Will Tight Labor Markets Be the New Normal?

David Altig

November 5, 2025

https://doi.org/10.29338/wc2025-02

Download the full text of this paper (1,538 KB)

In December 2021, the Atlanta Fed's Economic Survey Research Center asked a sample of Sixth District businesses the following question: "Looking ahead into 2022, what are the biggest areas of concern?" The number one survey response, cited by 23.1 percent of 168 firms responding, was "labor quality/availability."1

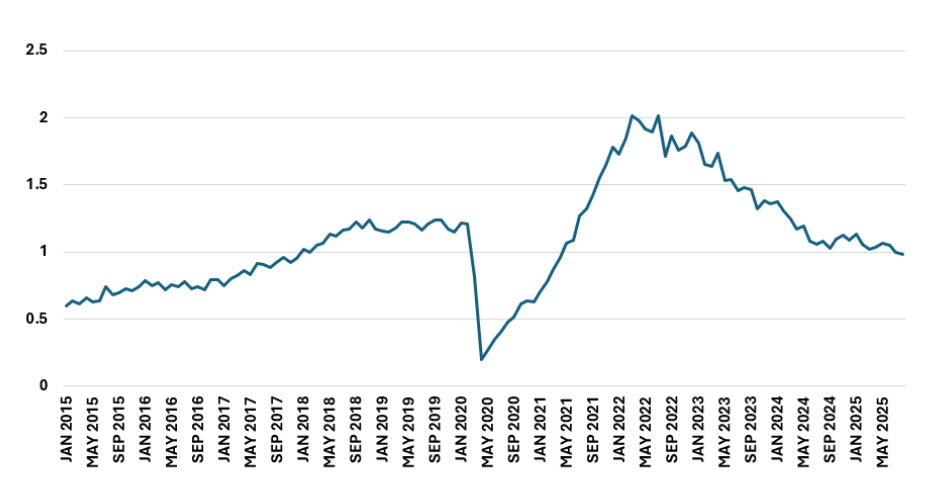

Figure 1 illustrates why labor challenges would have been top of mind for businesses at the time. Job openings (the blue line in the figure) had been sharply increasing since their low point during the pandemic-related shutdown in April 2020 and were in fact very near the peak they would reach in spring 2022. Employee turnover, measured by voluntary quits, matched employer demand patterns, as measured by job openings data. In 2022, both measures reached their highest levels in the (admittedly short) history of the series.

Figure 1: Job Openings and Quits

Thousands

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics; Haver Analytics. Data through August 2025.

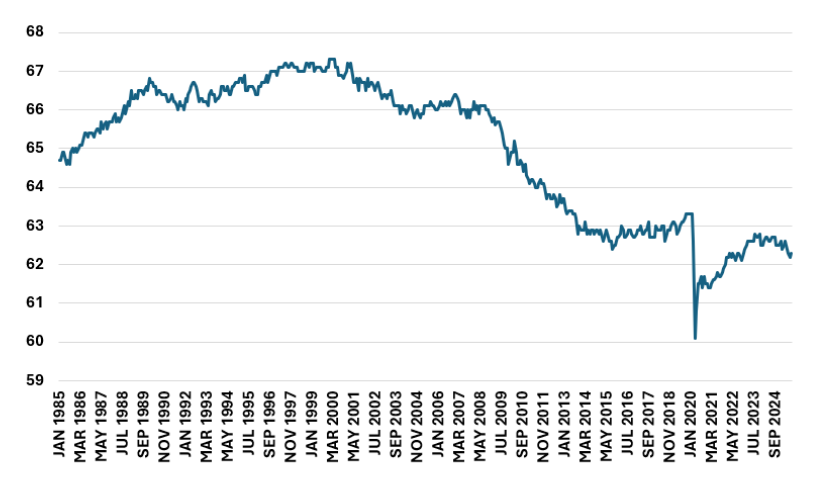

Another, related measure of labor-market tightness—the ratio of job openings to unemployed persons—is shown in figure 2. It is apparent that, at least by this measure, the pressure on employers has significantly diminished over the past several years. As of August this year, there was just under one open job for every unemployed worker, half the number that prevailed in the spring of 2022.

