Putting out fires became the first order of business of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta during 1930, 1931, and 1932. The first one broke out on September 26, 1930, in Havana. In a remarkable instance of deja vu, a run on Cuban banks exhausted available currency and placed the banks in a serious bind over the weekend of September 27-28. A special train carried $25 million in currency from Atlanta to Key West, where it was met by the gunboat "Cuba." The boat got the money and Federal Reserve officials to Havana in time to break the run, and the situation returned to normal. This time, however, there was no rival Boston agency, and there were no repercussions.

A second, more troublesome fire broke out in November 1930 in Nashville, when the bond house of Caldwell and Company failed, precipitating a run on local banks. Black went to the scene, with assistant cashiers Bowman and H.F. Coniff from Atlanta, and helped the Nashville branch supply currency and credit to member banks. As a result, no bank was closed, "due in part to the efforts of the Reserve Bank," Black explained to his board in a report on November 14. He had returned to Atlanta on Saturday, November 8, but the next day received word that the Holston-Union National Bank of Knoxville was in trouble. "Mr. Coniff was immediately sent there and I immediately went to Nashville. I spent Monday and Tuesday in Nashville endeavoring to aid in the Knoxville situation in any way that I could and endeavoring to hold the Nashville situation in check. Little aid could be rendered the Holston-Union National Bank because of its condition and because of its large present borrowings from us. The Holston-Union closed today, November l2th, and there has been a run on the City National Bank of Knoxville and the East Tennessee National Bank of Knoxville. This run was caused by certificate holders and savings depositors. About $500,000 was drawn out of each bank today. These two banks with other banks have invoked the thirty day clause on certificate holders and savings depositors. . . . We are shipping sums to these two banks in Knoxville which will be adequate for any demand made upon them and I am hopeful that the situation there has been relieved."

Black, with his excellent skills at managing people, was evidently an effective emissary. His work with a crisis that developed in New Orleans early in 1933 brought this testimony from one of the affected bankers, expressed in a letter to Chairman Newton: "Mr. Black left this afternoon after having spent five strenuous days with us. . . . I don't know how we could have ever got the results we did without his splendid cooperation and his patience and tact, which held all the various interests together at all times. . . . [T]he whole city of New Orleans owes him a real debt of gratitude for his untiring and effective work."

Liquidating failed banks

Black had a grim report to offer to the Atlanta board at its January 1931 meeting: "The closed banks now being handled by us are 54 in number. Their liability at date of closing was $14,209,298.58. Of this sum we have collected $7,390,420.71; having charged off $1,545,825.09; have recovered $60,437.40, and as against any further liability we have reserves set up of $1,303,490.33."

A page of the Atlanta Fed's ledger book from 1935 shows "Loss, on account of death, of cow . . . $1.00." |

Aside from the dollars and cents, the Bank was waging a psychological battle as well. "Uneasiness exists all over our District, following the failures throughout the country," Black went on in his January report. "[I]t is appalling to consider that during 1930 banks closed in America with an aggregate of deposits of $700,000,000. This has brought consternation in the localities where banks have closed; and looked at from a cold business basis it has very largely curtailed buying power throughout the nation. The energies of every officer of our bank are directed toward relieving the situation that can be relieved in our own District and these efforts will be continued."

By October 1931 Black shared with the board the Bank's growing experience with liquidations: "We now have 58 suspended member banks in the course of liquidation . . . all located in small cities or country towns" except for one each in Knoxville, St. Augustine, St. Petersburg, Tampa, and Jackson, Mississippi. "With the exception of these five city banks each of the closed banks has the same character of assets, these assets practically all arising from agricultural operations and when secured being secured by first or second mortgages on real estate, scattered live stock, farming implements, etc.

"Collateral . . . is being required in order to protect our position with them. Conferences are being had with their officers in an effort to have them remedy their position." By June 1932 liquidations had reduced member banks in the Sixth District to 318, well below the 381 members the Bank opened with in 1914.

