What is the state of the Southeast's pandemic economy?

There is no single answer. Rather, there's a patchwork of many economies feeling increasingly varied effects of the coronavirus pandemic, depending mainly on industry, location, and population density.

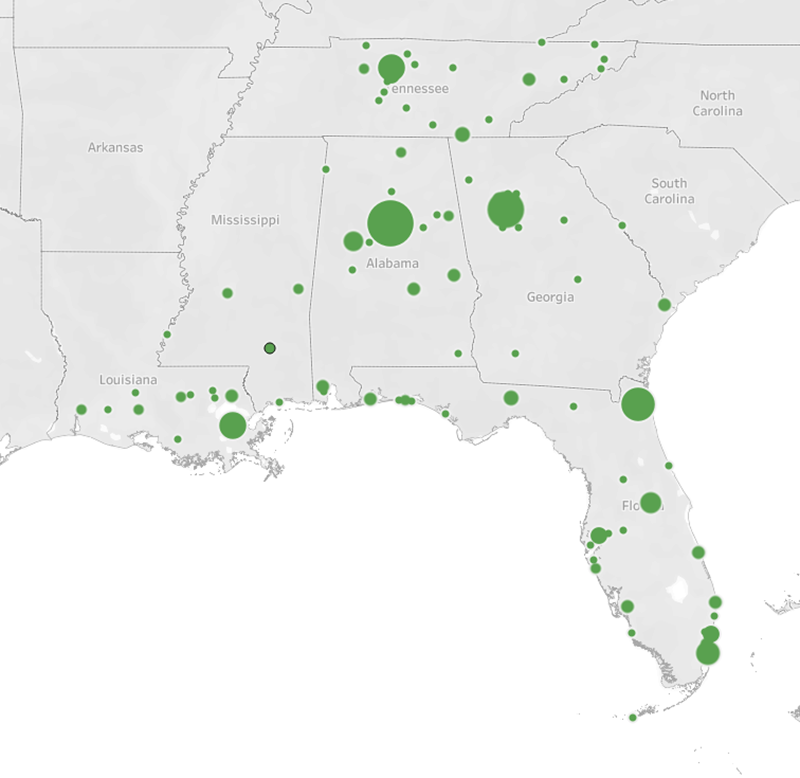

Those are the headline findings from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta's latest round of conversations with business executives and other community leaders across the Reserve Bank's six-state district. Since July, interviews with nearly 300 contacts by the Atlanta Fed's Regional Economic Information Network (REIN) team also found uncertainty remains widespread about the trajectory of the virus and the localized impact on business (see the map indicating concentrations of REIN interviews). Recent results from the Survey of Business Uncertainty, described in this Atlanta Fed macroblog post, reiterate the persistence of this outlook among firms.

REIN team members' in-depth conversations are critical for numerous reasons, especially now. For one, checking in with the same large group throughout the public health crisis offers an evolving, real-time view of business conditions. Ongoing dialogue allowed the REIN staff to better understand the vast uncertainties that compelled many southeastern businesses. Ultimately, these conversations inform monetary policymaking, as grassroots intelligence from REIN helps Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic try to determine how and when the broad macroeconomy will recover.

Atlanta Fed president

Raphael Bostic.

Photo by David Fine

In a July Economy Matters article, a REIN analysis of firms' experiences and expectations pointed to emerging bright spots shadowed by uncertainty. Since then, REIN staff have monitored the sputtering recovery and the forces shaping it, including the expiration of some Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act economic assistance, as well as plans for school reopening.

Growing divergence in pandemic experience

Market demand has varied greatly across industries during the pandemic. Thriving sectors include makers and sellers of home and outdoor products and goods aimed at addressing health and safety concerns. Reports suggest that many prospering retailers have built on years-long trends of consumer preferences for strong, easy-to-use ecommerce platforms and other practices that engender customer loyalty. Residential real estate also remains strong, as homebuilders, real estate agents, and lenders all describe vibrant conditions across the Southeast.