Figure 2: Job Openings per Unemployed Person

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics; Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta; Haver Analytics. Data through August 2025.

It is tempting to conclude that labor-market conditions from mid-2021 through, say 2023, were like so many other phenomena: a pandemic-related aberration. Atlanta Fed economist Andres Blanco, citing recent research he and his co-authors have done, makes the case that the rise in the openings-to-unemployment ratio shown in figure 2 is a result of the inflation surge that began in the latter half of 2021.2 The basic logic is that dollar-wages are slow to adjust to unexpected increases in inflation, which causes inflation-adjusted (or "real") wages to fall. This, in turn, induces employees to increase the intensity with which they seek alternative employment, raising both quits and job openings.

Absent another persistent rise in inflation, or another pandemic with all the specific policies deployed as part of the Covid response, the recent bout of labor-market tightness may in fact prove to be a one-off consequence of a very unusual period. Maybe. But there is also good reason for concern that eventually a re-emergence of labor-market tightness and consequent challenges for employers is likely, due to a different development that is all but inevitable: the expected decline in US population growth and shrinking of the working-age share of the population.

The number of births relative to deaths in the US population has been declining for two decades. According to the latest estimates from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), there is no end to this trend in sight. In the CBO's projections, without immigration flows, the population will begin to shrink by 2034—just a decade from now. Worse, from the perspective of the available labor supply, the population is expected to be increasingly weighted toward age-groups least likely to be labor market participants. The share of the population ages 65 and over, estimated at about 17 percent last year, is expected to rise to about 22 percent by 2040.

Taking births and deaths as a relatively predictable part of the population picture, is a decline in labor supply, and hence pressure on employers in a growing economy, unavoidable? Not necessarily, but if demography is not to become destiny there are essentially four routes to sustaining growth in the US labor supply.

First, immigration can obviously substantially move the population and labor supply, a fact that has been in sharp relief over the past several years. According to the latest estimates from the CBO, the annual growth rate of the US population essentially doubled in the each of the years from 2021 through 2024 relative to the growth rate in 2020.3 About 88 percent of that was accounted for by a surge in net immigration.

Equally notable, changes in immigration enforcement policies are having a major, and uncertain, impact on current labor supply. According to one estimate, net immigration will be negative in 2025.4 The implication of this is that the breakeven rate of job growth could well be zero or even negative.5

The CBO's calculations assume net immigration growth will stabilize at 0.3 percent per annum after the next couple of years, roughly equal to the average rate over the fifteen years prior to the pandemic. While these projections imply a nontrivial offset to declining population growth from net immigration, importing labor comes with complications. Immigration outcomes are driven by multiple competing policy considerations, as the experience of the past half-decade illustrates. Only a fraction of these considerations are economic in nature, and even those that involve economic questions do not always have answers that point in the same direction. All the competing interests, and the tradeoffs involved, are appropriately adjudicated in the political arena—economists have no special claim to expertise in making such judgments.

In any event, even assuming immigration returns to something like the pre-pandemic norm, US population growth is still projected to effectively fall to zero by the mid 2050s. And it should be noted that, in terms of the number of people engaged in global labor market activity, immigration is a zero-sum proposition: a labor-supply gain for one country is a labor-supply loss for another. If the United States has demographic challenges looming, the issue is shared by much of the rest of the world.6

