Older Workers Face New Risks because of the COVID-19 Recession

Siavash Radpour, Aida Farmand, and Teresa Ghilarducci

September 3, 2020

2020-11

https://doi.org/10.29338/wc2020-11

Download the full text of this paper (661 KB)

For the large cohort of older workers, the significant difference between the COVID-19 recession and previous ones is the combined effect of the economic recession and the health risks of the COVID-19 outbreak. Older workers are facing the high health risks of working during a pandemic, on the one hand, as well as the risk of losing their jobs, on the other hand, which can lead to significantly lower wages in the future or even involuntary early retirement.

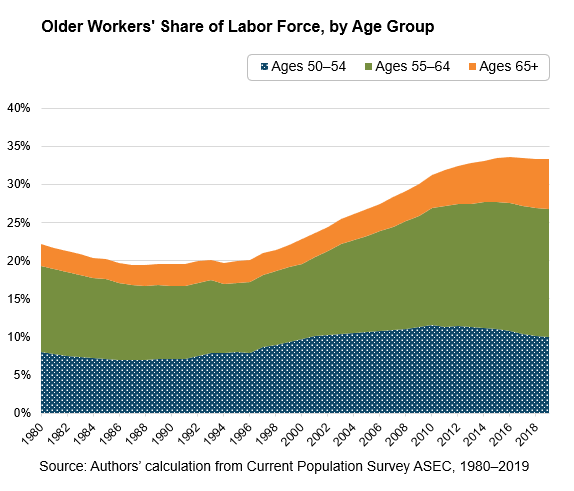

Older workers are a substantial and growing share of the U.S. labor force. The share of people working or looking for work who are 50 or older is more than 33 percent, up from 20 percent in 1990 and 29 percent in 2008 (see the chart). Part of this trend is demographic: the 75 million-strong baby boomer generation began turning 55 in 1999, leading to a rapid rise in the share of older workers. At the same time, older people are working longer because they have to—their retirement income is less secure, and they work to supplement their low pensions (if they have one), savings, and Social Security benefits.1

The demographic shift in the labor market has serious policy implications for the COVID-19 pandemic and recession, including health and safety standards, retirement reforms, implementation of anti-age discrimination laws, and expansion of Social Security benefits.

Older workers face new health risks

Older workers are more vulnerable to illness and to the deadly and debilitating effects of COVID-19 because people's immune systems weaken naturally by aging2 and preexisting conditions increase with age: up to 86 percent of people between 55 and 64 have some type of preexisting condition.3 Over a third of workers in occupation categories with high contact intensity are over 50 (see the table).

Paid sick leave is a public health issue. It keeps people who are ill home and prevents infection from spreading.4 In addition, paid sick leave indicates employers' attention to employees' health and safety. In 2018, about 40 percent of workers over 50 worked for employers that did not provide paid sick leave.5 The chance of working for employers providing paid sick leave for the 6.8 million older workers in high-risk frontline jobs is lower than for younger workers in the same jobs.

Share of Older Workers (Age 50+) in Some of the Occupations with Highest Contact Intensity

| Occupation | Proximity Index | Share of Older Workers (50+) |

|---|---|---|

| Barbers, hairstylists, and cosmetologists | 92.17 | 36% |

| Occupational therapy and physical therapist assistants and aides | 90.50 | 30% |

| Home health and personal care aides | 90.25 | 38% |

| Therapists and social workers | 88.09 | 33% |

| Health technologists and technicians | 82.73 | 33% |

| Health care support occupations | 80.20 | 33.4% |

| Teachers | 79.54 | 33.4% |

Source: Authors' calculations from Current Population Survey (May 2020); occupational categories and physical proximity index from Leibovici, Fernando, Ana Maria Santacreu, and Matthew Famiglietti (2020), "Social Distancing and Contact-Intensive Occupations," On the Economy, St. Louis Fed

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) made paid sick leave available to many workers, but many employers were exempted and the coverage is limited. Furthermore, while some employers not providing paid sick leave (indicating worker health and safety is a low priority) are now required to offer it, they may not provide other necessary means to make the workspace safe for older workers. Between April and June, the U.S. Department of Labor's Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) released several guidelines for employers on preventing workers' exposure to the virus, preparing the workplace for COVID-19, and reopening and returning to work. Unlike standards and regulations, these guidelines are "advisory in nature, informational in content" and "create no new legal obligations." Worker advocates argue that there is a shortage of safety measures and protective gear, and the existing standards are not enough to keep workers safe.

Unemployment, reemployment, and involuntary retirement

Although the COVID-19 recession differs from previous recessions, one fact remains constant—recovery from a recession is persistently slower and less successful for older workers. Displaced older workers are more likely to experience a layoff and longer spells of unemployment in a recession. When older workers do find jobs, they usually pay considerably less than their previous jobs. Older workers face high risks of getting sick at work, which can lead to permanent disability or even death. They also risk losing their jobs and having their pay cut if not pushed to involuntary retirement.

