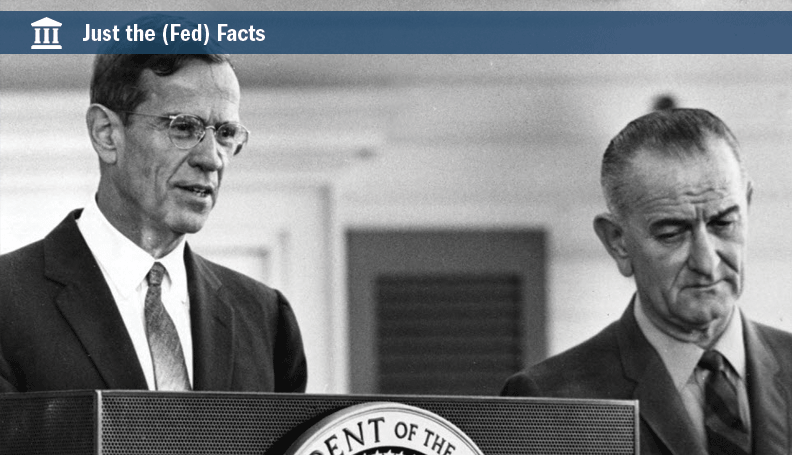

Fed Chair William McChesney Martin and President Lyndon Johnson

Fed Chair William McChesney Martin and President Lyndon JohnsonAssociated Press

Editor's note: This article is also available in Spanish and Portuguese.

For the Federal Reserve, taking unpopular measures is sometimes part of the job. In some ways, it is the job.

William McChesney Martin, Fed chairman from 1951 to 1970, famously described the Fed's role as "to take away the punch bowl just as the party gets going." Martin's point was serious. To contain inflation and minimize the risk of future economic damage, the Fed must be free to tighten monetary policy, by raising interest rates or taking other actions, just as the economy peaks.

Tightening policy is often politically unpopular. Many Fed chairs, including Martin, Paul Volcker, and Alan Greenspan, were criticized by presidents who preferred that economic expansions continue unfettered by tighter monetary policy, regardless of long-term consequences. Presidents have even called for lower interest rates in the State of the Union address.

But the Fed strives to be apolitical. Research on central bank independence—a field of study that came into its own in the late 1980s—overwhelmingly shows that monetary policy is most effective when it is shaped free from the influence of short-term political pressures that may not be in the long-term best interest of the economy.

This need for an apolitical central bank is why the Fed is structured as it is. Members of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, who always vote on the policy-setting Federal Open Market Committee, are appointed to 14-year terms. These terms span several U.S. presidential administrations, ensuring that policymakers do not have an incentive to skew monetary policy to ensure their reappointment every four years.

In addition, Federal Reserve Bank presidents are hired outside the political arena. Reserve Bank boards of directors—excluding board members who are bankers—select presidents. The boards' selections must be approved by the Fed Board of Governors but not by congressional representatives.

Over the long term, the aim of central bankers and elected officials is a healthy U.S. economy. "At the end of the day, both political people and political groups and the Federal Reserve want the same thing for the country," former Atlanta Fed President Dennis Lockhart recently told the Wall Street Journal.

Balancing independence and accountability

In 1978, Congress established the Fed's modern objectives of low and stable inflation and maximum employment, while balancing Fed accountability with political independence. While the Fed's operations are audited extensively, monetary policymaking is not subject to immediate congressional review. Neither the president nor Congress has to approve monetary policy decisions.

This legislation also strengthened the central bank's accountability and transparency. The Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act of 1978 requires the Federal Reserve Board to report to Congress twice a year about plans to meet its dual objectives. A key venue for reviewing the Fed's approach is the twice-yearly testimony of the chair, along with the associated Monetary Policy Report.

As Fed Vice Chair Stanley Fischer has noted, accountability to elected officials and the public "is an essential complement to central bank independence." The accountability requirements have been largely unchanged since the late 1970s, but the Fed has significantly expanded its public communications. A few examples:

- The Federal Open Market Committee began issuing post-meeting statements in 1994, and in 2002 began listing how each member voted.

- In 2005, the Committee started releasing meeting minutes three weeks after each meeting, several weeks sooner than it had previously released them.

- Two years later, FOMC members began releasing their individual projections for the economy and the federal funds rate.

- In 2011, Chair Ben Bernanke initiated quarterly press conferences after FOMC sessions, which continue to this day.

So the Fed strives to conduct business apolitically. At the same time, it is a public institution accountable to the people and their elected representatives, and one working amid a changing economy and financial system. For example, since the financial crisis and Great Recession, the Fed has been tasked with increased responsibility for financial system stability.

The Fed has established a tradition of acting in ways it judges best for the long-term health of the nation's economy, often despite political pressures. The Volcker-led Fed of the 1980s subdued runaway inflation by tightening monetary policy in the face of intense opposition. That policy regime has since been praised.

More recently, the Fed took actions during and after the financial crisis that drew considerable criticism, including emergency lending facilities and large-scale asset purchases that helped to keep the financial system stable and stimulate economic growth. Numerous critics charged that the Fed's actions would spark inflation. Damaging inflation, however, has not materialized. In fact, many observers inside and outside the Fed view the central bank's actions as instrumental in helping the nation avert an even worse economic recession than the one we endured.