Transitioning from Hospitality to Health Care Occupations

Sarah Miller and Pearse Haley

August 28, 2020

2020-10

https://doi.org/10.29338/wc2020-10

Download the full text of this paper (1.48 KB)

The job losses and unemployment claims caused by the COVID-19 pandemic are unrivaled in modern times. Despite record job growth in June and a decline in unemployment, the U.S. economy remains at great risk.1 Although many furloughed workers have returned to their jobs, millions of workers have been laid off permanently.2 Many of the regained jobs were in industry sectors most affected by the initial shutdown, such as bars and restaurants and hospitality and tourism. Since the U.S. Department of Labor's June Employment Situation Summary was released, however, COVID-19 cases have spiked in many states, and the United States as a whole has seen record numbers of new cases. Local and state governments have slowed or paused the reopening of businesses in response to the surge in cases, sending many workers in these recently recovering industries back home.3

The threat of increased job losses and unemployment claims due to industry shutdowns is compounded by the expiration of CARES Act–extended unemployment relief of $600 per week on July 31, pending an extension by Congress, as well as the complete or near exhaustion of Paycheck Protection Program loans by many employers.4 Recovery forecasts have worsened in response to this uncertainty, with the service industry facing the gloomiest outlook.5 Job losses in the service industry have disproportionately affected Black, Asian, and Hispanic workers as well as women, particularly single mothers and low-income workers.6 These workers are more likely to earn low wages and less likely to receive health insurance or paid leave from their employers. They often serve as the sole or primary earner for their households.7 This disproportionate impact, combined with continued uncertainty surrounding economic recovery and extension of government relief, have placed service industry workers in a precarious position. Typically seen as less skilled, service workers lack the time and resources necessary to enter retraining and reskilling programs in pursuit of new employment.

Health care employment as a solution

The increased demand for health care occupations may offer vulnerable service workers an opportunity for economic relief before they exhaust unemployment benefits and face housing and food insecurity. Many of the most in-demand jobs are in the health care sector and offer wages at or above those in most service industry jobs.8 We identify what potential health care jobs are available to workers in both the restaurant and hotel industries based on overlapping skills and workplace activities. Using data from the U.S. Department of Labor's Occupational Information Network (O*NET) and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics' Occupational Outlook Handbook (OOH), we identify health care jobs that would likely be obtainable by workers at entry, mid-, and advanced levels of both pay and skills.9 The selected health care occupations meet the criteria for "lifeboat jobs," meaning they require little to no retraining or reskilling while also providing the opportunity for unemployed workers eventually to return to their previous income level.10

Our selection criteria for health care careers that would offer reasonable pathways for COVID-19 affected jobs in the hospitality sector include:

- Occupations are accessible with no more than a high school diploma for entry and midlevel occupations, less than a bachelor's for advanced/management.

- There is significant overlap in workplace activities and skills with selected service occupations.

- The technical skills gap is narrow and critical skill development can be obtained on the job.

- Occupation offers a similar median wage, a pathway to a higher-paying health care occupation, or both.

- Occupation is either in high demand or offers skills and experience necessary to enter a high-demand occupation.

Transportable skills and lifeboat jobs

Service workers possess many baseline skills that are transportable across a wide range of industry sectors and organizational structures.11 These transportable skills can allow workers to build bridges to new roles and industries such as health care. These skills are broader and more difficult to measure than technical skills, causing them to be undervalued in many job postings.12 Consequently, unemployed service workers facing the exhaustion of their benefits may believe they do not meet the job requirements due to the higher than average demand for technical skills in health care job postings.13 Furthermore, workforce intermediary agencies and other reemployment-focused efforts might also underestimate the relative transferability and meaningfulness of skills developed within the hospitality sector and fail to consider a transition to the health care field as a short path to a new career for their participants.

To better analyze the overlap in transportable skills between service and health care occupations, we use O*NET's descriptors for workplace activities rather than basic skills. Workplace activities show what workers actually do on the job, allowing for more concrete description of skills and better estimation of how transportable these skills are across industries. For example, as opposed to focusing on "communication" as a skill set, we examine the workplace activity that describes how the communication skill is applied through job tasks to allow for a deeper illustration of how these workplace activities and skill may align, even though the working environment is markedly different.

