff tells me we will likely not see the full labor force effects of immigration policy changes until 2026 and beyond, what with the southern border effectively closed, and deportations likely to increase with planned expansion of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency.

Let me be clear: Immigration policy decisions are properly made by elected officials. I'm not here to advocate in that space one way or the other. I can say the data clearly tell us that foreign-born workers have accounted for the bulk of US labor force growth in recent years because fewer native-born Americans have joined the workforce. Consequently, shutting off migration will inevitably have important implications for labor markets.

And immigration is not the only factor limiting labor supply. Indeed, if demographics are in fact destiny, then the US labor force is destined to barely grow for years to come. Despite strong participation among prime-age workers, those aged 25 to 54, the "gray wave" is more powerful. Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show the ratio of US births to deaths has declined for nearly 20 years. And there's no end in sight to that trend. The latest estimates from the Congressional Budget Office show that, without immigration flows, the US population will actually start to shrink in less than a decade—by 2034.

What's more, the future population will almost surely be even more weighted toward senior adults who are least likely to seek work—the share of the population age 65 and over, 17 percent now, figures to be 22 percent by 2040.

I could do a whole speech on demographics, but that's for another day.

For now, I'll briefly discuss an additional dynamic that could suppress labor demand in the long term. That is the way business leaders are rethinking the labor implications of technology, particularly artificial intelligence (AI).

Growing numbers of decision-makers tell our team and other surveyors that they are coming to view technology more as a replacement rather than a supplement for labor. So far, younger workers in occupations exposed to AI appear to be affected the most, as the unemployment rate for recent college graduates has risen sharply.

No doubt the story on AI is in its early chapters. But I think the implications could differ from those of earlier innovations, like electricity and the steam engine, because AI is so accessible that it can diffuse through society faster and more broadly. The takeaway here is that I believe the way firms are refining their approaches to technology adoption could augur a longer-term, secular development with serious implications for the number of workers firms will need.

As for fundamental shifts in supply chains and the nation's industrial mix, it is premature to draw sweeping conclusions. We have heard from some large firms that have "near-shored" or "friend-shored" production and sources of inputs. Those are long-term, costly moves that are generally beyond the reach of smaller firms.

Those are some of the structural forces buffeting the labor market that I believe the research community needs to wrestle with.

Grounding my approach in the strategic policy framework

Big picture, as we sit here today, I do not view a severe labor market downturn as the most likely near-term outcome. If we were experiencing broad-based cyclical labor market weakness, I would expect to also see signs of broader economic softening. That's not showing up on my radar.

The most recent estimate from our GDPNow "nowcast" model is for 4 percent gross domestic product growth for the July–September quarter. An alternative version of GDPNow that encompasses several alternative, non-government data sources show much the same result—3.8 percent for the third quarter. Regarding aggregate demand across the economy, feedback from contacts points to moderation; not an abrupt plunge.

Let me assure you that my position on the state of the macroeconomy and the appropriate monetary policy stance is not immovable. I talk to people. I listen. I see the data.

I appreciate the concerns of colleagues and other economy watchers. I acknowledge the significant stresses lower- and moderate-income households currently feel; the "K-shaped economy" descriptor seems apt. And I would be remiss not to acknowledge the real pain that is already afflicting segments of the population. The unemployment rate for Black Americans is over 7 percent after dipping below 5 percent in 2023. The jobless rate for recent college graduates has also climbed appreciably, and the average spell of unemployment is nearly a month longer than it was a year ago.

Labor market shifts mean the two mandated objectives are much closer to balanced than they were a year ago, or even several months ago. For a while now, I have been conducting straw polls at every meeting I have, whether it be with contacts, staff, or boards of directors. A year ago, those votes were 14–1 toward inflation as the bigger risk. Now, it's 8–7 or even weighted toward employment as the larger problem. The heads of our regional branch REIN teams voted 3–3 at our last meeting. Trust me, these polls are unscripted, and the consistency of the results over windows of time has been uncanny.

Yes, this feedback represents a significant shift in sentiment, which I do believe is representative of the broader mood. I weigh that seriously.