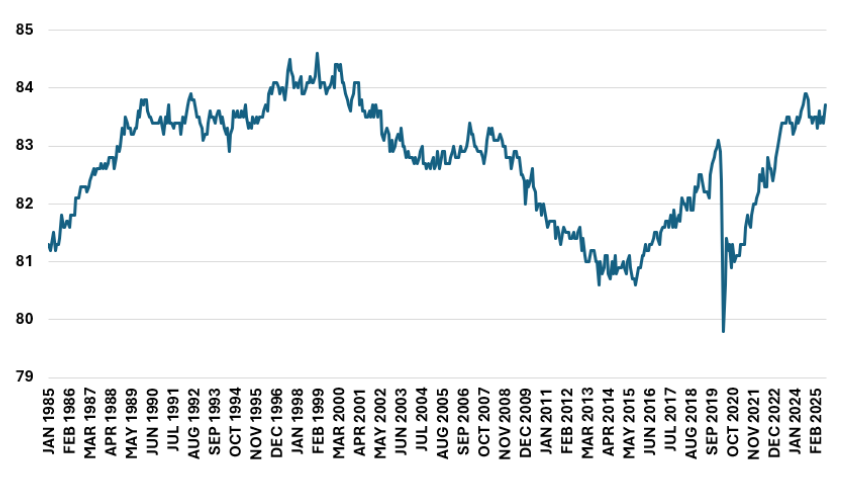

A second, alternative strategy for sustaining, or even growing, the labor supply in the face of declining population growth is to increase the fraction of the population actively participating in the labor market. Here, a first look suggests some promise. Figure 3 charts the labor force participation rate, the fraction of the working-age population that is either employed or actively seeking employment in a given month.

Figure 3: Labor Force Participation Rate: Total (Age 16 Years+)

Percent, seasonally adjusted

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics; Haver Analytics. Data through August 2025.

The participation rate for the entire civilian, non-institutionalized population aged 16 and over has fallen dramatically since its post-WWII peak around the turn of the millennium. Though participation has increased from the low levels of the pandemic years, the rate has been relatively flat over the post-pandemic period (starting roughly in spring 2023) and remains somewhat below the average of the decade preceding the Covid recession. To put a number to these changes, if the participation rate could be returned to 2000 levels the official measure of the labor force would currently be higher by about 1.3 million people as of June this year.

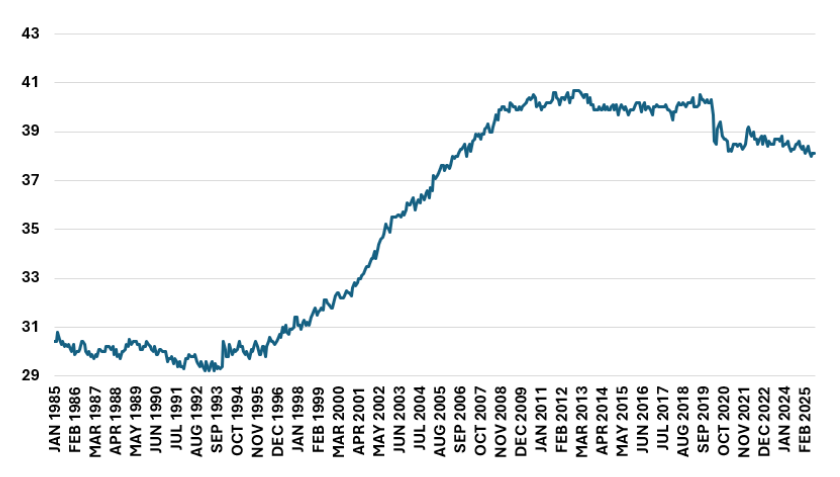

Can bringing individuals who are not in the labor force be part of the answer to declining population growth? Perhaps, but there are some complications. To begin with, the primary cause of declining labor force participation over the past twenty-five years has been the aging of the population. Figure 4 shows the participation rate of so-called prime-age individuals—those 25 to 54 years old. This is the age group with the highest attachment to labor markets. Currently this group's participation rate exceeds pre-pandemic levels. In fact, the share of people in this age-cohort who are either working or actively seeking work is not far from the highest levels seen in the post-WWII era.

Figure 4: Labor Force Participation Rate: 25-54 Years

Percent, seasonally adjusted

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics; Haver Analytics. Data through August 2025.

Obviously, any increase in labor force participation would help to expand the supply of labor. The question is whether this is a viable route to substantially and persistently raising the US labor supply. That question itself raises a couple of other specific questions. One, can those who would normally enter full- or semi-retirement be coaxed into extending their working years? This may be possible. Longer lives and better health into older age certainly increase the feasibility of longer working lives. And in fact, despite having fallen and not recovered since the pandemic, the labor force participation of individuals age 55 and above has increased dramatically since the 1980s, as shown in figure 5.