Many older workers never recovered from the economic aftermath of the Great Recession; they took low-paying, part-time occupations or became gig workers.6 Now, those same occupations (such as warehouse workers, ride-share drivers, and home health aides) are facing higher unemployment rates, health risks, or both, pushing those underemployed workers into an even more fragile economic position.

Younger workers usually suffer the highest increases in unemployment rates during recessions.7 At the peak of unemployment caused by the COVID-19 recession in April, the unemployment rate for workers under 25 exceeded 25.7 percent, over twice the unemployment rate for workers 25 to 54. Older workers, in contrast, are usually less likely to lose their jobs during a recession since their seniority protects them.

However, unlike the aftermath of the Great Recession and as a result of the COVID-19 recession, the unemployment rate for workers 55 and over was significantly higher than for workers 35 to 54. The COVID-19 recession heavily affected women 55 and over, whose unemployment rate increased by 12.2 percentage points between March and April (from 3.3 percent to 15.5 percent), compared to an increase of 8.7 percentage points for men 55 and over (from 3.4 percent to 12.1 percent). While some workers returned to the labor force and found new jobs in May, the labor force participation of older workers further declined, signaling a longer recovery for those workers.

Of concern is the possibility that the greater health risk for older workers and the associated increase in costs of health and safety measures as well as the cost of health insurance—higher for older workers—will discourage employers from hiring them when the economy recovers. On average, insurance reimbursements for workers aged 55 to 60 who have private health insurance at work cost employers about twice the reimbursement for workers aged 30 to 35.8 The higher cost of health insurance is associated with higher unemployment, lower wages, and lower chances of having employer-sponsored health insurance.9 The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to widen the gap in safety and health care costs between younger and older workers, putting older workers at an even more disadvantageous position in the labor market.

Job loss often forces older workers into involuntary, early retirement.10 We found that from 2008 to 2014, at least 52 percent of retirees older than 55 left their last job involuntarily—the result of job loss or declining health. Many older workers will not be able to return to the labor market when it recovers. Instead, early retirement means most of these retirees will have less retirement savings to live on and will face a decline in their living standards or deprivation as they age.

Most working families nearing retirement age were not prepared for retirement even before the crisis. The median working household nearing retirement (with the head of household 55 to 64) had only $43,000 in retirement savings in 2016, far from enough to provide the household with sufficient income to maintain their living standards. For these older workers, postponing retirement and working longer seemed to be the only option. Early retirement due to the COVID-19 recession, however, made the situation worse. Those who were counting on working longer to make up for the lack of retirement assets find it to be even less feasible than before the recession and will be pushed to early retirement. But for those workers who did not have sufficient retirement assets to begin with, early retirement only means claiming Social Security benefits earlier and receiving significantly lower benefits for the rest of their lives.

Of course, not all older workers have the same risks. Knowledge workers and people who do most of their work on computers may not lose their jobs but instead suffer pay cuts. Around 7.6 million older workers (or 14 percent) in these occupations such as corporate executives, information technology managers, financial analysts, accountants, and insurance underwriters do not have a particularly high risk of unemployment or sickness. But older workers are overrepresented in only one occupational category: the legal sector. Unlike many tech companies, which continue to hire more people even in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis, large and midsize law firms responded to economic pressures caused by the pandemic with pay cuts, layoffs, and lower partner payouts.

Policy recommendations

We offer the following policy recommendations to help mitigate the risks facing older workers.

Better protective standards: Not issuing workplace standards is shortsighted and puts workers—especially older workers—at risk. OSHA needs to expand regulations and standards and step up inspection and enforcement to facilitate a healthy recovery without further waves of infection and frequent shutdowns and quarantine orders, not to mention preventing illness and death.

Extended unemployment benefits for older workers: Older workers need longer unemployment benefits and enhanced benefits to enable them to stay home. Even if older workers are looking for a job, it will take them longer than their younger counterparts to find a new position. Extended unemployment benefits will allow older workers to stay healthy and look for a safe job during recovery.

Lower the Medicare age and make it the primary insurance: Many vulnerable older workers who lost their jobs also lost their health insurance at the worst possible time during a pandemic. Lowering the Medicare age to 50 will enable these workers to stay safe and have access to medical care they need. Forced retirement before Medicare age will rise as a result of higher health insurance costs. Lowering the Medicare age and making it the primary insurance will also lower the cost of hiring older workers and make it easier for them to find employment.

It's not just older Americans who would be helped by lowering the Medicare age. Covering more workers under Medicare helps the program in two ways. One, if the older population are not insured, they cost more when they eventually join Medicare at age 65.11 Adults over 50 who do not have health insurance, especially those with cardiovascular disease or diabetes, have worse health outcomes and use more health services than Medicare beneficiaries who had insurance before they came into the program. Because chronic diseases are prevalent and insurance coverage is often unaffordable for older uninsured adults, the Medicare system is costlier per person than it would be if people had continual insurance before they turned 65.

