If the 1950s were prosperous and complacent, at least compared to the 1930s and 1940s, the 1960s brought tensions, occasional turmoil, and a faster rate of change. To the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta they brought breakthroughs in automation, Cold War contingency planning, civil rights, and a key change in leadership.

The New Orleans branch of the Atlanta Fed, ca. 1968. |

The paper-moving factory starts to hum

Even in the Sixth District, where credit was emphasized, the Bank's role as a processor overshadowed its role as a lender. The days of the largely manual clearinghouse were peaking in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The Atlanta Bank's staff, largely an army of efficient clerical workers, swelled to 1,444 by 1960. Of a 1958 budget of $9.8 million, 55 percent ($5.4 million) went for employee salaries. The Bank worked hard to take a progressive, enlightened approach to managing its staff. Frank Neely's ghost still roamed the halls: efficient organization, good working conditions, incentives for high performance, good compensation, benefit packages, and formal review and training procedures all were embedded in the policies of the Bank. Efforts to attract young, well-educated administrators continued. Often the youth movement put Bryan in conflict with the old guard, well represented by New Orleans manager Morgan Shaw, who still wanted to see seniority rewarded. The officers generally favored in the 1950s were better educated than their predecessors, particularly in economics, but they included few of the technological whiz kids who would become so important in the 1970s.

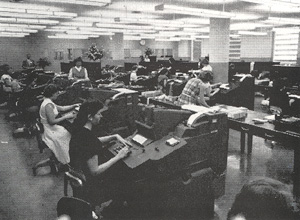

In spite of the vast amounts of processing that it did, the Bank entered the 1960s still largely unautomated. Efficiency was prized and measured, but it was usually manual efficiency. A visit to the check-processing department of a high-volume office like Atlanta or Jacksonville would mean walking into a room in which 70 to 85 women sat busily clicking away at gray, 36-pocket IBM 803 proof machines, punching in payment amounts and bank identification numbers with one hand and, with the other hand, picking up checks one at a time from a stack and pushing them into a slot. The machine sorted the checks into pockets for eventual return to the bank on which they were drawn, while a record of the activity was printed on paper tapes. A skillful operator could handle 1,200–1,500 checks per hour.

Systemwide comparisons in 1961 showed Atlanta doing fairly well in most areas. The Bank was particularly proud of the ability of its staff to spot counterfeit currency. Yet Atlanta ranked last among the Reserve Banks in currency and coin handling efficiency. The Bank went to work on the problem and was able to raise its output from 2,208 to 3,193 pieces per man hour, enough to bring Atlanta to a third- or fourth-place performance level, First Vice President Harold Patterson estimated in 1962.

What would become an operations revolution started quietly in 1957 with the establishment of a "Methods and Systems Committee," formed "for the purpose of promoting efficiency," according to the minutes. It took over from auditing the job of reviewing operating procedures throughout the Bank. From personnel, it inherited the task of preparing job descriptions and training literature.

Technology already was beginning to make small inroads into Bank operations as the 1950s waned. Facsimile transmission equipment was acquired in 1958 to handle orders for wire transfers and money shipments. A data processing department was formed in 1960, combining the central tabulating unit with the machine tabulating unit of the Fiscal Agency Department. And by 1960 the Methods and Systems Committee had undertaken a major study to determine the feasibility of installing the Bank's first computer. In 1961 Bryan told the board, "The bank is expecting to acquire an IBM 1401 computer by the end of this year and is engaged in training the operating personnel and devising programs for numerous records to be kept by the machine." The computer entered the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta in January 1962. It was an IBM 1401, acquired tentatively on a rent-to-buy basis. By July, it was there to stay, bought for $230,000. Various records were transferred to the computer during 1962.