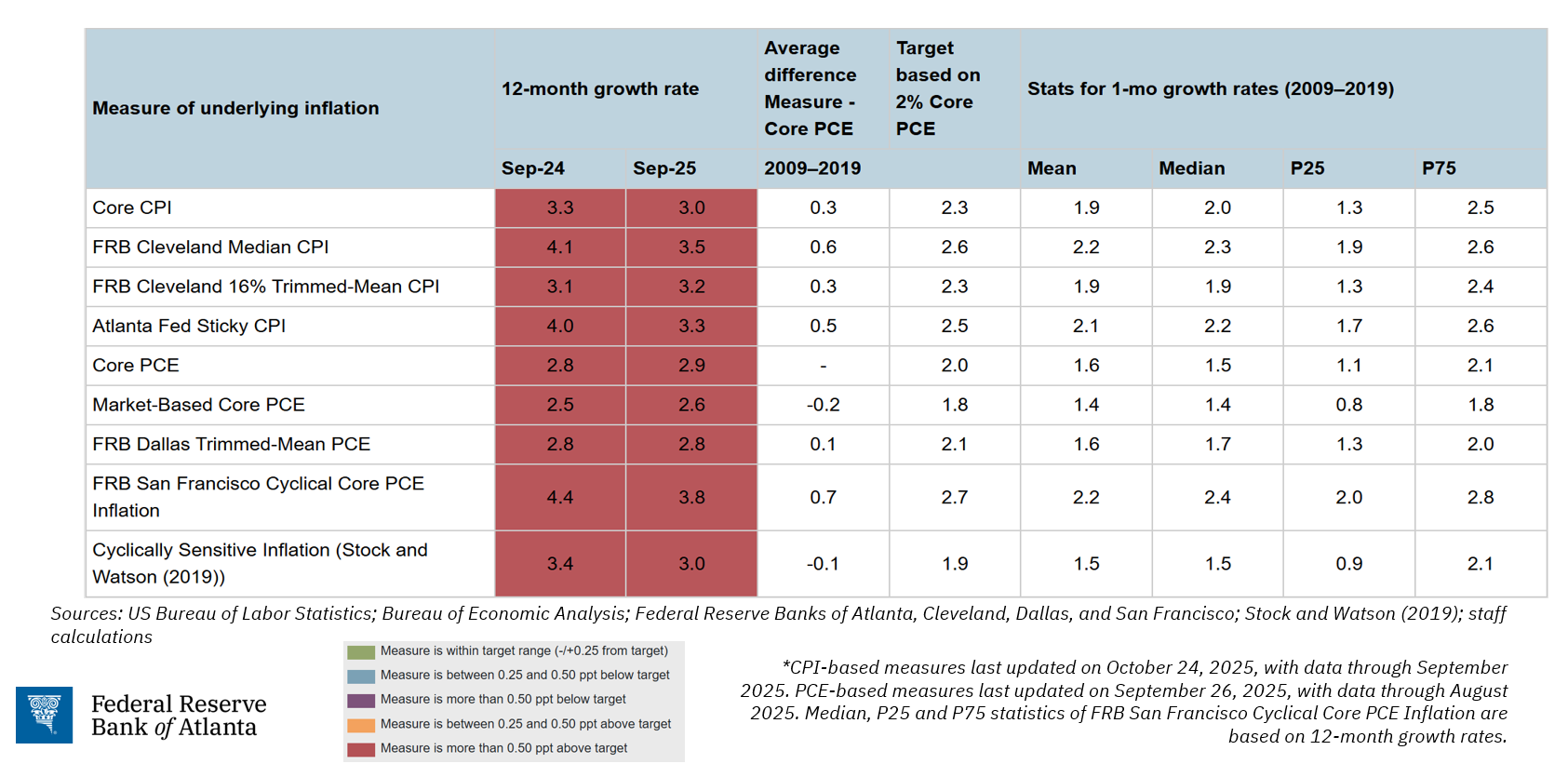

So, it's definitely a close call. But in the final analysis, I view the signals from the labor market as ambiguous and difficult to interpret. They are not clear enough to warrant an aggressive monetary policy response when weighed against the more straightforward risk of ongoing inflationary pressures. This slide (chart 8) shows our Underlying Inflation Dashboard. I think the name is self-explanatory. It shows numerous measures of fundamental price pressures. Red means too high. As you clearly see, the table is bathed in red.

Chart 8

In these circumstances, moving policy near or into accommodative territory risks pumping fresh blood into the inflation beast and threatening to untether the inflation expectations of businesses and consumers. I simply do not think that is the proper trade-off we should contemplate right now.

I view the Committee's monetary policy today as marginally restrictive and favor keeping the funds rate steady until we see clear evidence that inflation is again moving meaningfully toward its 2 percent target. By my lights, that is an appropriate position in this volatile environment. You doubtless realize my view is not unanimous at the FOMC, or even here in this building. That's fine. My colleagues and I here and at the FOMC engage in robust discussion in pursuit of optimal policy outcomes.

I am grounding my approach to the policy trade-offs in the Committee's revised policy framework. When the mandated objectives are in tension, the strategy directs participants to determine which goal is most distant and will take longer to reach. The goal that is farther over the horizon takes precedence: If price stability is farther away, then policy should be somewhat restrictive or perhaps more restrictive than at present. If sustainable maximum employment is more distant, then policy should be more accommodative.

To reiterate, I view price stability as the more urgent priority. Of course, if conditions change materially, I am willing to alter my stance. More generally, moving forward I will be guided by the data and qualitative information in hand, my outlook, and my assessment of the balance of risks to our mandates as the Committee seeks to achieve price stability and sustainable maximum employment for the American people.