Federal Reserve Banks were strict in the collateral they would accept for rediscounts. However, once a bank indebted to its District Federal Reserve Bank failed, the Fed (until Congress created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation in 1934) became the receiver and liquidator of failed member banks. In this role, it encountered all kinds of collateral the failed bank had accepted, a situation which caused the Atlanta Fed to make ledger entries like this one: "Loss, on account of death, of cow, carried in misc. assets acquired thru failed banks—book value, $1.00."

By July 1932 the situation, while grim, seemed to have stabilized in the Sixth District, leading Black to report, "The economic and banking situation has shown little change. Business conditions show little improvement. Confidence has been largely restored in our banks. . . . Fortunately, we have escaped the banking panic that has existed during the past month in the Boston and Chicago districts. . . . We should congratulate ourselves that these effects [lost deposits, cash hoarding, general uneasiness] have been appreciably smaller in our district."

Band-Aid for agriculture

The Depression that followed the Crash of 1929 caused demand for commodities to shrink and prices to fall, which put the cotton economy of the South in much the same bind it faced in 1920-21. True to its mission, the Atlanta Bank moved to support cotton by providing credit. In October 1930 the Atlanta Fed issued a circular that proclaimed, "Our bank has shown its intense interest to be of aid in the orderly marketing of crops. . . . Heretofore we have loaned to member banks 80 percent of the market value of the cotton at the time the loan was made. We are willing now to increase this loan to 90 percent. . . . The purpose of this circular is to emphasize our desire to cooperate to the fullest extent in making available the resources of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta in any proper manner to permit and further the orderly marketing of cotton."

Sadly, the solutions of 1920–21 were ineffectual when the market for cotton failed to revive. By November 1932, after two years of supporting cotton, Black had to report: "Collections have been exceedingly slow with country banks. They have been unable to collect. Cotton that has sold has been limited in quantity and the price low. . . . The result must be a carryover on our part for many of these banks. In each case we are carrying large additional collateral in an effort to protect our position. . . ."

For many of the agricultural banks of the Sixth District there was no way out. "[T]heir cash position is low, their collections exceedingly limited, their assets largely pledged, and before them a year's operation before substantial seasonal collections can be made," Black noted. "[W]e are aiding as far as we can. . . . Some of them can be aided, some of them can pull through, but in my opinion some of them must succumb."

The change in business conditions in the District made its mark on the Atlanta Reserve Bank's own financial status. Earnings on credits to member banks dropped rapidly from $3 million in 1929 to $58,872 in 1934 as interest rates dropped and demand for credit dried up.This trend was partly offset by rising income from a growing stock of U.S. securities the Bank was buying to get earning assets. Still, total earnings dropped from $4.1 million in 1929 to between $1.4 million and $2 million in the following five years. Belt tightening reduced expenses marginally, but net earnings slid from $1.4 million in 1929 to nothing in 1931 and never rose above $325,000 through 1933. Since this was no time to deny member banks their dividends, money was transferred from surplus to meet the dividends in 1931 and 1933. Even paid-in capital began a slow slide after 1929 as member banks were closed or shrank.

All the Reserve Banks were operating at a deficit, Black reported in May 1931. Among its peers (the six smaller Fed Banks), Atlanta's losses were less than Richmond's for the first quarter of 1931, but greater than those of Dallas, Kansas City, St. Louis, and Minneapolis. A committee was appointed to look into staff and salary cuts for the Atlanta Bank. The committee concluded that such cuts would undermine confidence by showing that a Reserve Bank was in trouble. But in December 1932 the board reluctantly passed a 12 percent, across-the-board pay cut, then made revisions in January 1933 to soften the blow for lower-paid employees. Two directors favored larger cuts on the grounds that the Reserve Bank always had tried to maintain parity with commercial bank salaries in the District and draconian pay cuts were the order of the day at many banks in 1932. But even the smaller cuts that were approved were short-lived.