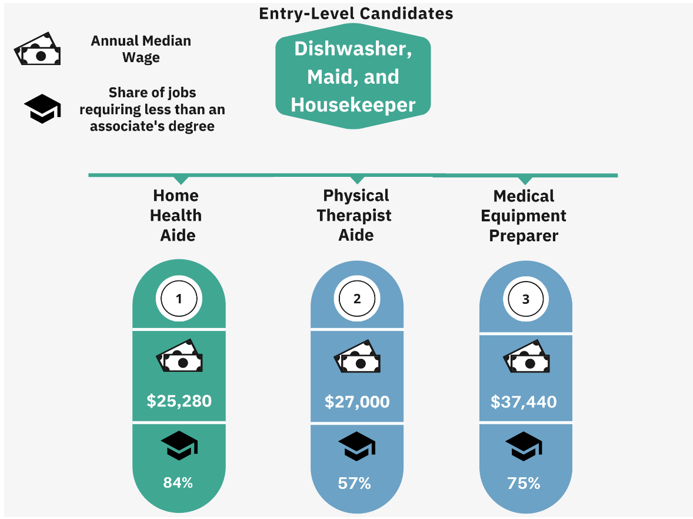

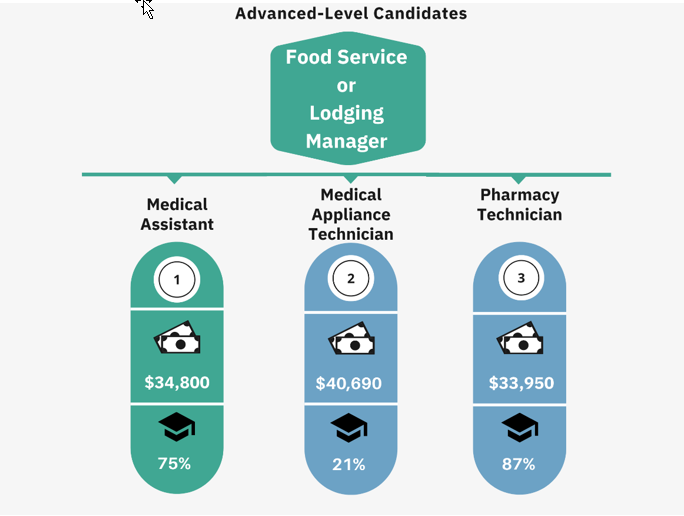

We chose food service and hospitality positions at the entry, mid-, and senior levels as our starting point, because they are in two of the hardest-hit industry sectors and have significant skill overlap to destination pathways in the health care field. We then apply criteria stated above to identify pathways to a number of health care careers in demand at each skill level. Chart 1 shows our selected service occupations for each skill and experience category and the three health care occupations we identify for each. We select one primary position, highlighted in green, based on the criteria listed above.

Chart 1

Potential Health Care Pathways

Sources: National Center for O*NET Development, Health Care and Social Assistance Industry, Accommodation and Food Services Industry, O*NET OnLine

We did not select some candidate occupations, such as certified nursing assistant, due to certification requirements while others, such as medical equipment technician, required a significant increase in technical skills that would not allow service workers to transition to these positions quickly when they need more immediate employment options. Our selected occupations consist of home health aide and medical assistant, which LinkedIn identified in May as among the 15 most in-demand health care occupations based on job postings; we also selected medical secretaries. See the table for the top 15 list of health care jobs. We believe that all three occupations offer clear pathways to service workers toward immediate employment with the potential for long-term advancement and greater earnings.