Stronger anti-age discrimination laws: While older workers experienced lower unemployment rates relative to younger workers, workers 55 and over were more likely to lose their jobs due to the COVID-19 pandemic and recession. This indicates that employers may be averse to hiring older workers who are more vulnerable during the pandemic and may require additional protective measures. Stricter antidiscrimination laws are necessary to help older workers find employment during and after the pandemic. The research has proven the effectiveness of antidiscrimination laws at both federal and state levels in combating age discrimination and increasing employment of older workers.12 However, in 2009 a decision by the U.S. Supreme Court reduced the effectiveness of the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA), the federal act that protects against age discrimination. The ruling increased the burden of proof by requiring the worker to show that age was not only one of the factors considered by the employer, but the deciding factor that led to the employer's discriminatory decision.13 Congress could address this problem by fixing the language of ADEA and make any discrimination motivated by age illegal, which would provide even stronger protections for older workers.

Higher Social Security benefits: Many retirees are going to claim Social Security benefits at an earlier age or miss out on their contributions due to unemployment, while lower average earnings could bring down their benefits. Congress could raise Social Security benefits to mitigate these negative effects of the COVID-19 recession, which can affect those people forced into retirement for life.

There are so many ways COVID-19 has devastated and disrupted lives and the labor market: the cascade of older worker unemployment, newly dangerous workplaces, and earlier-than-planned retirements—like so much else in this pandemic—mean those who were already marginalized and vulnerable will suffer more than others. Federal and state governments can accelerate and revive labor market interventions to help displaced older workers and keep them on the job. Strengthening workplace safety standards to protect those in contact-intensive and frontline work, lowering the age of Medicare to make hiring older workers cheaper for employers, and updating anti-age discrimination laws are policies that could help older workers. These policies could help keep older people working and encourage employers to hire them. Meanwhile, displaced older workers need income support during the recession.

A vaccine could help defeat the health danger from COVID-19. In order to defeat the economic and equity danger, the country needs swift and focused policies.

This article is part of the Leading Workforce Resurgence Series. The views expressed are the authors' and do not necessarily represent the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta or the Federal Reserve System.

Siavash Radpour is the Retirement Equity Lab associate research director at the Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis (SCEPA) at the New School, Aida Farmand is a research associate at SCEPA at the New School, and Teresa Ghilarducci is the Bernard L. and Irene Schwartz Professor of Economics at the New School for Social Research and the director of SCEPA.

_______________________________________

1 Ghilarducci, Teresa and Siavash Radpour (2019). "Older Worker Exploitation: Magnitude, Causes, and Solutions." Generations 43: 3: 6–10.

2 Perrotta, Fabio, Graziamaria Corbi, Grazia Mazzeo, Matilde Boccia, Luigi Aronne, Vito D'Agnano, Klara Komici, Gennaro Mazzarella, Roberto Parrella, and Andrea Bianco. (2020, June). "COVID-19 and the Elderly: Insights into Pathogenesis and Clinical Decision-Making." Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 1–10. Advance online publication.

3 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. (2011, January). "At Risk: Pre-Existing Conditions Could Affect 1 in 2 Americans."

4 Because of the significance of paid sick leave for public health, the Centers for Disease Control keeps the paid sick leave statistics.

5 Ghilarducci, Teresa and Aida Farmand. (2020). "Older Workers on the COVID-19-Frontlines without Paid Sick Leave." Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 32:4–5: 471–476.

6 Johnson, Richard. (2012). "Older Workers, Retirement and the Great Recession." Stanford, CA: Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality.

7 Bell, David N.F. and David G. Blanchflower. (2011). "Young People and the Great Recession." Oxford Review of Economic Policy 27: 2: 241-67.

8 Burtless, Gary. (2017). "Age Related Health Costs and Job Prospects of Older Workers." Working Paper. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution; and Munnell, Alicia H. and Gal Wettstein. (2020). "Employer Perceptions of Older Workers–Surveys from 2019 and 2006." Available at SSRN 3562708.

9 Bailey, James. (2014, August 19). "Who Pays the High Health Costs of Older Workers? Evidence from Prostate Cancer Screening Mandates." Applied Economics 46: 32: 3931–3941.

10 Miller, Mark. (2020, June 26). "A Pandemic Problem for Older Workers: Will They Have to Retire Sooner?" New York Times.

11 McWilliams, J. Michael, Ellen Meara, Alan M. Zaslavsky, and John Z. Ayanian. (2007, December 26). "Health of Previously Uninsured Adults after Acquiring Medicare Coverage." Journal of the American Medical Association 298: 24: 2886–2894.

12 Neumark, David and Joanne Song. (2013). "Do Stronger Age Discrimination Laws Make Social Security Reforms More Effective?" Journal of Public Economics 108: 1–16.

13 McLaughlin, Joanne Song. (2019). "Age Discrimination Laws, Physical Challenges, and Work Accommodations for Older Adults." Generations 43:3: 59–62.