Figure 5: Labor Force Participation Rate: Ages 55+

Percent, seasonally adjusted

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics; Haver Analytics. Data through August 2025.

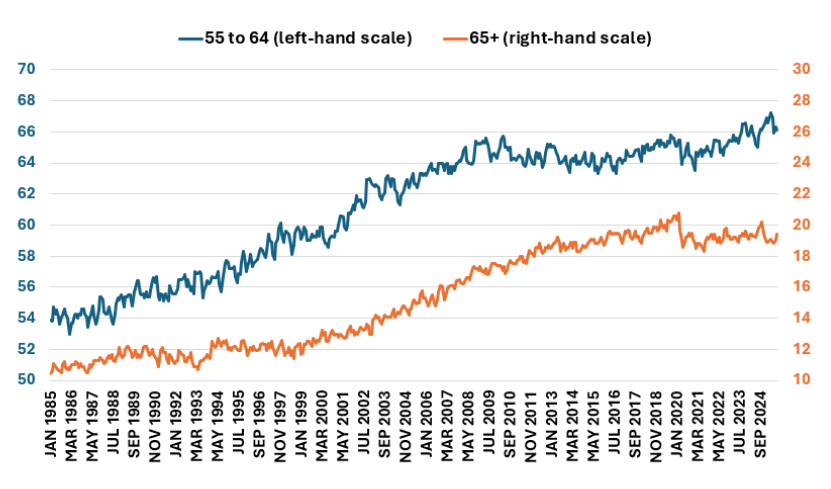

Figure 5, however, buries some important distinctions among the older-than-prime-age group. In figure 6, the 55+ age group is divided into those aged 55-64 and those aged 65 and older. The participation rates for the 55-64 age group have recovered from their pandemic-related lows and now exceed the pre-pandemic level. In this sense, the labor market behavior of this age class appears more like that of prime-age participants. But that is not the case for the rate of the 65+ group, who have not returned to the labor market at the rates seen prior to the Covid-period decline. There is one more important element in figure 6: the participation rates for the older cohorts are dramatically lower than those for younger post-prime-age individuals.

Figure 6: Labor Force Participation Rate: Ages 55 to 64 and 65+

Percent, not seasonally adjusted

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics; Haver Analytics. Data through August 2025.

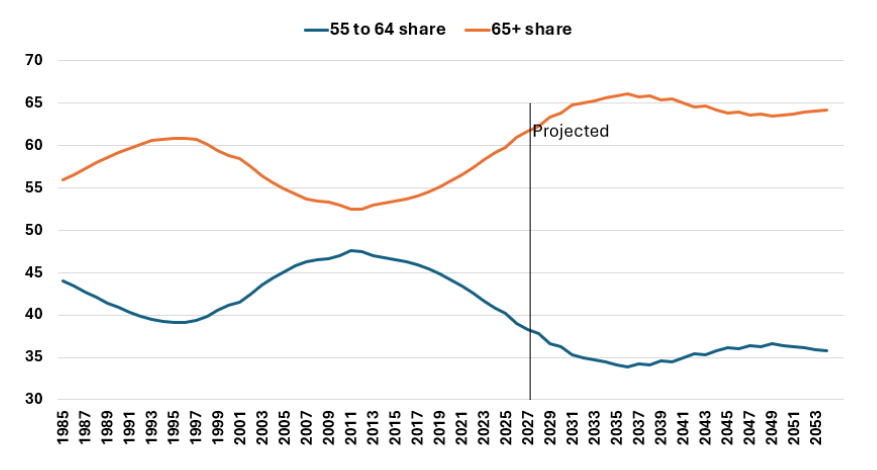

Why this observation is important is revealed in figure 7. While the share of the 55-to-64 age group was increasing relative to the 65+ group until the early 2010s, that trend has since reversed. And, according to CBO projections, the older group will increase in relative size over the next decade and beyond. Thus, growth in the labor supply via increasing participation by potential workers past prime age will increasingly depend on an older group with historically low rates of participation that have exhibited scant growth in the past several years.