Most In-Demand Health Care Jobs

- Pharmacy specialist

- Home health aide

- Home health nurse

- Radiology technologist

- Certified nursing assistant

- Speech language pathologist

- Medical doctor

- Occupational therapist

- Patient care assistant

- Licensed practical nurse

- Case management nurse

- Pharmacist

- Registered respiratory therapist

- Emergency medical technician

- Medical assistant

Source: LinkedIn, May 2020

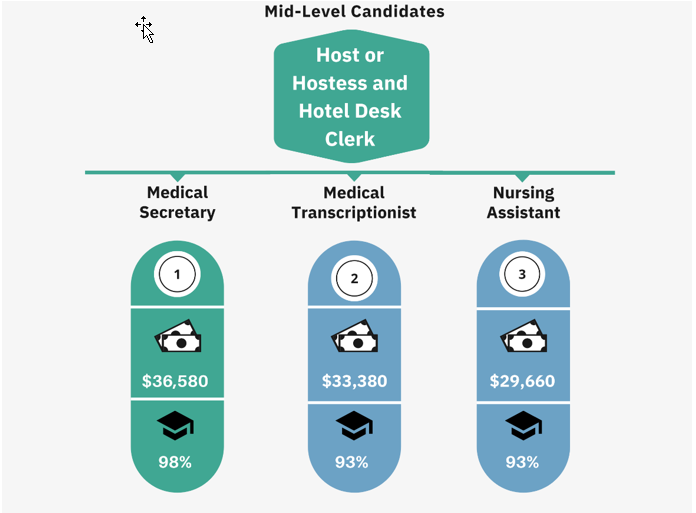

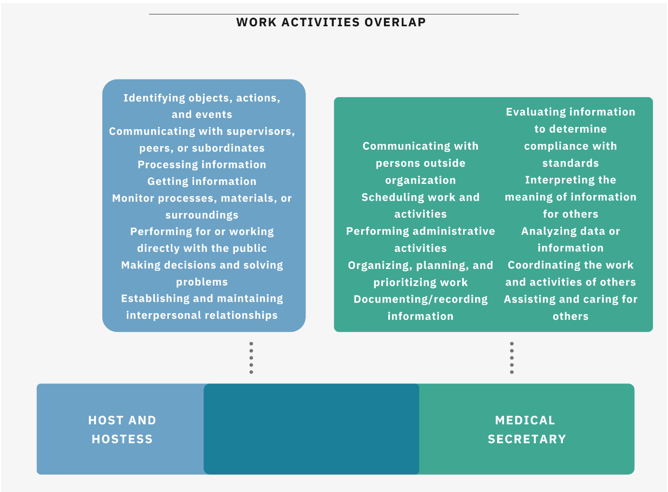

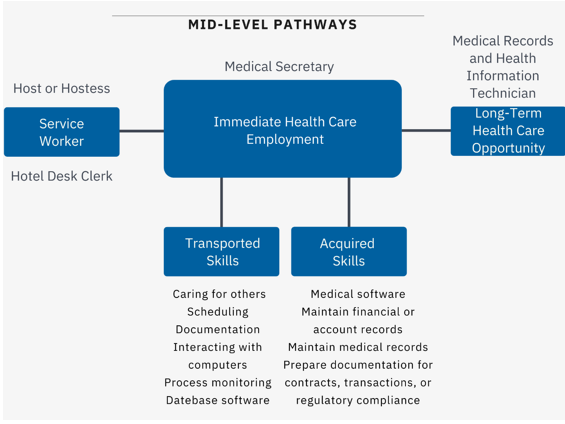

We compare the health care work activities and technical skills that service workers possess with those they lack (skills they have versus those they need). We consider both the actual overlap as well as missing activities and skills that service workers would likely be familiar with despite not indicating their usage in O*NET survey responses. For example, a host and hostess lacks more workplace activities required of a medical secretary than they possess; see chart 2. A closer examination of medical secretary workplace activities reveals, however, that skills and activities including "assisting and caring for others, interacting with computers, documenting/recording information, and communicating with persons outside organization" do not appear in O*NET workplace activities for a host and hostess. Regardless of their absence in the O*NET data, these are daily activities we can reasonably expect most hosts and hostesses to carry out on a regular basis.

Chart 2

Work Activities Overlap

Sources: National Center for O*NET Development, Health Care and Social Assistance Industry, Accommodation and Food Services Industry, O*NET OnLine

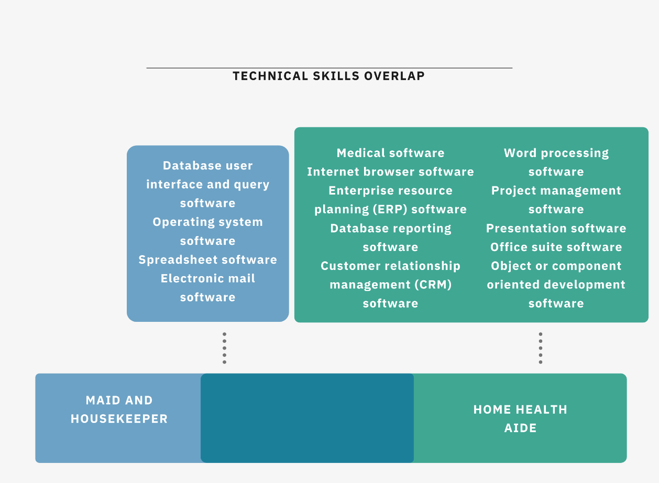

We apply the same reasoning to the technical skills gap; see chart 3. The gap between entry-level service jobs and a home health aide includes the ability to use internet browsers, email, and word processors. While service workers do not report using these skills on the job, we again believe it is reasonable to assume that many dishwashers and maids and housekeepers will be familiar with most if not all of these tools—either through workplace practices or personal use. We additionally presume that skills of this nature these workers might not possess can be easily taught and picked up quickly on the job. When we remove these more basic technical skills, the gap narrows considerably across all service categories.