Automated check-clearing equipment greatly improved the efficiency of the Bank's operations. |

Automation tackles the paper piles

The advent of the computer in the Atlanta Fed was overshadowed by the coming of automated check processing equipment. As the flood of checks threatened to engulf the payments system, bankers and Fed officials, in the late 1950s, had developed a system for encoding checks with magnetic ink character recognition (MICR) numbers. Such checks, in theory, could be read by machines, and now the prototype machines were proving viable at five Federal Reserve Banks where they were being tested. A unit could be installed in the Atlanta Bank by the third quarter of 1962, officials said. Economist Lloyd Raisty had observed the equipment in operation in another Reserve Bank and reported that it would substitute machines for people and change the employment patterns of the Bank. The conversion to automation was about to begin.

It was a landmark event, in November 1963, when the Bank installed an IBM 1420 high-speed bank transit system. It could process 50,000 checks per hour, more than 40 times the output of an average proof machine operator, making it possible for the check collection department to reduce its staff by 15, a member of the methods and systems department told the board. By June 1964 the speedy machines were working well in both the Atlanta and Jacksonville offices and slated for installation in the other branches. A drop in personnel from 1,412 in 1959 to 1,351 in October 1964 was attributed both to automation and to other efficiencies created by better management.

An item in the May 1965 6-F Messenger, the Bank's employee magazine, captured the attitude of some of the operators toward the rapidly disappearing 803 proof machines:

| Farewell IBM 803, with your buttons in a row, Your tapes standing like sentinels, your control lights all aglow. Your knobs, your levers, your coat of grey, will soon pass from our sight. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . We'll empty no more pockets that are full, no tapes to pull or replace. We'll curse and swear no more at you, or rush to set a pace. Your replacement's coming soon, old friend, a computer, fine and fit. But it won't be long, I feel sure, before a replacement replaces IT. |

Currency handling was harder to automate. It would be another 15 years before machines would be perfected that could count and sort currency, allowing the same kind of transformation in cash services.

Holocaust contingency plans

The 1962 Cuban missile crisis revived fears of a nuclear war and caused the Atlanta Bank to review its emergency preparedness program. If Atlanta were hit, headquarters responsibility would transfer to Nashville, with Jacksonville the second backup. Senior officers throughout the District had sealed orders to open and follow in case of an attack. System records were maintained in all branches, as well as the secure records center built in 1954 in Auburn, Alabama. The records center was staffed around the clock, and its records were kept up to date.

If contact with the Federal Reserve Board were lost, the Atlanta Bank would operate autonomously, honoring checks on any bank, regardless of whether anyone knew if that bank still existed. The Atlanta Fed would provide a market for government securities, continue fiscal agent activity, and supply liquidity through credit in whatever way seemed practical. Some Reserve Banks placed large amounts of cash in scattered commercial banks for emergency use, but in the Sixth District, with its five offices, such an arrangement was considered unnecessary. The emergency plan was grimly specific and showed how ominous international tensions were in 1962. Fallout shelters had been built in the new buildings in Jacksonville, Nashville, and Birmingham and were planned for the Atlanta and New Orleans offices.

Integration at the Fed

What exploded in the Sixth District, however, was not the atom or hydrogen bomb but the civil rights movement. Nothing since Reconstruction so rocked the District. Through most of the 1960s angry confrontation and violent protest sometimes bordering on war convulsed the deep-South states of Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. The shock waves were felt inside the Bank, which was both a southern and a federal institution, but faintly. There was tension and anxiety but no incidents of racial conflict. The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta accepted integration sooner than much of its region.

The Bank was still substantially segregated in January 1962, when President Bryan got word from the Board of Governors that the situation must change. The officers, guards, and clerical work force were all white. The custodial staff (at that time employees of the Bank) were all black. The cafeteria had been officially integrated six years earlier, but blacks used separate rest rooms. An NAACP official had objected, and the Board in Washington was, in Bryan's words, "deeply disturbed."