FDR and the bank "holiday"

The month before that December board meeting the nation elected a new president, Franklin D. Roosevelt. Sweeping changes were coming that would radically reconstruct the Federal Reserve System and rewrite the role of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

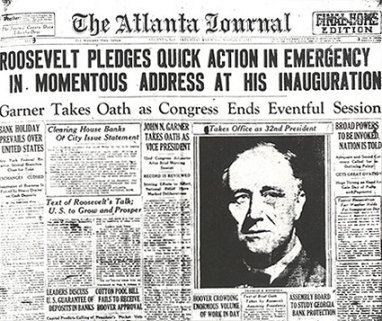

The inauguration of President Roosevelt and the complete collapse of the U.S. banking system were converging on the date March 6, 1933. They arrived almost simultaneously. Bank failures had become a statewide phenomenon. The first banking "holiday" occurred in Michigan on February 14 and closed all of the state's banks. Other states followed. The Sixth District began to fold in March when the banks of Alabama and Tennessee were closed on March 1, the banks of Mississippi and Louisiana on March 2, and the banks of Georgia on March 3. On Saturday, March 4, all banks were closed in the rest of the United States, and one of President Roosevelt's first official actions was to proclaim a national banking holiday from March 6 to March 11, with only temporary, emergency banking services offered. During that week, banks would be sorted out and only sound ones allowed to reopen. In the first six months of 1933, the number of member banks nationwide dropped from 6,816 to 5,606, and in the Sixth District from 323 to 283. Having the liquidity to pay off anxious depositors was crucial to some banks' hopes for reopening, so members pressed to rediscount their illiquid assets.

The banking crisis of the Depression came to a head as Franklin Delano Roosevelt took office on March 4, 1933. |

The activity of the holiday week at the Atlanta Bank is vividly recorded by assistant cashier V.K. Bowman: "The banking holiday arrived! Phoned around 1 a.m., to come to the bank, picking up the two senior secretaries en route. Feelings indescribable! Business halted on dead center. Phones constantly ringing. City bankers crowding Governor Black's office. Plans to make advances to member banks on any asset having value were made. The personnel of the Examination and Accounting divisions were assigned to assist the Credit division in this work. The bank was filled with bank officers from all over the District. Mail sacks, garbage cans, waste baskets, cardboard boxes, anything that would hold and carry notes and collateral were stacked up in the vault, they having been inspected, listed and valued for collateral to advances to be made on request to the respective member banks when they were licensed to reopen." When banks did reopen, withdrawals were light and most collateral was reclaimed within a few weeks, Bowman recalled.

With all banks closed, there was an acute shortage of cash and limited means for making payment, so some communities within the Sixth District, as elsewhere, issued substitutes, called scrip, during the emergency. In Talladega, Alabama, for example, school teachers were paid in scrip, redeemable at a later date, but in the meantime a medium of exchange which could be used to buy groceries. Additional scrip circulated in Talladega in the form of cards on which were stuck 36 three-cent stamps. The cards became spendable money worth $1.08 each.

When Congress established the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) later in 1933, over the strong objections of many bankers, the new agency faced the daunting task of screening state banks to determine which ones were solvent and therefore eligible for insurance. The Reserve Banks lent experienced examiners to the FDIC for this process, according to J.E. Denmark, a Fed bank examiner who was assigned temporarily to the FDIC. In fact, the banking collapse brought new vigor to the whole field of bank examination. The Fed had been conducting routine field examinations of state member banks since at least the early 1930s, but in such examinations, conducted jointly with state bank examiners, the Fed looked at little beyond solvency and asset quality, according to Denmark. But in 1933 the Board in Washington expanded the scope of examinations into something like it is today. Examinations became more rigorous, and the Atlanta Bank had to hire several new examiners to keep up with the work load.