Chart 3

Technical Skills Overlap

Sources: National Center for O*NET Development, Health Care and Social Assistance Industry, Accommodation and Food Services Industry, O*NET OnLine

We believe that the overlapping work activities are sufficient to bridge the gap created by more specialized skills such as medical project management software. The primary responsibility of a home health aide is to provide quality, personalized care at patients' homes or care facilities. While entry-level service workers may not have experience with the specific tools that home health aides use to document the status of patients, they do have experience in recording information, maintaining work schedules, and caring for others. This applied context is essential to the determination of whether workers possess sufficient translatable skills to outweigh any technical gaps between other occupations.

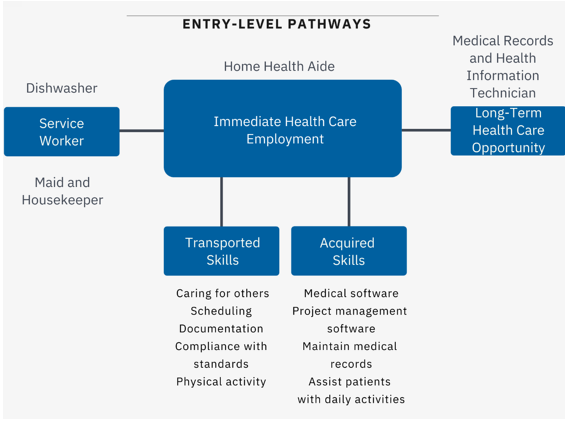

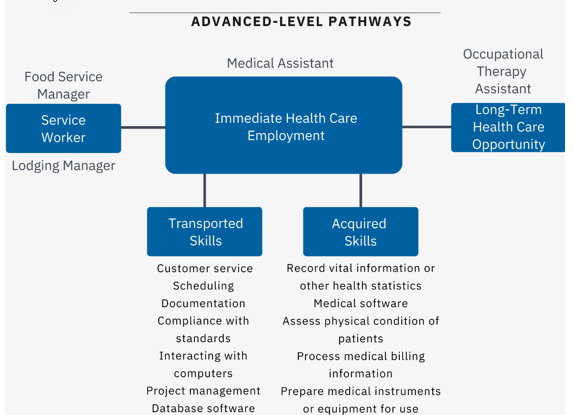

Enabling long-term cross-industry pathways

Vulnerable service workers must consider immediate employment while also preparing for longer-term economic realities due to uncertainty around COVID and its lasting effects. Chart 4 shows the transportable skills that workers can use to access immediate employment as well as the key skills they will gain that can open doors to health care occupations that offer greater long-term self-sufficiency. By leveraging their baseline skills, service workers can gain crucial short-term relief while also giving themselves greater future economic opportunity. The health care sector has demand for workers at entry-level positions that offer on-the-job training that can grant access to more stable employment. Displaced workers then have the option of returning to the service industry should sufficient recovery occur or pursuing a career pathway in health care.

Chart 4

Service to Health Care Pathways

Sources: National Center for O*NET Development, Health Care and Social Assistance Industry, Accommodation and Food Services Industry, O*NET OnLine

Policy recommendations

This framework offers potential solutions for workers facing the exhaustion of unemployment benefits or who are currently employed but vulnerable to COVID-19 related shutdowns. We recommend a more detailed inventory of transportable skills from industries severely affected by the pandemic to the most accessible health care occupations with high demand. We also suggest increased collaboration between workforce development agencies, industry leaders, professional associations, and policymakers in order to create a picture of health care demand and employment requirements that reflects regional differences. Finally, we propose the allocation of funds for short-term training programs that would provide access to a wider range of health care occupations.

Mapping health care pathways

Karen Kimbrough, chief economist at LinkedIn, stresses that in order to "address the unprecedented levels of unemployment we're seeing in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, leaders must quickly make major decisions around how we get people back to work, and reskill people for roles that our economies need both right now and in the future." Insights gained from job postings and worker surveys can "uncover short-term transitions that workers whose roles have been impacted by the pandemic—especially in the hard-hit service industry—can make into areas with high demand—like health care support jobs—with relatively light investment into training."