Conceding that the separate facilities were by no means equal, Bryan gallantly volunteered to isolate his board from touchy integration decisions and tackle them as administrative problems. The directors, however, voted unanimously to give their full support to Bryan's efforts. While he intimated to the board that he would "try to find some discreet language" to desegregate the Bank's rest rooms, he issued instead a detailed, explicit memo to the entire Bank staff on the rationale and etiquette of integration, pleading for their cooperation. Then he held his breath. Some white employees did quit, but there were no confrontations or protests.

Bryan was adamant on one point, however: there would be no quotas and no bending of the standards for black applicants. "[W]e will put the Negro employees through precisely the same tests of ability, responsibility, personal acceptability, and all other matters" expected of white applicants, he insisted. He defended the Bank's tests as scientific and racially neutral. Applications by black people for previously "white" jobs came slowly. One woman from the night cleaning force in February 1962 had requested a day job, and there was a clerical opening in the fiscal agency department. "[S]he was given our battery of clerical aptitude tests, which she passed with entirely satisfactory scores. . . . [S]he has now completed her third week in the department and she has been received on the whole with great courtesy by our white employees. Such small discourtesies as have been shown her have been minor items, such as not speaking. This has caused the girls in her particular section to rally to her support and defense, and I expect that she will be one of the best trained clerks in the Bank," Bryan reported in March 1962. A black man joined the guard force in 1964 after learning to shoot well enough to pass the marksmanship test, the only test he did not pass on his first attempt. By November 1968 the Bank, satisfied with its success in placing blacks in clerical positions, was visiting black universities to try to recruit black managers and future officers.

Bryan's gloom

The strains of office were weighing on Bryan. He was easily upset, and there was much to upset him in the 1960s. The integration order upset him. The building problems upset him. But most of all the economy upset him. As his years at the Bank advanced, his view of the American economy grew steadily gloomier. To a bright, idealistic economist, the New Deal programs, the World War II mobilization, and the flowering of the postwar industrial economy provided a wonderful opportunity for an economic utopia. Now that opportunity was being betrayed, and the economy was being looted, it seemed to Bryan—not by the Federal Reserve System in which he had placed so much faith, but by the fiscal policies of the federal government with which it had to coexist. Gold supplies were draining quickly in 1962, he noted, and the link between gold and paper money was starting to dissolve, a situation he regarded as pointing toward ruin.

Bryan, the compulsive economic analyst, began to sound increasingly like Jeremiah. In February 1965, as the Lyndon Johnson "Great Society" programs rolled into view, Bryan told the Atlanta board, "In my judgment, we have behaved with such financial imprudence that I think we have to free up some of our gold to meet a possible run on gold. . . . I am deeply discouraged about it because I think this is but one of a series of steps that eventually leads this country to a regime of fiat money in which, so far as I know, no country has ever succeeded in operating for long. . . . In my guess, sooner or later, and we may be utterly startled by the speed with which it will occur, we will go to a vast inflation in this country." The current period, he suggested, might be "a prelude to war."

When things weren't going well, which was increasingly the case, Bryan would withdraw to his office and pace. He was, by 1965, clearly a troubled man. He also was ill. An undiagnosed brain disorder, later determined to have been a series of small strokes, was progressively destroying his ability to walk. It interfered with his attendance at Open Market Committee meetings and may have aggravated his dark moods. It was time for him to step down. He did not use health as a reason when he told Chairman Tarver he intended to resign. He said he wanted to give Harold T. Patterson, his first vice president, a chance to manage the Bank. Giving Patterson a chance was by no means a long-range solution to the problem of succession, however. Patterson was himself 62 years old and suffered from Parkinson's disease, although it had not yet reached its debilitating stages. Other veteran officers coveted the presidency, but Bryan and Tarver agreed that the proper man for the job was not among them.