Figure 7: Population Shares Within the 55+ Age Group: Actual and Projected

Percent of population ages 55+

Sources: Congressional Budget Office, The Demographic Outlook: 2025 to 2055, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/60875 (through 2024); Congressional Budget Office, An Update to the Demographic Outlook (2025 to 2055), https://www.cbo.gov/publication/61390; author's calculations.

What of the potential to expand the prime-age labor supply? It is worth noting that that prime-age participation in the United States has gone through fairly large and persistent fluctuations over time. There is no doubt that maintaining participation rates near their current levels would help to maintain the available labor supply. However, that would not result in an offset to the negative effects of population developments as much it would simply avoid an amplification of those effects.

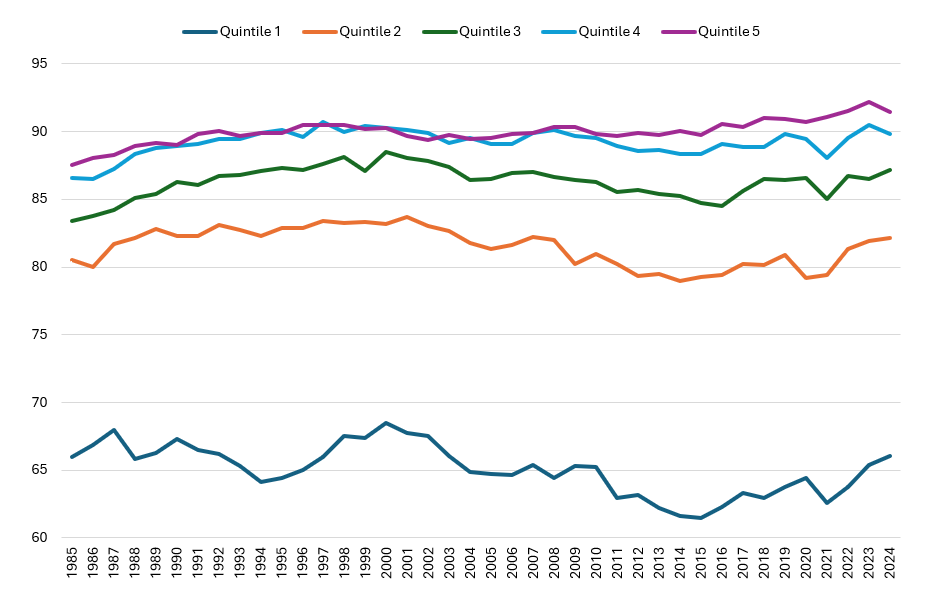

Perhaps, more importantly, the high overall rate of labor market participation among prime-age individuals masks significant differences across the income distribution. Figure 8 plots labor force participation rates for prime-age individuals in different income quintiles for the period from 2010 through 2024. As is clear from this figure, the participation rates for individuals living in households with the lowest income levels are far below those living in higher income households. The reasons for this lie beyond the scope of the present discussion. But there appears to be potential in bringing lower-income individuals into the formal labor market—a topic that will be explored in a follow-up to this article.

Figure 8: Labor Force Participation Rates by Income Quintile

Percent

Note: The data for these series come from March observations in the Census Current Population Survey for each of the relevant years. Quintiles are constructed using household weights from the Annual Social and Economic Supplements.

Sources: US Census Bureau: Current Population Survey and Annual Social and Economic Supplements; author’s calculations.

Nonetheless, there are clear limitations on the degree to which increasing labor force participation can overcome the challenge of declining population growth. Participation rates cannot increase without bound. After all, 100 percent is the physical limit on participation, and the realistic limit is likely far short of that number.

If solutions appealing to immigration and participation rates have limitations, is there another avenue for increasing the labor supply that does not rely on expanding the number of active participants in the labor market? Yes. For one, in the broadest (and most economically accurate) sense, labor supply should be thought of in terms of hours of work supplied, not the number of people supplying them. Expanding the average number hours worked per person obviously implies an expansion of the labor supply. But even leaving aside the fact that average hours worked decline as wealth increases, like participation rates, hours per person can only grow so much. There are only twenty-four hours in a day and the biological capacity for work is well short of that.