Job postings more accurately represent what employers want than they do what workers actually do on a daily basis. By combining data from worker surveys with job postings data, researchers and policymakers can create potential pathways to health care that meet the needs of employers in a way that is more accessible to workers without previous health care experience. We recommend developing a crosswalk between baseline skills and workplace activities along with more detailed descriptions of technical skill requirements and the potential for workers to learn them on the job. This approach will yield a fuller picture of what health care occupations are immediately attainable to workers from other industries.

Interagency and industry collaboration

This type of mapping will require collaboration between professional associations, workforce development agencies, training providers, funders, and employers if it is to meet the pressing needs of America's workforce in a timely fashion. This collaboration could focus on identifying opportunities to fund and provide increased on-the-job training and certification as well as balancing the need for immediate employment and staffing of health care occupations with long-term employment as economic recovery begins. Health care has a high turnover rate that has been exacerbated by the pandemic, and efforts to fill positions with unemployed workers must avoid accelerating that turnover.

Focus on competencies in job design and advocate for skills-based hiring

Beyond just the health care sector, workforce intermediaries must work with their partner employers to analyze job function and highlight key competencies and workplace activities essential to the success of the position. Many job descriptions lack key skills or competencies and focus on the job task, not necessarily the full complexion of the position with the core attributes that would help workers and job placement efforts better align prior experiences with new career pathways. Designing jobs, and job descriptions, in a way that highlights fundamental components employers seek from their incumbent workforce and future talent allows for easier transition of skills in a promotional path and in transitional career moves from one industry to the next. Starting with a clear understanding of what an employer needs from the position lends itself to a new, skills-based approach to hiring. Ultimately, we hope to see skills-based hiring emerge as a standard practice moving into recovery and reopening. The existence of a credential should not be the only metric to assess worker fitness for a position. This allows more flexibility in recruitment and development of labor pools and would create a more equitable recovery.

This increased flexibility will be crucial to assisting populations disproportionately affected by the pandemic. Kimbrough notes that, "women have been among the hardest hit by this recession, and one of the single biggest boosts we can provide to bring them back into the workforce is offering more flexibility." The in-demand health care occupations that we highlight "offer, first and foremost, more flexible training and upskilling options via online learning, and also more flexible scheduling than many of the service-sector roles that they've lost." By offering a variety of training and scheduling options, these occupations make it easier for unemployed workers to leverage prior skills to make cross-industry transitions.

Leverage prior skills to build education and on-the-job training plans

Workforce intermediaries could consider prior experiences on the job to help develop targeted individual learning plans for their participants and as a way to incentivize on-the-job training opportunities. By recognizing, and valuing, prior experiences, as opposed to simply the highest level of credential, the workforce system can expand the opportunities available to the participants seeking to get their foot in the door into a new career field or reemploy quickly into a higher-paying, in-demand field. Additionally, mapping prior experiences creates a realistic difference between competencies job seekers have and those they would need to obtain during on-the-job proposals to industry where on-the-job funding would offset employer-paid wages while critical skills are developed.

Sarah Miller is a senior adviser and Pearse Haley is a research analyst I, both at the Center for Workforce and Economic Opportunity.

_______________________________________

1 Tappe, Anneken. (2020, July 2). "The US Economy Created 4.8 Million Jobs in June. But That's Not the Whole Story."

2 Lane, Sylvan. (2020, July 19). "Jobless Claims Raise Stakes in Battle over COVID-19 Aid."

3 Mutikani, Lucia. (2020, July 2). "U.S. Job Growth Roars back, but COVID-19 Resurgence Threatens Recovery."

4 Iacurci, Greg. (2020, July 9). "Job Losses Remain 'Enormous': Coronavirus Unemployment Claims Are Worst in History."

5 Craven, Matt, Linda Liu, Matt Wilson, and Mihir Mysore. (2020, July 9). "COVID-19: Implications for Business."

6 Catalyst. (2020, July 22). "The Impact of Covid-19 on Job Loss."

7 Ross, Martha and Nicole Bateman (2020, March 19). "COVID-19 Puts America's Low-Wage Workforce in an Even Worse Position."

8 LinkedIn, May 2020.

9 Council for Adult and Experiential Learning. (2017). "Retail to Careers in Adjacent Industries: Common Skills for Employability and Pathways to Advancement."

10 Burning Glass Technologies. (2020, May). "Filling the Lifeboats: Getting Americans Back to Work in the Pandemic."

11 Burning Glass Technologies. (2019, February 20). "The Power of Transportable Skills: Assessing the Demand and Value of the Skills of the Future."

12 Ibid.

13 Burning Glass Technologies. (2015, November). "The Human Factor: The Hard Time Employers Have Finding Soft Skills."