Bringing in "Bones"

For the first time since the Bank opened, the Atlanta Fed would have to reach outside its official family (if Bryan's own sojourn at Trust Company did not remove him from the official family) for a top leader. But the Bank would not have to reach far outside because one of its own directors looked like a good catch. Monroe Kimbrel had joined the board in 1960 as a Class A director. Kimbrel, years earlier, as a student from Colquitt, deep in rural southwest Georgia, had sat in rapt attention in a large lecture hall at the University of Georgia, listening to Professor Malcolm Bryan explain economics. Kimbrel then became a banker and businessman, starting a hardwood lumber business in Thomson, Georgia, and rising to become chairman of the First National Bank there. He was elected president of the Georgia Bankers Association in 1956, then the youngest president of the American Bankers Association (ABA) in 1962. All this exposure had made "Bones" Kimbrel, as he was widely known, arguably the most popular banker in America. He was not an economist in the Bryan mold, but he had a gift for making others feel important. He was a "people person," a motivator and an apparently able administrator, although he had never run a large organization for any length of time. The Bank could use a sunnier chief executive who had a knack for drawing out the best in people around him, Tarver and Bryan agreed.

Kimbrel was asked to come into the chairman's office after a board meeting. Tarver and Bryan were waiting there to talk to him. Tarver did most of the talking, Kimbrel recalls. Tarver asked Kimbrel to join the staff of the Bank with the understanding that he soon would become president. After his extensive travels with ABA, Kimbrel wanted to return to Thomson and his banking and lumber interests, but he was facing other pressures that Tarver and Bryan didn't know about. Georgia Senator Richard Russell wanted Kimbrel to come to Washington as Comptroller of the Currency. He had worked out the details with the Johnson White House for Kimbrel's appointment. Neither Kimbrel nor his wife wanted to move to Washington. However, he could see that, after the exposure of being president of the ABA, a quiet return to Thomson would be difficult. So a few days later he chose Atlanta over Washington and accepted Tarver's proposal. He resigned as a director and was named senior vice president, a title used by the Bank for the first time to identify Kimbrel as its third-ranking officer. On June 1, 1965, he reported for work at the Bank. He worked closely with Bryan through that summer, learning how the Bank and the System operated. It was understood in all quarters that he was the president-in-waiting. He had a letter to that effect from William McChesney Martin.

Harold T. Patterson, Atlanta Fed president from 1965 to 1968. |

Bryan, failing more quickly than expected, announced in August his resignation, effective October 1, 1965. He refused a dinner or a portrait but endured a brief observation of his retirement at the September board meeting, where Chairman Tarver expressed "tremendous sorrow" at the ending of "the Bryan era." Bryan, even in consciously avoiding discussion of the economy, could not help alluding to it. "[M]y views of the long run economic situation in the world are so dismal that I have decided to spare the Board of Directors my animadversions," he noted at the beginning of his brief remarks, probably with a smile. But it is unlikely that he was smiling a few moments later when he confessed, "I look with a certain terror at what seems to me to be a gradual weakening of the Federal Reserve System in the maelstrom of politics." Eighteen months later, on April 18, 1967, he died of a heart attack.

Patterson has his day

With Bryan's retirement, Kimbrel, then in his fifth month at the Bank, advanced to first vice president and continued to learn the System.

The man who became president never aspired to be more than an interim leader. After 13 years of dealing daily with the volatile Bryan (eight as vice president and general counsel and five as first vice president), Patterson was ready to take his hour in the sun, and he held the office from October 1965 until his own retirement on January 31, 1968. Patterson was a wealthy, socially prominent attorney, whose circle of friends included the Frank Neelys. He enjoyed joking with associates. He suffered through the public speaking obligations of his office, however, and was uncomfortable making major decisions, Kimbrel recalls. As a result, Patterson was happy to delegate a great deal of responsibility to his first vice president.

One of Patterson's first decisions as president was to revive the bank visitation campaign. Another of his favored projects was the publication of the Bank's history. During Bryan's last year as president, the Bank celebrated its 50th birthday. Atlanta historian Franklin Garrett had been commissioned to write and compile a history of the Bank. Patterson nudged forward plans to publish the 1,367-page typescript, but printing had not yet begun when he retired, and one of Kimbrel's first decisions as president was to not publish what he considered an unwieldy account.

| Previous | Next |