Fortunately, there is a fourth way to meet the labor needs of employers and support economic growth, even as growth in the number of bodies in the labor force stagnates: increasing the effective labor supply. "Effective" in this case refers to the productive capacity of each worker in the labor force. Hence, the key to sustainably expanding effective labor supply in the face of declining numbers of workers or work hours is productivity growth. Here the road leads to workforce development in all its manifestations—primary and secondary educational curricula, public workforce institutions and infrastructure, and private-employer organizational development programs and strategies.

These days productivity discussions naturally gravitate toward the broad class of technological advances typically bundled under the label "artificial intelligence," commonly referred to by the simple acronym AI. It's early days for AI. In an analysis conducted by the Atlanta Fed, Sergio Galeano, Nye Hodge, and Alex Ruder document the growing, but still small, percentage of jobs requiring AI skills.7 Because the penetration of AI is still emerging, there is no difficulty in finding an expert to support most opinions about the potential for the technology to supercharge productivity growth, its impact on the work and the labor force, and the horizon over which all of it matters—whatever those opinions might be.

For present purposes, there are two simple points directly related to the topic of this article. First, technology adoption can be a solution to labor shortages. But, if AI proves to be a truly transformative technology, and if the history of this episode at least rhymes with past innovation revolutions, labor will again be integral to unleashing the technology's full potential.

Another way to say this is that the productive potential of AI is not independent of the choices made by both private and public sectors, including those related to labor supply. As has been the case with the arrival of all past disruptive technologies, AI's potential will almost certainly and critically depend on the scale and nature of investments in physical capital, organizational capital, and importantly human capital.8 AI may partially solve looming challenges in labor availability, but its full promise lies in making choices that maximize the quality of work, for both employers and employees, in all its dimensions.

A second point is that a program of improving the productivity of labor is even more important if advances like AI prove insufficient in themselves to overcome the population-related drag on labor supply. Whether an AI optimist or an AI skeptic, there is a strong case for substantial investments in workforce development.

The reality of declining population growth and an increasingly aging population very likely means that labor scarcity will significantly restrain economic growth absent the ability to expand the effective labor supply. An active strategy to meet this challenge requires investments in worker skills, removing disincentives for workers to pursue the attainment of those skills, and enhancing the employment proposition for workers (which includes, but goes well beyond, wages alone). As the population projections noted here make clear, the timeframe for meeting the challenge is short.

By David Altig, executive vice president and chief economic adviser.

Please send comments to Dave.Altig@atl.frb.org.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta's Community and Economic Development function supports the Central Bank's mandate of stable prices and maximum employment by helping improve the economic opportunity of low- and moderate-income (LMI) individuals and underserved places for a stronger economy for all Americans. Community development is one of the Federal Reserve's core functions and this responsibility is rooted in its mandates from Congress. Our Workforce Currents series addresses emerging and critical issues in workforce development. Find more research, use data tools, and sign up for email updates at atlantafed.org/commdev. The views expressed here are the author's and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta or the Federal Reserve System. Any remaining errors are the author's responsibility.

1 For comparison, the second most popular response was "cost pressures/inflation," chosen by 13.1 percent of respondents. Click here for full survey results.

2 Andres Blanco, "Labor Market Dynamics During the 2021-24 Inflation Surge," Policy Hub 2025-3 (Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, June 2025).

3 Congressional Budget Office, "An Update to the Demographic Outlook, 2025 to 2055" (September 10, 2025).

4 Wendy Edelberg, Stan Veuger, and Tara Watson, "Immigration Policy and Its Macroeconomic Effects in the Second Trump Administration," AEI Economic Perspectives (July 2, 2025).

5 "Breakeven" refers to the number of net jobs needed to keep the unemployment rate constant.

6 See, for example, this report from the United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, "World Populations Prospects 2024".

7 Sergio Galeano, Nyerere Hodge, and Alexander Ruder, "By Degree(s): Measuring Employer Demand for AI Skills by Educational Requirements," Workforce Currents 2025-01 (Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, May 21, 2025).

8 On this, see Martin Fleming's recent, extensive study of AI and what lessons can be gleaned from prior technological revolutions.