An Atlantan goes to Washington

Roosevelt's frenetic first 100 days were felt particularly in the Atlanta Fed because the nation's new president wanted the Atlanta Bank's governor to come to Washington to head the Federal Reserve Board. In May 1933 Black left for Washington, where his tact and diplomacy no doubt were valuable during the rockiest period in U.S. banking history. But Black, who called his position at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta "the greatest job in the world," was a reluctant national leader. He left Atlanta with the understanding that he would serve in Washington for only a year and then return. The Bank kept his seat open by naming W.S. Johns acting governor. Johns, the deputy governor and former auditor, was a Georgia banker who had joined the Bank's staff in 1919; he directed the Bank until Black's return 15 months later, on August 15, 1934.

Up from the depths

The Depression bottomed out in the Southeast in 1933. Prices on the bellwether cotton began to rise that year. Loans to member banks dropped from $18 million to $8 million in June, and Acting Governor Johns explained why: "On account of the continued increase in the price of cotton, very few of our agricultural member banks are asking for additional accommodation. Many of them are further decreasing their indebtedness to the Reserve Bank, and several have paid their indebtedness in full during the month." By October, improved prices and increasing agricultural support from the federal government were combining to put the Fed out of the cotton financing business. Reported Johns, "On account of the Government's expected cotton financing program, there appears to be a disposition on the part of farmers to hold their cotton, and on account of the improved positions of our agricultural member banks they are able to carry cotton or other commodity loans in their own portfolio and there appears to be no necessity for them to offer this paper to the Reserve Bank."

In fact, once the FDIC insured the deposits of most banks (and all member banks), deposits became stable. For most banks loan demand dried up during the Depression. Thus, once past the crisis of 1933, they had plenty of lending capacity and little need for additional credit. The Atlanta Fed turned to a growing supply of government bonds to provide the meager but consistent income needed to pay its bills.

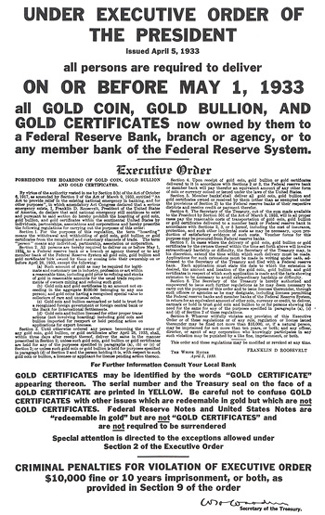

Notice of 1933 announcing the government's recall of all gold. |

The Fed loses its gold

In response to the economic conditions of the Depression, the treasuries of the Reserve Banks were raided by the Roosevelt monetary policy—specifically by the Gold Reserve Act of January 30, 1934, which devalued the dollar by reducing its gold content by nearly half. The act also required the Federal Reserve Banks to surrender their gold to the Treasury (from where it had come in 1914); the Banks were to be paid for the gold with gold certificates. As soon as the President signed the bill, the Secretary of the Treasury demanded the transfer of all gold held by the Reserve Banks—in the case of Atlanta, $7.7 million of gold coin.

The modest upturn in the economy in 1933 and 1934 improved collections from the liquidations that followed the banking holiday. Sixty-two member banks did not reopen, 52 of which owed the Atlanta Bank $11 million, more than its 1934 capital and surplus of $9.9 million. But by January 1934 Johns could report that collections had reduced the debt to $1.3 million and that collateral held by the Bank was more than adequate to cover that amount.

By November 1934 Black, back at his Atlanta post, found that "agricultural conditions in the Sixth District are very good. Farmers are liquidating their current bills and paying on indebtedness contracted in previous years. The citrus crop in Florida will be large and representatives from that State expressed the opinion that, if a fair price is obtained, many old debts will be paid."

Black was hailed as a triumphant son by a District that, like the rest of the nation, believed, in the fall of 1934, that the worst was over. He was much in demand as a speaker. Then, four months after his return, he died of a heart attack on December 19. He was 61. The mantle of leadership passed to Oscar Newton, the Mississippi banker who had succeeded McCord as chairman and Federal Reserve agent. Newton, a circumspect churchman, was regarded by his fellow directors as "a quiet, retiring and very modest gentleman."

| Previous | Next |