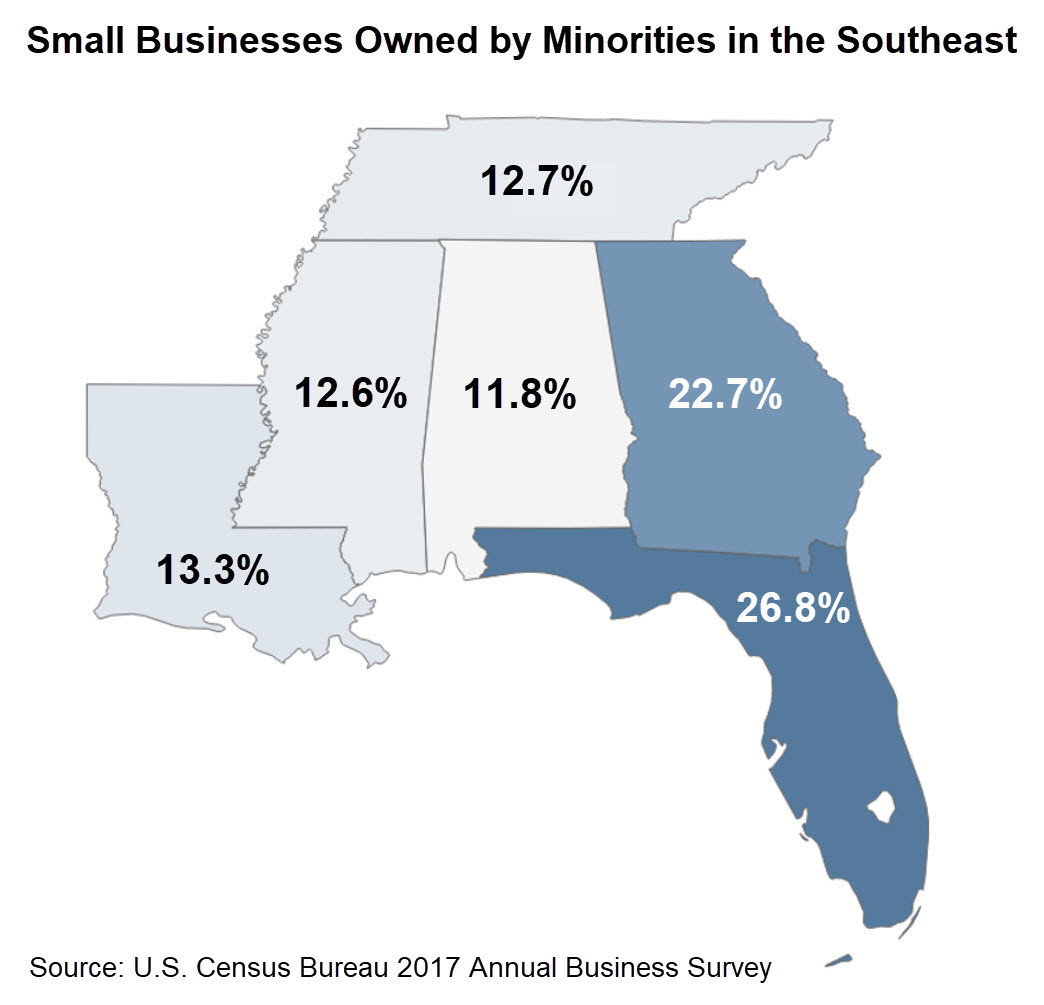

At the same time, many small businesses are struggling, especially where the economic downturn has hit hardest. Recent reports from business leaders suggest the gap separating pandemic business winners and losers may be widening. Key players in the Southeastern small business ecosystem—including chambers of commerce, nonprofits, lenders, and researchers—have voiced deep concerns about the disproportionate effects of the pandemic on small firms and minority-owned businesses, compounding existing disparities in economic opportunity and mobility (see the map). The problem is depicted by Atlanta Fed Community and Economic Development staff here.

The crisis is also affecting individuals and families differently. Like other economic slumps, the pandemic slowdown appears to be widening disparities across income groups. Businesses with high-income customers report little impact on those consumers, even as many low-income people struggle.

“Usually, recessions impact the middle class the most, but this time around, it was lower-income, essential workers that got hit the most,” Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic recently told the Florida Philanthropic Network. “And it has also had a tremendous impact on small businesses and specific sectors."

