Discontent, Occupational Change, and the Roles Workers Are Leaving amid the Great Resignation

Nye Hodge

September 28, 2022

2022-02

https://doi.org/10.29338/wc2022-02

Download the full text of this paper (179 KB)

Workers are dissatisfied with the world of work and are holding out for flexible and worker-centric opportunities. The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Center for Workforce and Economic Opportunity (CWEO) has been hosting conversations with workers who have expressed displeasure with on-the-job treatment from both customers and management, inflexible work schedules, poor work-life balance, inability to work remotely or with a hybrid schedule, inadequate pay and benefits, limited opportunities for growth and training, and pay raises that are not keeping up with inflation. In fact, the Pew Research Center found low pay, limited opportunities for career growth, poor workplace culture, and childcare issues among the top four reasons workers left their jobs in 2021. Online therapy company TalkSpace says that 53 percent of workers are burned out and 46 percent find work too stressful. Workers have been expressing their discontent by quitting, retiring early, staying unemployed longer, and switching jobs. A larger share of workers are even quitting to start their own businesses, and a larger share of retirees, who normally return to work in some capacity, are staying out of the labor force.

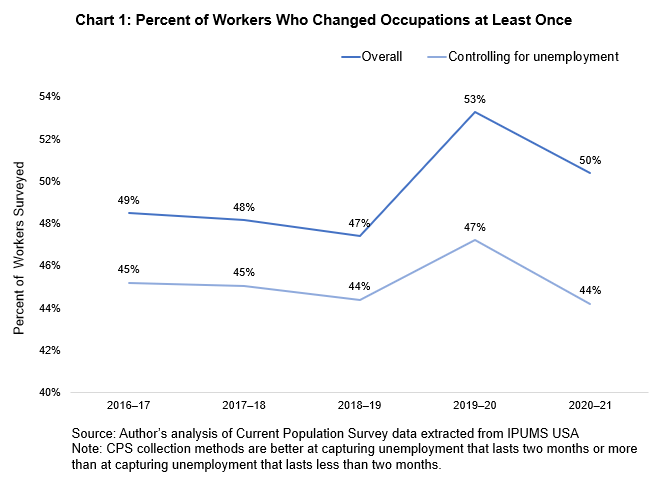

The author used Current Population Survey (CPS) microdata to determine whether worker discontent is resulting in an increased rate of occupational change and to find which occupations workers are leaving. An occupational change is not simply a job change—it is a change to a new line of work. The data also indicate that workers are reevaluating their participation in the labor market. At the outset of the pandemic, 53 percent of workers surveyed had more than once changed occupations from 2019 to 2020 (chart 1), a 6-percentage point increase from the previous year. Before the pandemic, the trend was virtually flat. The percentage returned to the prepandemic levels in the following survey period, 2020–21, but only when controlling for unemployment (chart 1). In fact, workers’ interactions with unemployment remain at postpandemic highs. The findings in chart 1 suggest that workers are not currently switching occupations at an outsized rate (within a one-year period) but are taking longer to reexamine their interaction with or place in the labor market.