Broad national statistics sometimes mask uneven fortunes. In fact, after bottoming out in April, overall consumer spending has steadily increased, according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (see the chart). Many firms figure relief payments through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act supported consumer spending. Although some CARES Act supports expired in July and August, early signals from some companies indicate sales stayed solid in August, suggesting that some recipients of CARES Act assistance still had money to spend even after the relief payments. (August consumption data will be released on October 1.) However, some business leaders worried that spending may not hold up, particularly if the job market for lower-skill positions remains weak.

Labor challenges remain

Indeed, the labor market situation remains complex. Many firms facing weak demand for their goods and services expect to continue layoffs through the rest of the year, while companies in high-demand industries might need to add employees.

This dynamic—certain firms shedding jobs as others hire—reshuffles job openings from struggling industries to prospering sectors. Yet shifting workers to new opportunities will likely not be straightforward. Many businesses reported that the skills of most job seekers do not match those required for the open positions. In fact, research suggests that what economists term a reallocation of resources happened more slowly during recovery from the Great Recession than during past recoveries. This phenomenon probably helps to explain why that recovery was so gradual, and some economists believe it could be happening now.

One big reason the job reshuffling is slow is that it takes a long time for people to learn new skills and switch from jobs in, for instance, commercial real estate or the lodging industry to an occupation involved in telemedicine, as recent research from the Chicago Fed explores.

Workers and employers also face other labor market hurdles. Some employers are bracing for labor shortages as workers stay home with young children or school-age students attending classes virtually. As national research has shown, employers noted this is affecting women most, with higher rates of females than males dropping out of the labor force. Many business leaders said they are devising strategies to deal with anticipated labor shortages: operating with minimal staff, rearranging hours to accommodate unpredictable demand swings, and spreading job responsibilities among current staff.

Tourism sends mixed signals

Like the labor market, one of the region's significant economic engines, the tourism industry, is sending mixed signals. Popular urban tourist destinations haven't rebounded. Atlanta Fed contacts in Miami, Nashville, New Orleans, and Orlando continue to paint a bleak picture as hopes have diminished for a near-term surge in visitors. For cities reliant on tourism, the slowdown in visitors permeates the local economy, presenting challenges for city budgets dependent on tourism-related tax revenue. The lack of visitors also damages small businesses that rely on out-of-town customers.

Meanwhile, business travel has all but stopped, particularly in the large convention and meeting industry. A national organization that markets and promotes trade shows has seen a precipitous drop in the number of events compared to 2019. In contrast, businesses with insight into vacation travel noted that less densely populated locations are still drawing large crowds.

The broad hospitality and leisure sector has hemorrhaged jobs since the onset of the pandemic, and although the pace of layoffs has slowed, industry leaders expect job cuts to continue. Many executives figure business travel will not return to pre-COVID levels, and this trend will remain a drag on the industry. An Atlanta Fed macroblog post based on survey data suggests the same, supporting the REIN anecdotal findings.

Workers relocating may further change composition of Southeast

As the pandemic continues to shape economic activity in various ways, it also is affecting where some people choose to live. There are early signs of population shifts. Some less densely populated areas—including the Florida Panhandle, east Tennessee, and coastal Georgia, which in many cases experienced record tourism over the summer—are seeing surges of people moving in or purchasing second homes for longer stays.

Many of these migrants are high-income earners who can work remotely. A developer of homes costing $500,000 and up along the Florida Gulf Coast noted extraordinarily high interest, particularly from people relocating from the West Coast.

Changing migration patterns cut different ways. Some of the region's once-thriving downtowns, like Birmingham and Miami, are feeling the effects of what many REIN contacts think is likely a temporary flight from urban centers because of widespread remote-work arrangements. Business leaders noted that many core business areas have been largely vacated, some even being described as “ghost towns.” A nonprofit leader in Birmingham noted that the pandemic has abruptly halted years of economic momentum in the city's downtown. And in south Florida, the lack of tourists and downtown office workers has hurt remaining businesses—namely, restaurants and bars, retail, and other small businesses.

As the Southeast's economy continues to push through a period unlike any in recent memory, the only certainty seems to be ongoing uncertainty.