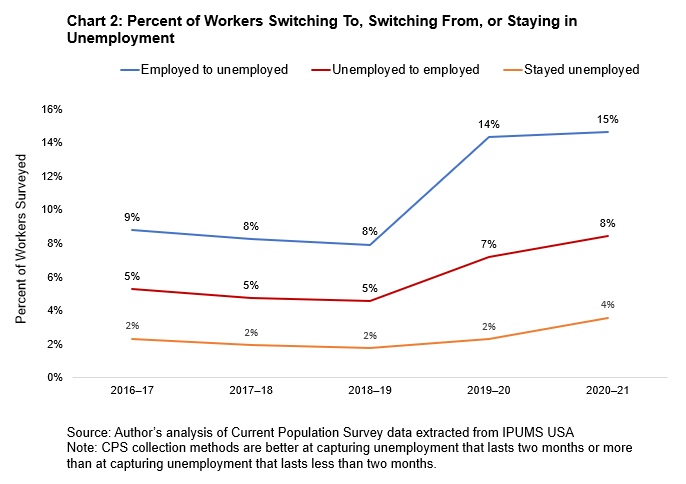

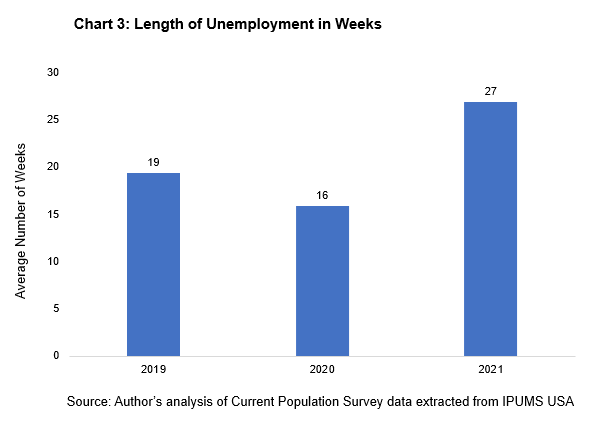

Chart 2 illustrates the percentages of workers switching to, switching from, or remaining in unemployment within one-year periods. All three trends remain at pandemic-era highs. The percentage of workers surveyed who switched from employed to unemployed (blue line) almost doubled. From 2018 to 2019, 8 percent of workers switched from employed to unemployed. That number jumped to 15 percent of workers switching from 2020 to 2021. More workers are also switching from unemployed to employed (red line) than before the pandemic, but the rate of change did not keep pace with the increased rate of workers becoming unemployed. The gap between the blue and red lines widened significantly, moving from 3 percent in 2018–19 to 7 percent the following period, and it persisted in 2020–21. The green line shows that in the last survey period, 2020–21, twice as many workers stayed unemployed from one year to the next compared to the prior periods. A further indication that workers are taking a stand against intolerable and stressful work culture is the length of time workers are remaining unemployed, despite the tight labor market and that there are roughly two job openings for every unemployed person. The average length of unemployment was 27 weeks in 2021, which was two months longer than in 2019 (chart 3).

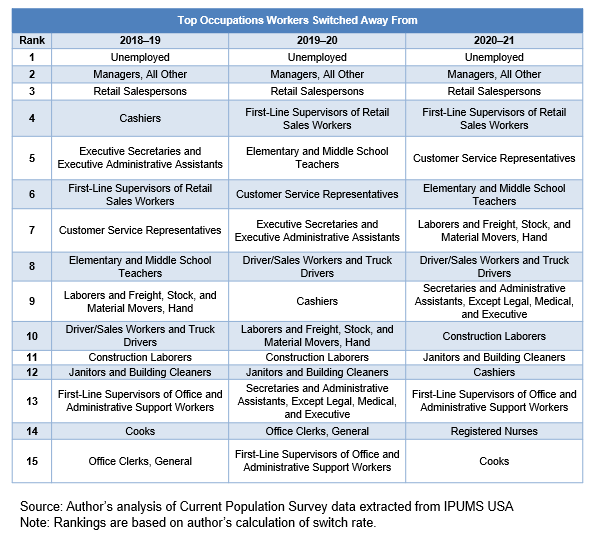

An article in the Harvard Business Review describes a study that found that most jobs going unfilled are location-based, frontline jobs in health care, hospitality and leisure, retail, manufacturing, and transportation and warehousing. The authors analyzed CPS data and found that these fields are usually among the top fields with high turnover, but they note some pandemic-era caveats. Virtually all the occupations in the following table are place-based. Retail occupations are near the top of the lists across all three periods, and other essential occupations that bore the brunt of pandemic work moved up in rank. Notably, for the first time, registered nurse became a top occupation that workers left during the 2020–21 period. The journal Critical Care Nurse recently published a report indicating that working conditions and job satisfaction has diminished for nurses. The study found that only 40 percent of nurses were very satisfied with their work in 2021, down from 62 percent in 2018. The job of elementary and middle school teacher also crept up the list, moving to fifth place in 2019–20, then sixth place in 2020–21, which is up from eighth place in 2018–19, a further indication of the worsening teacher shortage and the attempt across America to get more teachers in front of students.

What CPS data do not tell us is who the employers are that workers are switching from or avoiding. The data also do not capture when workers change jobs within the same occupation. Rather, it only captures when workers change occupations or industries, or become unemployed or employed. In addition, respondents are only surveyed from one year to the next then are never surveyed again, hindering the ability to analyze respondents over the long term.

Workers are emerging from the pandemic with a new sense of value and are not so keen to return to the way things were. If employers want to attract and retain workers, it would be to their benefit to reflect on their culture and what they can offer their workers. Employers should also find ways to grow their prospective talent pools by creating pipelines for diverse groups of workers, implementing skills-based hiring practices, and dropping unnecessary degree and credential requirements.

A report from the Burning Glass Institute found that employers are beginning to omit unnecessary degree requirements. According to Forbes, the rate of employers embracing skills-based hiring accelerated during the pandemic. This situation has created a unique opportunity for workforce intermediaries to help get dissatisfied workers back into the workforce with employers that are worker-centric by leveraging existing skills and experience. McKinsey, in partnership with the Rework America Alliance and the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, developed a job progression tool that maps skills-based pathways to better paying jobs based on a worker’s current or most recent occupation.